Warren G. Harding Was The First Celebrity-Endorsed President

Warren G. Harding campaigns for the presidency in 1919. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Nearly a century after his death, Warren G. Harding is having a moment in the limelight.

Thanks to timeless curiosity and modern genetic testing, the New York Times recently broke the very old news that Harding fathered a love child with Nan Britton while in the Senate. (This comes on the heels of the Library of Congress’s release of sheafs of salacious letters between Harding and Carrie Phillips, another woman with whom he had an extramarital relationship.)

Meanwhile, President Obama’s environmentally-minded trip to Alaska this week has stirred up memories of Harding’s own northern tour, during which the Navy shelled the Taku Glacier to make an avalanche for Harding’s amusement.

Some, such as Harding biography authors Ronald and Allis Radosh, are taking this opportunity to try to resuscitate Harding’s less-than-stellar reputation, which has left him languishing at the bottom of most ranked presidential lists, fighting James Buchanan for the next-to-worst spot. They point out that Harding, despite the scandals that rocked his presidency, was ahead of his time on social issues, and even managed to balance the budget.

But there is another good reason to revisit Harding. As the 2016 presidential race creeps up, and celebrities begin throwing their megaphoned voices behind various candidates, it’s worth remembering that Warren G. Harding didn’t just fill a chair for two years—he invented what has become a national specialty: the presidential celebrity endorsement.

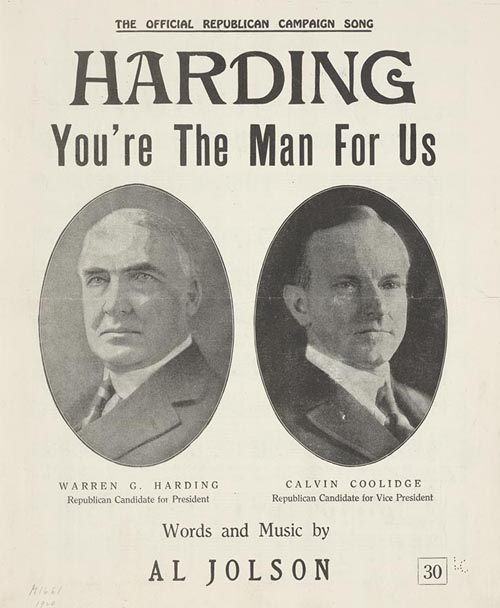

Sheet music for stage and screen star Al Jolson’s pro-Harding campaign song. (Image: Library of Congress)

In the runup to the 1920 Presidential election, Harding was a fifth-year Republican senator from Ohio with a decent reputation and without much to set him apart. The New York Times called him “a very respectable Ohio politician of the second class,” and referred to his Senate record as “faint and colorless”. Harding likely would have stayed that way but for the unexpected death of Teddy Roosevelt at the beginning of 1919. Roosevelt was a shoo-in for his party’s presidential nomination, and with the heavyweight out of the picture, dozens of greener Republicans, Harding among them, found themselves with a fighting chance at the presidency.

Harding didn’t do much to distinguish himself during the primary, content to toe the party line and make long speeches about nothing—a tactic he called “bloviation.” In the meantime, the frontrunners slowly reduced their own chances until, late in the last night of the Republican Convention, the delegates started looking into the pack of dark horses for a more suitable candidate. According to historian Wesley M. Bagby, Harding “was more acceptable than the others because he had not spent large sums,” and after over a dozen rounds of ballot-casting, all of which ended in deadlock, “a kind of weary understanding was reached… that support in the morning would be thrown to Harding.” And so the bloviating, colorless Senator found himself gunning for the presidency.

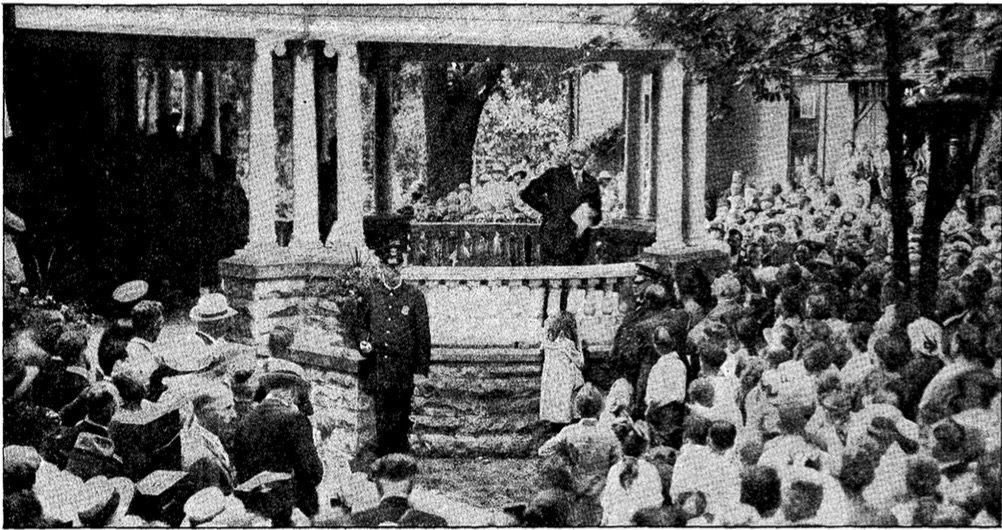

Harding accepts the Republican nomination from his front porch. (Photo: Underwood & Underwood/Public Domain)

Harding had a particular strategy in mind for the real race. While the Democratic ticket, made up of James M. Cox and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, hit the campaign trail, Harding decided to run a “front porch campaign”—rather than heading out to win over the world, he’d bring the world to his own front door in Marion, Ohio, where he could better control the message. Several past presidents, including James A. Garfield and Benjamin Harrison, had tried this technique, but William McKinley had perfected it, winning the 1896 election by bringing nearly a million supporters to his house over the course of the campaign and greeting them with carefully constructed media events.

Harding’s front porch. When he was campaigning in 1920, the whole place would be mobbed. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Fortunately, Harding had recently remodeled his front porch to look almost exactly like McKinley’s, with stately columns and a rotunda that looked almost like a stage. To complete the transformation, the GOP Executive Committee moved McKinley’s flagpole to Harding’s lawn. The infrastructure in place, Harding, his wife Florence Kling, and his savviest adviser, advertising veteran Albert Lasker, quickly built a public relations machine to match. Soon every day was a carefully organized parade of photo ops, carefully calibrated speeches, and press conferences, all packaged perfectly and sent to the papers and newsreels. Those who couldn’t come to Ohio to meet Harding got to know him on the page and on the screen.

Florence was instrumental in getting Harding to the White House—legend has it that when he tried to call in his resignation during the Republican primary, she grabbed the phone out of his hand. She had her ear to the ground in Marion, and whenever a luminary (or someone who knew someone who knew a luminary) was coming through, she grabbed them and brought them to the porch.

Florence Kling Harding, a shrewd campaigner. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Her biggest coup was Al Jolson. Jolson, who would later become famous as the first person to ever speak in a movie, was the biggest star in America in the 1920s, all over Broadway and creeping into movies. A critic at the time called him “the concentration of our national health and gaiety,” and some consider him the first rock star—onstage, he was charismatic and melodramatic, with a tendency to run all over the stage singing directly to audience members, sweat pouring off his face. Offstage, he happened to be a staunch Republican, and on August 24th, 1920, Jolson, his charisma, and 70 of his fellow actors got on trains and rode from Chicago and New York to Ohio. With the help of a jazzy marching band, they paraded down the street from the station to Harding’s house (the campaign had renamed it Victory Way, and decked it with cardboard arches), singing, chanting, and leading a growing trail of “Harding supporters, visitors, Marionites, and starstruck movie fans.”

Jolson climbed onto the porch and declared himself the president of the “Harding-Coolidge Theatrical League,” and Florence pinned a flower to Jolson’s lapel. Harding then stepped forward for his speech, during which he waxed political about actors and plays that he loved, including Shakespeare’s “Charles the Fifth” [sic], in which the king walks among his soldiers to learn their concerns—just as he, Harding, had learned the concerns of U.S. citizens by standing on his porch. The whole contingent capped things off by singing “Harding You’re The Man For Us,” which Jolson had written quickly for the occasion, possibly while on the train, and which called Harding “a man who’ll make the White House/Shine out just like a lighthouse” rather than citing any concrete political positions or relevant issues. (Jolson’s song for the 1924 campaign, “Keep Cool and Keep Coolidge,” was slightly better.)

Harding, Lasker and Florence got 600,000 people to the porch over the course of the campaign, and a decent number of them were famous—the Chicago Cubs came, as did actors Douglas Fairbanks, Lillian Gish, Pearl White, and Mary Pickford. Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Harvey Firestone were too busy to make the trek, but lent their support from afar. Lillian Russell, an opera-turned-screen-star and a self-described “born Republican” who recruited for the Marine Corps during the war, lent her stumping skills to Harding during his campaign. “The booking agent who arranged the tour of three-and-one-half weeks gave me a grasshopper’s life, jumping from city to city” she wrote later in Cosmopolitan. “I made three or four speeches a day in 15 states.” Meanwhile, if Harding needed to, he’d do it right from Marion—like the time he threw the first pitch out at a local baseball game, then turned to the cameras, still suited up in a Cubs uniform, and talked about how the Democrats weren’t good team players.

Today, all of these events are considered “advertising triumphs,” presaging the endless parade of endorsements we can now expect during American elections at pretty much every level, from high school cabinet races to years-long Presidential ones. At the time, they were, above all, effective. Harding went from being the least-bad nominee, wearily chosen after a night full of deadlocks, to grabbing the largest slice of the popular vote in history: 60.3 percent to James Cox’s 34.1 percent. His popularity remained sky-high throughout his time in office. And if today we don’t remember anything he did there—if, indeed, it might not fill out a Jolson-length campaign song—all the more reason to remember how he got there in the first place.

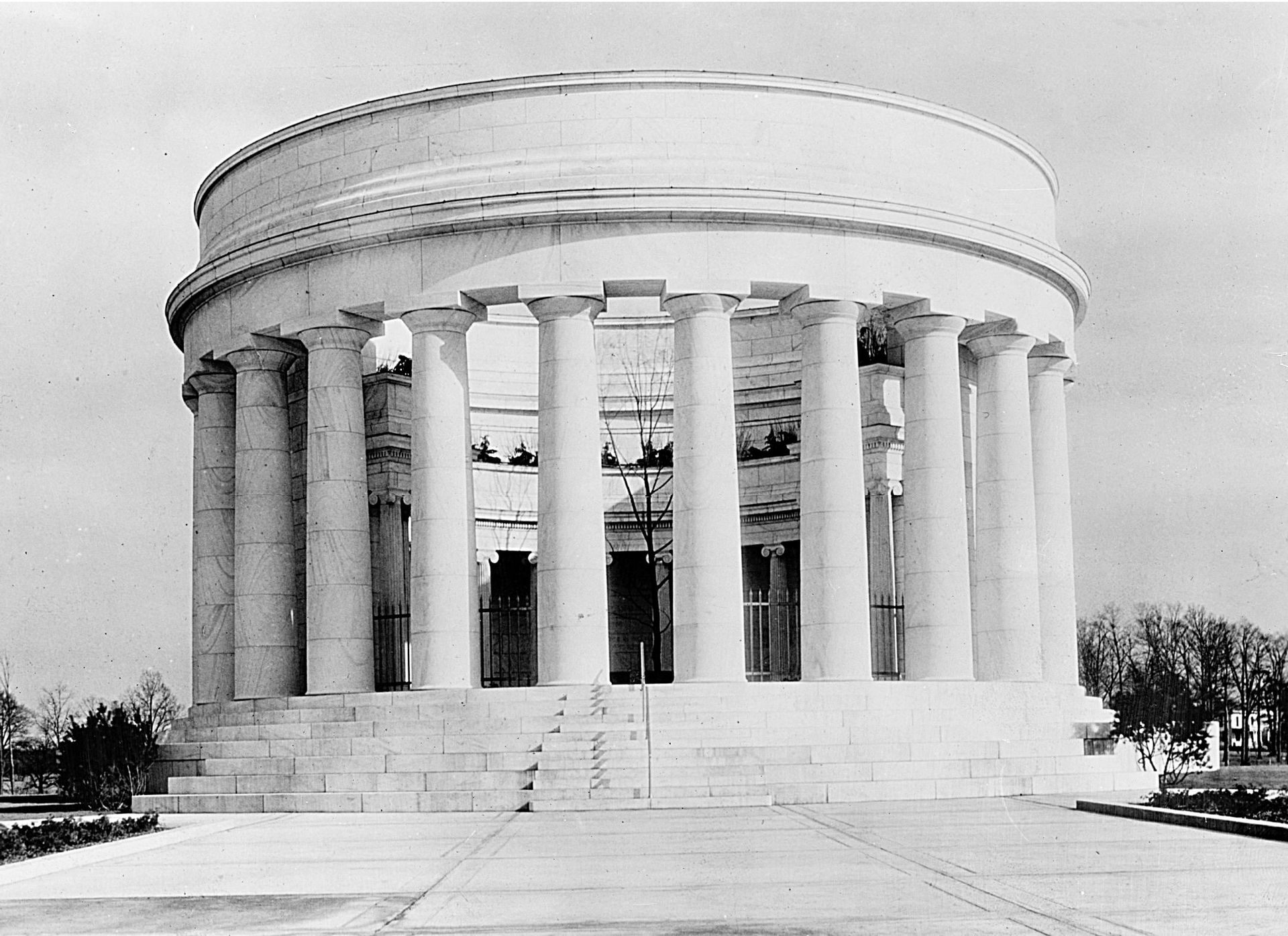

Harding’s tomb, also in Marion, Ohio, looks suspiciously like his front porch. (Image: Library of Congress)

Update, 9/3: The original version of this article said that Harding “didn’t just fill a chair for four years”—he actually filled that chair for only two years before dying in office. Harding was also a fifth-year senator in his first term, not a three-term senator. Thanks to James O’Rourke and Benjamin Brown for the corrections, and we regret the errors.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook