Why Can’t the World Just Pick One Design for Plugs?

(Photo: BillionPhotos.com/shutterstock.com)

A version of this post originally appeared in the Tedium newsletter.

When you travel internationally, power outlets provide a pretty good reminder that you’re not in Kansas anymore.

Outlets vary wildly depending on the part of the world, both in the shape of their sockets and the voltage with which they’re compatible. For those who travel across multiple regions, it can be frustrating. And it’s probably too late to solve this problem, because of decisions made more than a century ago.

Let us zap back to the War of Currents, which kicked off in the 1880s. While Thomas Edison was getting all the attention for his take on the incandescent light bulb—and leveraging that attention into building an electric company, based on direct current (DC) energy, that would bring light bulbs to the masses—Nikola Tesla was trying to convince others he had a better approach. One strategy Tesla used involved him shoving 250,000-watt shocks of electricity into his body in order to prove that alternating current (AC) electricity was safe. The fact that he survived made a pretty compelling case.

Tesla’s AC patents, which he had sold to Westinghouse in 1888, proved more effective in the long run—in part because DC energy was harder to convert to slower currents as needed at the time. While Edison remains perhaps the stronger of the two inventors from a reputation standpoint, most energy around the world is distributed through AC. Point for Tesla.

The surprising part about all this fighting over electric currents is that things we take for granted today—specifically, electric outlets—were not a given at first. In fact, if you had a house lit by electricity around the turn of the 20th century and wanted to move the furniture around your home, you probably wouldn’t have been able to do that all too easily. That’s because, for the first couple of decades after the invention of electricity, electric power meant lighting, and lighting was hard-wired into the walls, requiring the literal tearing down of walls to move things around.

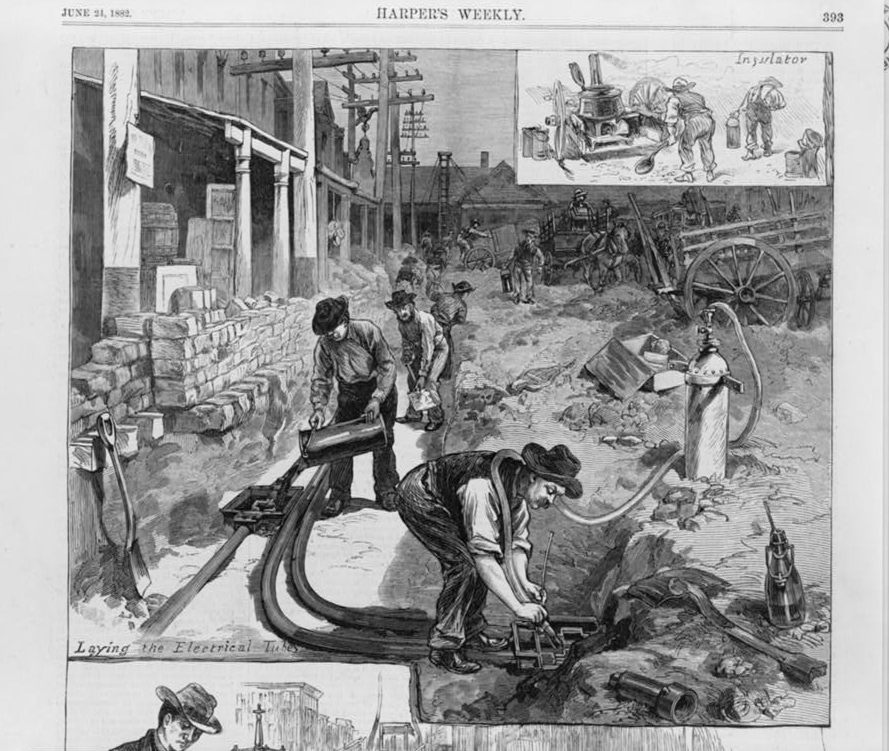

An illustration from June 21, 1882, of laying the tubes for electric wires in the streets of New York City, in order to wire houses. (Image: Library of Congress)

Fortunately, however, inventors were working on the issue. In the 1890s, electric plugs were already being put into use in Europe, and in the early years of the 20th century, inventor and manufacturer Harvey Hubbell came up with an easy way for users to unplug a light bulb from a socket and replace it with another device fairly easily. Here’s the reasoning for Hubbell’s approach, according to his 1904 patent filing:

My invention has for its object to provide a separable attachment-plug in which the cost of construction shall be reduced to the minimum and which shall do away with the possibility of arcing or sparking in making connection, so that electrical power in buildings may be utilized by persons having no electrical knowledge or skill in the use of tools in attaching lights, fans, motors, heating apparatus, surgical instruments, or any of the various appliances requiring the use of an electric current to fixtures in the circuit, the removable parts being interchangeable and one of said parts being connected to each light, group of lights, fan, or other appliance which it may be required to place in the circuit.

Hubbell’s approach took some time to win over a broader audience, in part because it required other manufacturers to sign on to the concept, and in part because homes were not wired for wall-based plugs—meaning that, if you wanted to plug into your home’s electric current, you had to pull out a light bulb and replace it with a plug. But by the early 1910s, Hubbell plugs and competing variants slowly gained prominence, beating the approach encouraged by Edison’s company—the use of attachment plugs, which used light sockets as outlets.

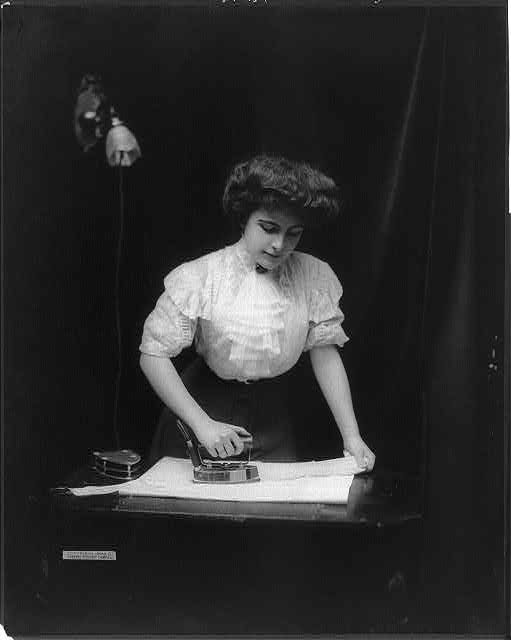

A woman uses an electric iron plugged into light socket, c. 1908.. (Photo: Library of Congress)

By the time that Hubbell’s plugs created a way forward for electricity, however, it was already too late to standardize internationally. In the United States and much of the Americas, most power outlets use a fairly compact two-prong or three-prong outlet, which evolved from the Hubbell plug. Eventually, it gained a grounding plug as a way to prevent electric shock, thanks to the help of an engineering student from Milwaukee. Japan uses a roughly similar layout for its plugs, but with some slight differences, including differences in voltage and a heavier reliance on the two-prong standard.

The United Kingdom perhaps has the bulkiest and most unusual plug type, one significantly larger than any other kind you’ll run into around the world. But that size and design actually of huge benefit, because it means that it’s basically impossible to get electrocuted by a UK power outlet, unlike its American counterpart. It’s incredibly well-designed. (However, an older plug that isn’t nearly as well-designed still remains in use in former British colonies such as India.)

British plugs. (Photo: Deucharman/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Outside of the UK, most countries in Europe have small variations in the ways that their plugs work, but travelers throughout Europe don’t have issues with this because the plugs generally have a consistent two-prong setup. The majority of European countries use the “Schuko” format, which was introduced in Germany in the 1920s, but variations specific to France, Denmark, and Switzerland add their own quirky twists. Fortunately, the Europlug standard used for many devices ensures that travelers aren’t totally screwed if trying to travel between countries.

The Europlug. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Israel and Palestine might not have a lot of common ground on many diplomatic and political issues, but one place where they agree is with their unusual three-pronged electrical outlets, which feature a grounding prong close to the center of the plug. It’s compatible with the Europlug, fortunately.

Two Israeli plugs—the left is the old standard, the right is the 1989 revision. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In Australia and China the most common type of power outlet features slanted plugs. It’s roughly similar in size to the common U.S outlet, however. That’s in large part because the design was originally based on a patented Harvey Hubbell design.

An Australian outlet. (Photo: Alikai/Flickr)

Different countries use different types of voltage, and chose to do so without considering the fact that people might want to travel around the world and plug in their iPad no matter what country they’re in. The U.S., for example, standardized on the 120-volt system at a 60 Hz frequency, but at the same time, Germany was making up its mind that a 220- to 240-volt system at 50 Hz was a better idea. And in Japan, half the country uses a 60 Hz frequency while the other half uses 50 Hz—something that created big headaches and ensured that inconsistencies between the various systems abounded. These inconsistencies followed their way to the outlets as well.

“There are standards, and there is a plug that has been designed,” the International Electrotechnical Commission’s Gabriela Ehrlich explained to Gizmodo in 2009. “The problem is, really, everyone’s invested in their own system. It’s difficult to get away from that.”

The differences between all these power outlets lead to some weird half-solutions that you might run into in a hotel room or hostel. In countries outside of North America, 220-240 volt energy is more common, but that level is dangerous for using devices in a restroom, due to the fact that there’s water nearby. That’s led to the creation of “shavers only” outlets, which are designed for devices like hair dryers or electric razors, essentially limit the amount of voltage that goes through the outlet to a level that won’t kill you if you try to plug something in. Whew.

A dual-voltage shaver socket. (Photo: Pfnicholls/Wikipedia)

If electric outlets stand a chance of finding common ground in the future, the savior might come in the form of direct current. You can thank the rise of computers for this shift. Most modern electronics, such as laptops and smartphones, rely on DC energy, with the devices getting converted to AC power through the usage of adapters. That power block separating your laptop from the wall? It’s sort of a peace offering between Edison and Tesla, if you think about it.

DC power outlets aren’t unheard of, either; most modern cars have one, which you might know better as a “cigarette lighter” socket. And certain airplane seats feature traveler-ready variants on DC power outlets called EmPower. These devices offer as many as 15 volts of electricity to passengers—enough to keep a laptop plugged in. And because EmPower is direct current, your laptop doesn’t need a bulky AC adapter like it usually does.

The problem is, outside of airplanes, the port isn’t very common, and as a result, it can be frustrating for consumers who have to buy yet another cable to charge their laptops.

Fortunately, there’s already a solution to this giant mess of cables and connections, and it’s a trojan horse introduced by the tech industry nearly two decades ago: the USB port. It’s a simple format that is smaller than all electric outlets and offers up just enough power to give nearly all small devices the proper push. And it’s already in wide use.

A British power outlet with a USB socket. (Photo: ben_osteen/flickr)

Over the years, USB has become an accepted standard for computer cables, but also a de facto standard for electric charging—thanks in large part to a move by most mobile phone makers to embrace micro-USB as a standard port. And a USB cable is likely to work with any kind of laptop or outlet, no matter if you’re in Menlo Park or Madagascar. It’s common these days to find wall outlets with USB ports built right in, and even airplanes have started to offer built-in USB ports on long-haul flights.

USB is the stealthy comeback game of direct current, and we’re already using it. Could it eventually replace all those plugs and cables sitting in your bags? It’s not 100 percent clear if it ever will, but if it does, Edison might still topple Tesla after all.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook