When Giant Sequoias Were Sacrificed for Traveling Sideshows

In the beginning, Western settlers weren’t very kind.

During the second half of the 19th century, when traveling sideshows were all the rage, the so-called wonders of the world were taken from city to city to be gazed upon by spectators aching to see bearded ladies, tattooed men, and other “curiosities” that often fed the colonialist fantasies of the Western mind. But among many of the attractions included in such shows there was, at one point, an unlikely protagonist: the giant sequoia of the Sierra Nevada.

Native only to this California region, giant sequoias are some of the most ancient and massive beings in the world. The largest specimen, the General Sherman Tree, is the biggest single-unit living organism in mass and volume in the planet. It stands at 275 feet above the ground, and weighs around 1,900 tons. The oldest known sequoias are about 2,500 years old.

Indigenous groups had known about the existence of the giants, but they remained unknown to western settlers until the 19th century, when, in 1851, a pioneer named A.T. Dowd, who was pursuing a bear, stumbled upon the Calaveras Grove at what is now Yosemite National Park. Word spread quickly, and nationalists claimed sequoias as proof of America’s greatness, while scientists from all over the world prepared their luggage and set out to see the trees with their own eyes. Some businessmen, meanwhile, were thinking of profits.

The initial reports and pictures of trees that rose hundreds of feet above the ground and had circumferences of more than 30 feet were, as could be expected, met with skepticism, often aggravated by inaccurate and exaggerated reports.

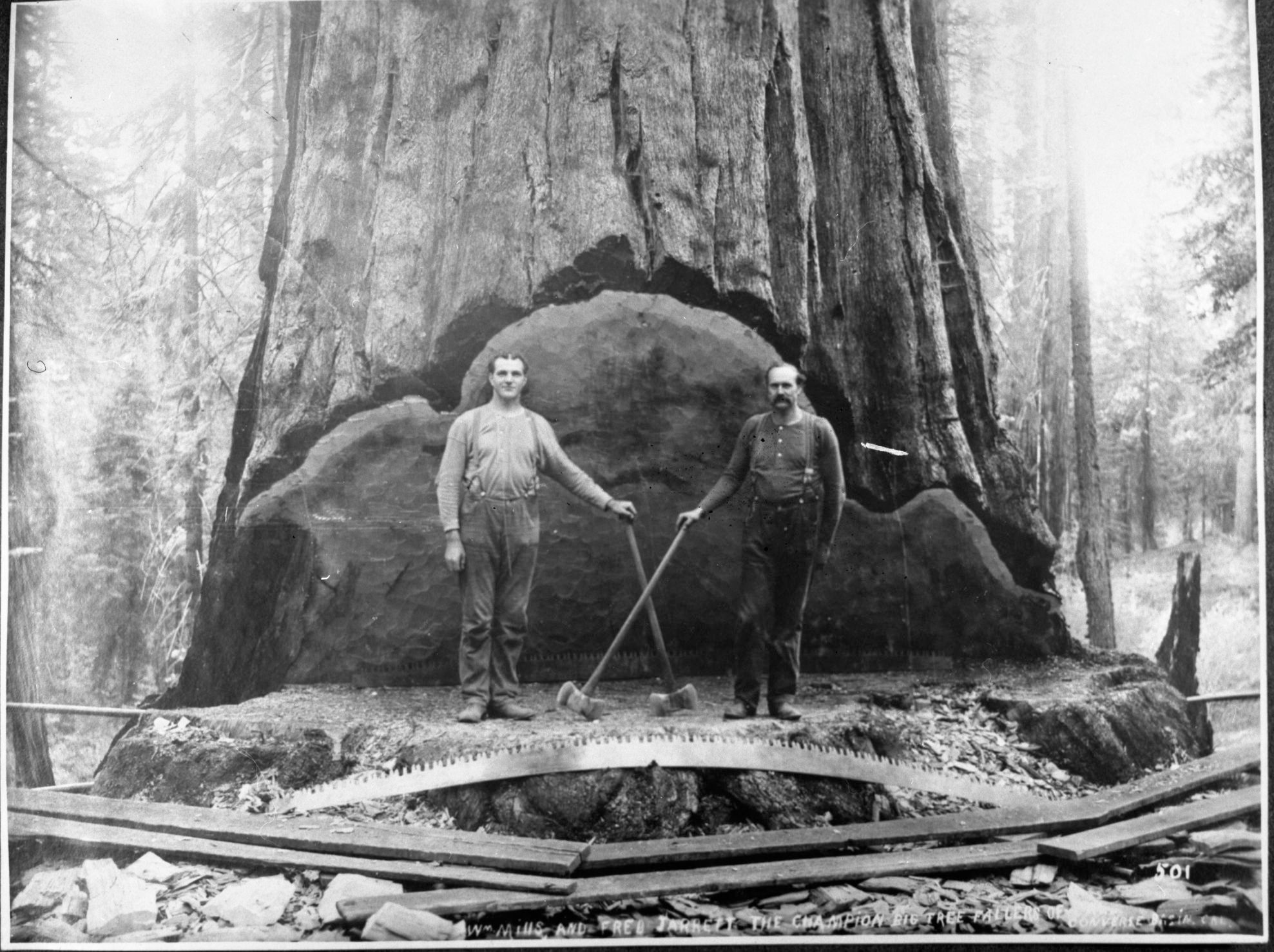

But it was a desire to monetize that skepticism and curiosity that motivated entrepreneurs like William Hanford, who bought the Discovery Tree, and with much toil, mining equipment, and steely resolve, felled it. His idea was to take the tree on a sort of traveling sideshow tour and charge people to see it.

An article published in 1853 in Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion V.5, describes the process:

[The tree] was taken off in sections, so that it can be placed, relatively, in its original position, and thus give the beholder a just idea of the gigantic dimensions of the tree. […] Probably it will not be very long, therefore, before our readers will be able to get a view of this monster of the California woods for a trifling admission fee.

The Discovery Tree was then taken to San Francisco, where people paid 50 cents to see it, and eventually to New York. Ward Eldredge, Curator of the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, explains that it was a “big deal,” describing it as a sort of Coney Island experience, where the tree would be erected temporarily and people would line up to buy tickets to see it.

Yet, despite the public’s overwhelming curiosity, Hanford’s costly and arduous project did not prove profitable. The necessity of cutting and reassembling the giant made it appear fake, as spectators claimed it had been assembled from several trees. This was in part because some of the same spectators had fallen for P.T. Barnum’s hoax, which displayed what was actually a coastal redwood.

This failure, however, did not stop others. A tree named Mother of the Forest was the next victim, though this time, the tree was not felled, but rather peeled using scaffolds. The Discovery Tree and the Mother of the Forest were two of only three sequoias known to non-indigenous groups at the time, according to Michael Theune, Acting Public Affairs Officer at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. “And we killed two of them,” he says.

The plank peeled from the Mother of the Forest was around a hundred feet, proof of the astonishing size of the trees, yet without the need to cut and reassemble. It eventually made its way to the Crystal Palace in New York, before crossing the Atlantic to be exhibited at the larger Crystal Palace in London, where it was a huge success. The scarred tree remains standing, if also partially consumed fire and dead. The plank itself was destroyed along with the London Crystal Palace in an 1866 fire.

There were, of course, several other trees that met similar fates, and it’s even said that P.T. Barnum himself managed to acquire a legitimate sequoia plank for his shows. Others were taken to cities across the U.S., displayed at events like centennial anniversary of the American Declaration of Independence and the 1893 World Columbian Exposition.

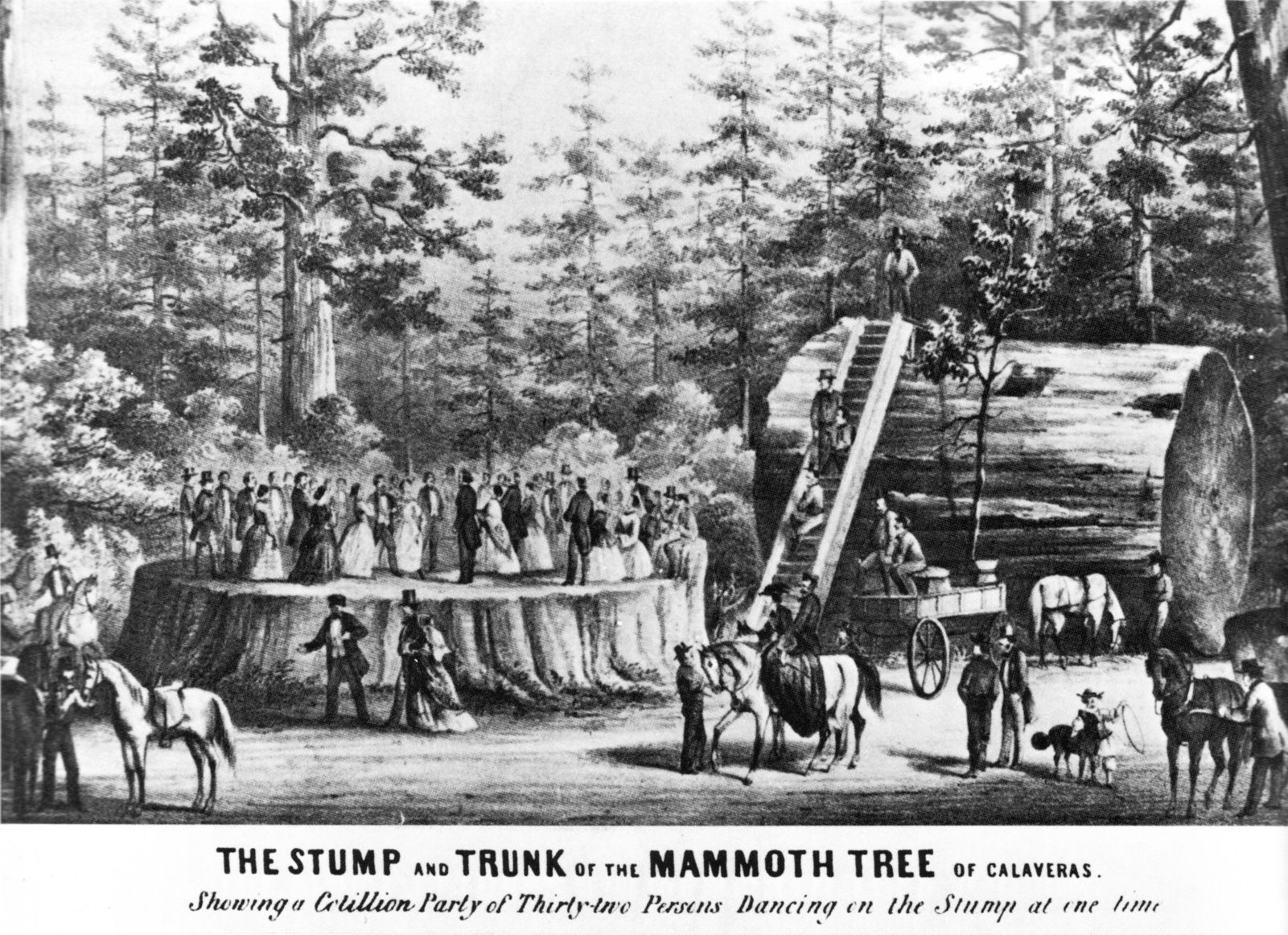

Exhibitions, though, weren’t the only way people tried to profit off the sequoias. The Mammoth Tree Hotel started to be constructed in 1853 close to where the Discovery Tree Stump was located. A bowling alley was built on top of the body of the fallen tree, while dances and other events were held on its stump.

And then there was the lumber industry, which thought it had struck green gold. It was soon discovered, however, that the destructive fall rendered a large percentage of the tree unusable, and that the wood of sequoias was surprisingly brittle and unfit for manufacturing. Most of the harvested sequoia wood, in the end, was used for matchsticks, fences, and pencils. The lumber industry later gave up, discouraged by the low profit and the ever-growing outcries of conservationists, but not before causing heavy damage on the existing sequoia population, or as much as 34 percent in some areas.

Almost from the beginning, at any rate, there was criticism, like that of the naturalist John Muir, who said that peeling the Mother of the Forest was “as sensible a scheme as skinning our great men would be to prove their greatness.”

Sequoia National Park, Yosemite National Park, and General Grant National Park (later incorporated into Kings Canyon National Park), were created in 1890, while the Calaveras Grove, the site of the Discovery Tree, became protected in 1931. Today, the giant sequoias are considered one of the natural gems of the world, though some of the damage can still be felt, like earlier this month, when the famed tunnel tree fell during a storm.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook