When America’s Most Notorious Lobbyist Produced a Dolph Lundgren Film

Jack Abramoff and the story of Red Scorpion.

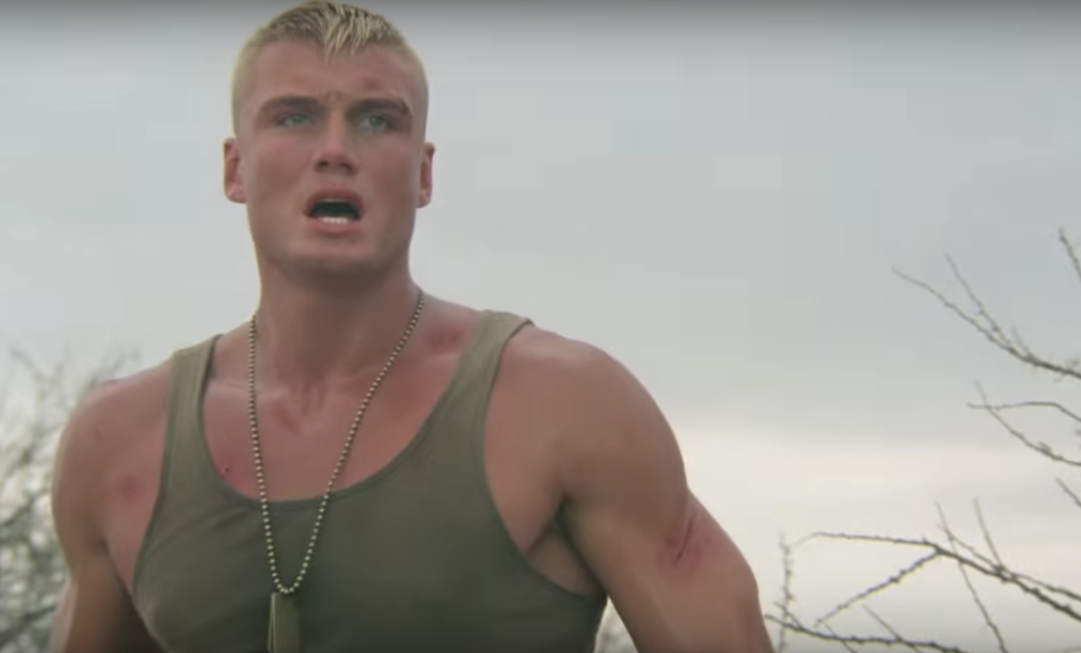

Lundgren in Red Scorpion. (Photo: YouTube)

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

No matter how many redemption tours he goes on, Jack Abramoff remains an infamous name in political circles.

In the mid-2000s, he was the man at the center of a wide array of lobbying scandals, sometimes involving obscure parts of the United States like the Northern Mariana Islands and Guam. A decade ago this month, Abramoff was planning for a prison stay, having just been sentenced in a fraud case involving a casino cruise line. (Hasn’t that happened to you?)

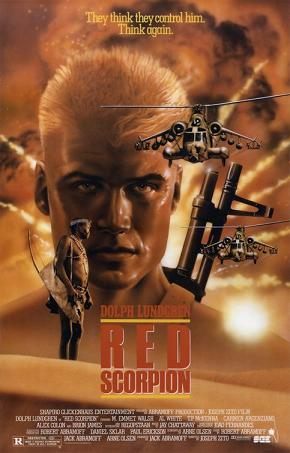

But one part of the Abramoff story that is rarely told is the period of his career where he was a Hollywood film producer. A standout from that period was 1989’s Red Scorpion, starring Dolph Lundgren as a Soviet-trained super killer. Somewhere in between 1980s shlock and 1980s awesomeness, the controversial Red Scorpion has gone on to become a cult classic of sorts. But the story around the film is probably more interesting than the movie itself.

Months before its release in the U.S., Variety savaged Red Scorpion, calling it “a dull, below-average action pic.”

“Joseph Zito’s sluggish direction lingers on nonessentials,” the entertainment news outlet wrote in a 1988 review. “Tediousness could have been alleviated by dropping at least a reel’s worth of trekking across the African desert. Lundgren provides little more than sustained beefcake.”

And compared to the New York Times, Variety was actually nice; Times reviewer Stephen Holden wrote that “the movie’s reflective moments belong to Mr. Lundgren’s sweaty chest.”

The reviews, along with the $4,192,440 Red Scorpion made in its theatrical run, suggested that Jack Abramoff’s film career wouldn’t last too long.

The film—written by Jack, his brother Robert, and Arne Olsen—came after a period when Abramoff had already dabbled in Republican politics, building ties to both Grover Norquist through the College Republicans and the Reagan administration during the Oliver North scandal.

At the time, Abramoff was looking for a career change, and he found it thanks to a movement in late-’80s Hollywood that allowed filmmakers with money and a dream to produce a lot of low-budget action movies that riffed off the Reagan-era Republicanism of the Rambo series. As Abramoff was both a Reagan-era Republican and a guy who grew up in Beverly Hills, he was pretty much the perfect person to take advantage of this B-movie trend.

Jack Abramoff in 2011. (Photo: Madeleine Ball/CC BY SA 2.0)

And Red Scorpion hit all the cues designed to make red-blooded Americans cheer. Lundgren plays a Russian special forces operative brought to an unnamed African nation, ordered to assassinate an anti-communist military leader. Instead, he switches sides and joins a group of freedom fighters in beating down the Soviets. It’s the Cold War in desert heat, essentially.

Shapiro-Glickenhaus Entertainment, the distributor of Abramoff’s film, benefited from the film business’ shifting trends. The home video market was blowing up, and premium cable ensured that even a terrible film could have life beyond the box office.

That’s why Shapiro-Glickenhaus films like Maniac Cop and Frankenhooker, despite being poorly-reviewed trash, are still fondly remembered by audiences with cable back in the day.

While these trends ensured Red Scorpion could be made and would have an audience, it also meant that it was far from unique in the market. Cannon Films, another independent filmmaker of the era and the subject of an amazing documentary, was making dozens of films just like this one every year, relying on a stable of well-remembered B-list action heroes like Chuck Norris, Charles Bronson, and Jean Claude Van-Damme.

But only Red Scorpion had Abramoff, making it, in some ways, the more interesting cultural document, since one thing to understand about Abramoff was that his Hollywood career and his lobbying career weren’t separate—they were like a giant melting pot of influence and propaganda.

The film poster for Red Scorpion. (Photo: Courtesy Shapiro-Glickenhaus)

In fact, Red Scorpion was effectively funded by the South African military, mainly because the country was Abramoff’s primary client at the time. If you watch the movie, you’ll notice, for example, that the tanks are South African.

At the time, South Africa was facing a cultural boycott due to apartheid, and a 1986 U.S. law made it clear that doing business with South Africa was frowned upon.

That did not deter Abramoff, probably because the film was meant in part to combat the boycott.

“There was some indication even in those days that he was not the sort of person who would feel overly constrained by the rules,” said Jeff Pandin, a colleague of Abramoff’s in the era, in comments to Salon.

In 1986, Abramoff launched and headed an organization called the International Freedom Foundation, an organization that portrayed itself as an anti-Communist political think tank. In reality, though, it was a group meant to give some positive press and political cover to the South African government at a time when they were being pressured to release Nelson Mandela.

(Abramoff wasn’t the only lobbyist-type backing South Africa at the time; as The Nation notes, Abramoff’s old friend Grover Norquist, known these days as an anti-tax hound, visited a conference in South Africa intended to unify Americans in support of ending the anti-apartheid movement.)

The ties to South Africa led to some unusual production decisions. The film’s budget doubled to $16 million after Abramoff decided at the last minute to move production of the film from Swaziland to South West Africa, a country more than 1,000 miles away. The country, then controlled by South Africa, is now known as Namibia.

Nelson Mandela in 1993, with President Bill Clinton. (Photo: National Archives P05139-22a)

Looking below the surface points of the plot—the parts involving Dolph Lundgren brandishing guns—the film was roughly based on the life story of Jonas Savimbi, an Angolan military leader who was considered a South African ally and a noted anti-Communist.

All these things made the film controversial even before shooting had completed. Arthur Ashe, the late tennis star and anti-apartheid activist, spoke out against the film during its production, calling it an “endorsement of South Africa’s policies.”

Members of the movie’s crew found the funding for the film distasteful.

“We heard that very right-wing South African money was helping fund the movie,” actor Carmen Argenziano, who played a Cuban colonel in the film, told Salon in 2005. “It wasn’t very clear. We were pretty upset about the source of the money. We thought we were misled. We were shocked that these brothers who we thought were showbiz liberals—Beverly Hills Jewish kids—were doing this.”

The movie ultimately came out in April of 1989—less than a year before Mandela was released from captivity.

And while the film failed to gin up support for South African leadership, in the ensuing years, it did become an effective calling card for Abramoff when he finally returned to Washington in the 1990s.

A Boycott Apartheid bus in London, in 1989. (Photo: rahuldlucca/CC BY 2.0)

As for Dolph Lundgren, he remembers the production more for the fact that he did his own stunts rather than the controversy.

“It was South Africa, so a lot of the guys I was working with and training with were real soldiers,” the Swedish actor recalled in a 2011 interview with the now-defunct site Mondo Video. “My gun instructor went off on the weekends and killed some people. You know, some actual terrorists. He came back and told us the story of how he shot some guy who was trying to blow up a pipeline. I did a lot of light firing exercises with these real South African soldiers. They were S.A.S regiments from Rhodesia. It was pretty intense.”

In one scene, he had scorpions walking all over him.

“Jesus, I did so many crazy stunts on that film,” he recalled. “It’s unbelievable when I think back about it. It would never happen today. Nobody would ever let you do any of that stuff now.”

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook