What to Wear in the Arctic: Striking Photos of Traditional Footwear

Napaskiak, Alaska, 1989. (All Photos: © 2016 Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto, Canada/Ron Wood)

How do you dress for the Arctic? The world’s northernmost region is incompatible with farming, frequently blanketed with snow, and home to long winters with barely a hint of daylight. However, it’s estimated that the area around the North Pole has been inhabited for some 40,000 years. Settling so far north would never have been possible if the 40 ethnic groups that live there today had not figured out ingenious methods of braving the cold, particularly through hardy clothing and shoes.

The footwear and garments produced by the Arctic’s indigenous populations has long been an area of interest for Toronto’s Bata Shoe Museum. From the 1970s to the 1990s, the Museum supported trips to the Arctic to seek first-hand knowledge of how clothing and footwear is produced and worn, and how it reflects local culture.

The boots in the above photograph, for example, were made by a Yup’ik seamstress in Napaskiak, Alaska. “Traditionally, beautiful boots were worn by hunters to show their respect to the animal spirits,” the museum explains. These embellished boots, now worn on special occasions, are made from bear, spotted seal, bearded seal, wolverine and calf skin.

The Yup’ik boots are just one example from the Bata Shoe Museum’s new exhibition of traditional Arctic footwear. This exhibition showcases rare examples of shoes, clothing and tools, all of which display the artistry, skill, and innovation that goes into creating attire capable of helping humans live in one of the most inhospitable climates on earth.

Greenland, 19th Century.

According to the Museum, “This tall women’s boot was collected from an unknown source in 1903. This artifact is very similar to contemporary examples of Greenlandic footwear in both their materials and construction, showing a continuity of style over the last century.”

Nuuk, Greenland, 1955.

“Gender is, in part, expressed through footwear design in traditional Greenlandic dress. Men wear boots that typically reach only as high as the mid‐calf while women’s soar thigh‐high. Colour is also a feature of gender differentiation: white and red are commonly used for women’s footwear while black is reserved for men. This pair of red kamiit were made by Laurie Jeremiassen for her silver wedding anniversary in 1955.”

Kablunangajuit, Labrador, Canada, 1880s.

“The distinctive smock‐like pleating found on these kamiit, commonly called kamiks, is characteristic of Kablunangajuit work from the southern part of Labrador, in Canada. The pleating of sealskin requires great skill and provided proof of a seamstress’s proficiency. The distinctive color of these boots comes from being dyed with alder bark, which increases the water repellent capabilities of sealskin boots.”

Coral Harbour, Nunavut, Canada, 1987.

“Inuit women in Canada innovated sophisticated boot making and tailoring techniques to shape skin footwear and clothing. For the coldest weather, inner and outer boots were layered in ways which made the most use of the insulating qualities of the skins. At the same time, these boot layers could be adjusted or removed in a way that allowed the build‐up of heat and moisture to be regulated. This boot features boot liners of baby seal and caribou worn under inner slippers of furred seal, as well as sealskin outer boots.”

Arctic Bay, Nunavut, Canada, 1987.

“Fur inlay is a technique used by Inuit seamstresses to create highly intricate designs. Traditional patterns are geometric while more contemporary boots feature highly curvilinear motifs, such as animals or floral patterns. A difficult challenge when creating this type of decoration is matching the nap of the different furs used to create the design so that all the hairs lie in the same direction.”

Nunapitchuk, Baird Inlet, Alaska, 1992.

“When creating waterproof footwear, Alaskan women displayed great cleverness in their choice of materials. This boot is made with salmon skin and was tanned using urine, which helps stabilize the skin and ensure its impermeability. Salmon skin boots are lightweight and waterproof and were often worn with grass or textile liners for added warmth. This boot is part of a pair made by Nunamiut seamstress Eliza Chase in 1992.”

Orlofka, Eastern Siberia, Russia, 1960s.

“Historically, trade networks provided the Even, Evenki and Koryak with access to colourful beads, which they have used to skillfully decorate their clothing and footwear for centuries. This beaded reindeer skin boot was made by Demyanskaya Ekaterina Geracetovna in the 1960s.”

Antipayota, Siberia, Russia, early 1990s.

“Among the Nenet, gender identity is sewn into the boots that they wear. Women’s boots often feature triangular inserts at the ankle, that when read from the wearer’s point of view resemble a chum, or conical tent, representing Nenet homes. A line of red textile runs toward the toe to symbolize a women’s responsibility to keep the hearth fire burning. This pair of woman’s boots was made by Nenet seamstress Veka Khydi in the early 1990s.”

Mansi, Beloyarsk, Ob Basin, Western Siberia, Russia, 1980s.

“Garments and boots made of white reindeer fur are prized and only individuals with large reindeer herds can afford to kill enough animals to supply the desired white skins needed for a particular garment. This pair of all‐white reindeer boots was made by Natasha Moldanova in the 1980s for her son, a hunter and fisherman named Valery. She used coloured strips of wool to highlight the seams of the boot as well as to make the stripe just under the knee that identifies the wearer as male. The boots are held tight to the leg by handwoven garters with wool pompoms. Boots like these were worn to the annual reindeer festival held in March.”

Rysriny Settlement, Surgut District, Siberia, Russia.

“The designs used to embellish clothing and footwear in Western Siberia often refer to ideas of home or reflect aspects of the natural world around them. The geometric designs used by the Khanty reference the wide variety of wildlife important to them, from moose and reindeer to bears and rabbits. This pair of mid‐century women’s boots features a repeated pattern of alder‐dyed skin that may reference animal tracks. The repetition of pattern is meant to communicate the idea of fertility to the spirit world, bringing more animals to the Khanty.”

Purnu, Sweden, 1967.

“Although coastal Sami relied on marine life for their livelihoods, reindeer skin was preferred over seal and fish skin when making clothing and footwear. This pair of reindeer skin boots are Karesuando Sami and like the other pairs, was made from dehaired reindeer dyed with alder bark to increase their impermeability.”

Aiddejavre, Norway.

“Boots across Sápmi share a number of common features, from the use of colourful textiles to the distinctive upturned toe. However, regional differences are also present. The different colours and patterns found in the long ties, called vuoddagat, reflect regional differences. The construction details also reveal where boots were made.”

Vuotso, Finland, mid‐20th century.

“Many Sami boots feature soles that are made of two or more pieces of reindeer skin. These pieces are sewn together so that the nap of the fur faces opposite directions, increasing the sole’s traction. This pair was made by a Finnish Sami seamstress in the mid‐20th century.”

Krasneno, Siberia, Russia, late 1980s.

“Among the Even, Evenski and Chukchi, boot makers crafted innovative soles that allowed for better traction when walking across slippery ice and snow. Using the skins found between the toes on a reindeer’s foot, seamstresses created boots with thick, furry soles which had the reindeer hairs splayed out in every direction. This additional traction was not only useful when walking or running across ice, it also helped to secure skis to boots. This pair dates to the late 1980s. The pieced sole and reindeer toe‐skins were also collected around the same time.”

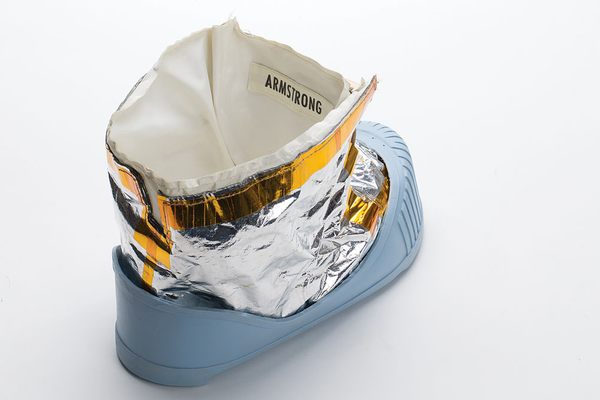

Point Hope, Alaska, 19th century.

“Ulus are curved knives used to cut skins and remove any fat. The shape of the blade, handle and stem is distinct to each woman and region. Like all women’s tools in the Arctic, ulus were made by men for women to use. Ulus were prized possessions and seamstresses were often buried with them. This Inupiat ivory‐handled ulu comes from Point Hope, Alaska.”

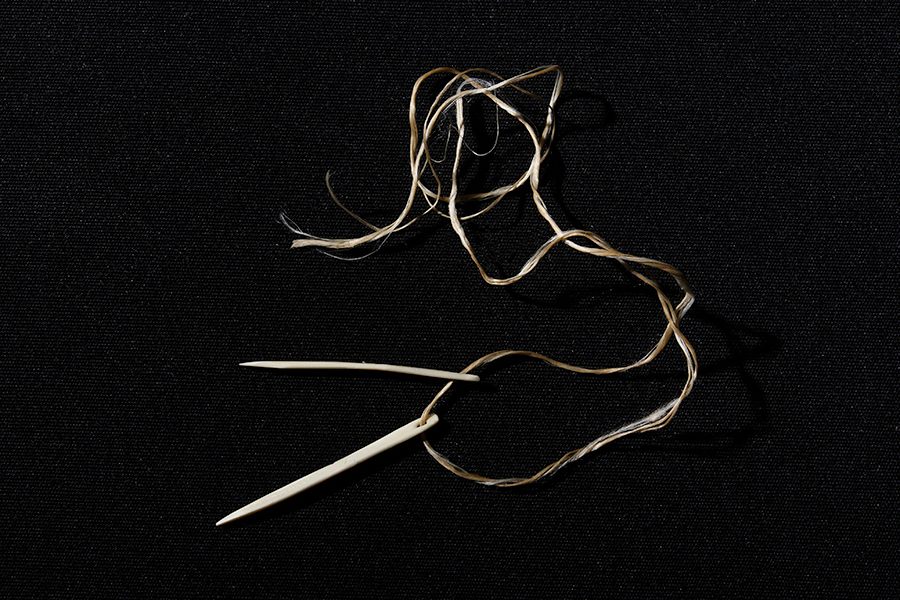

Sanikiluaq, Belcher Island, Nunavut, Canada, 1980s.

“Before the introduction of steel needles, Arctic seamstresses used needles made of bird bone. These Ungava Inuit needles were crafted from the wing bones of an eider duck. They are threaded with sinew, which is dried tendon used as thread. These needles were made by Sam Willie Iqaluk in the 1980s.”

Sweden, 1990s.

“Delicate bird bone needles were stored in special cases across the Arctic region. These cases come in a wide variety of styles and are often works of art in their own right. Decorative cylinders crafted out of ivory are common in Alaska. This example of a Soppero‐ Karesuando Sami chatelaine features a cylindrical needle case made from reindeer antler. This piece was made by Thomas Marainen in the late 1990s. Today, chatelaines such as this are worn for special occasions.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook