Why Women Led Anti-Suffrage Campaigns Against Themselves

Why deprive oneself of the right to vote? It’s complicated.

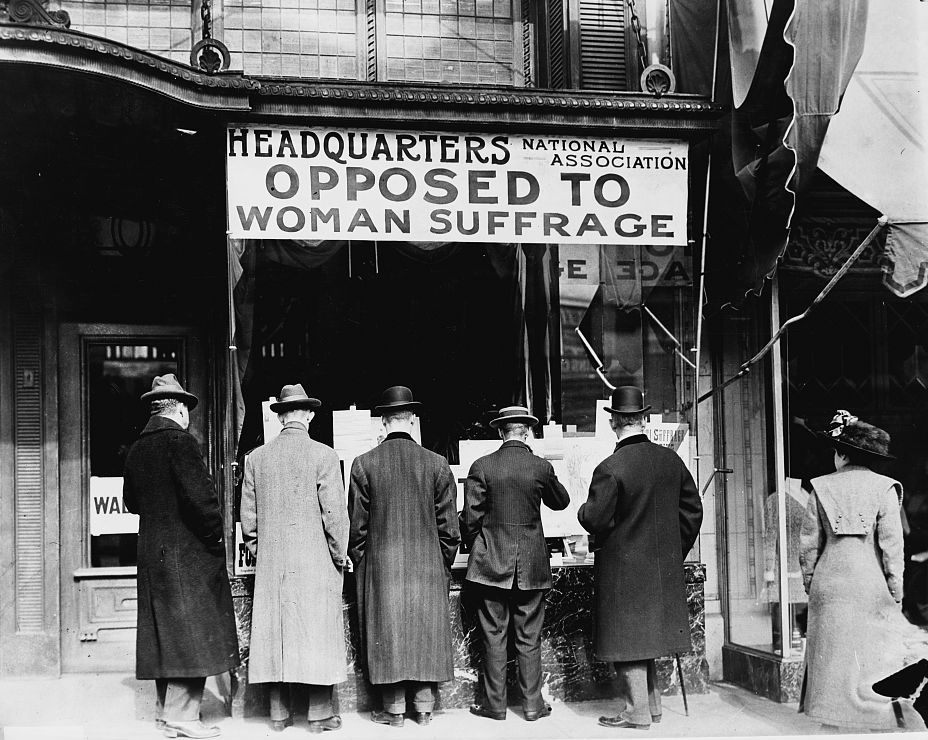

Men looking at material in the window of the National Anti-Suffrage Association headquarters. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-25338)

Just over 100 years ago, a pamphlet railing against the notion of women’s suffrage began circulating in Massachusetts. It declared that granting voting rights to women “would be detrimental to the best interests of the State.” Though those rabble-rousing suffragists seemed to be gaining ground, it said, they were in fact “a small body of intensive and fanatical women” who had enticed theretofore apathetic voters with “showy arguments, false war cries, and continuous strenuous endeavor.”

Another man threatened by female power? No, this pamphlet was written by a woman.

Mrs. Albert T. Leatherbee, as she credited herself, was one of a smattering of vocal female anti-suffrage campaigners in the United States during the early 20th century who fought to keep women from being granted the vote. Their reasons for wanting to be denied that right were more complex than you might think.

Dr. Susan Goodier, a SUNY Oneonta history lecturer, says that when she was researching her 2013 book, No Votes for Women: The New York State Anti-Suffrage Movement, “there were some people who said to me, ‘Oh my gosh, I can’t believe you’d want to write about those crazy people.’” The idea of women campaigning to deprive themselves of basic societal rights does seem like an act of unfathomable self-betrayal. But, still Goodier strove for empathy. “I promised myself that although I don’t agree with these people, it’s my responsibility to treat them with respect and try to understand where they were coming from.”

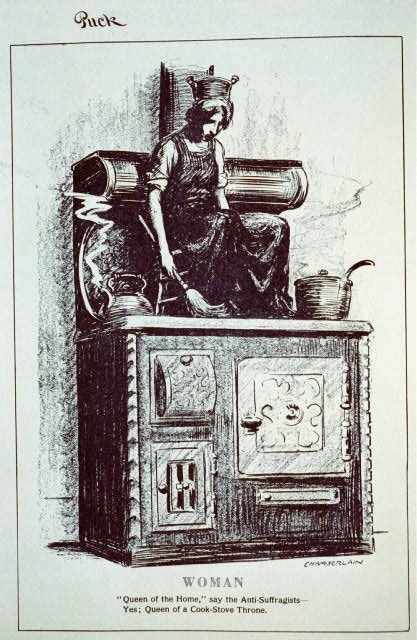

An anti-suffrage postcard, c. 1910.. (Photo: LSE/Public Domain)

Most of the female leaders of the anti-suffrage movement, says Goodier, “were earnest, intelligent, often educated and professional women who sincerely believed that women, and the nation-state, would suffer when women achieved political equality with men.”

Central to the movement was the then-prevalent notion that in order to be functional, prosperous and pleasant, American society required men and women to operate in separate spheres of influence: public life for men, and domestic life for women. These realms aligned with what were regarded as the inherent natural strengths of each sex. Women, who were considered nurturers, moral guardians, and peacekeepers, were expected to guide the moral development of the next generation by presiding over family and the home. (“Women is queen, indeed,” wrote Roman Catholic Cardinal James Gibbons, quoted in an anti-suffrage pamphlet, “but her empire is the domestic kingdom.”)

“Most nineteenth-century commentators saw strict differentiation between the roles of women and men as crucial to the proper functioning of the nation,” writes Goodier in No Votes for Women. “Anti-suffragists subscribed to the belief that women’s power base, the private home, was equivalent to the masculine power base in the public realm.”

Some of the anti-suffrage leaders in New York, left to right: Mrs. George Phillips, Mrs. K. B. Lapham, Miss Burnham, Mrs. Everett P. Wheeler, Mrs. John A. Church. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ds-01453)

An anti-suffrage petition published in the New York Times in 1894 railed against the granting of voting rights beyond men, framing such a shift as “the imposition of political duties upon women.” With so many domestic tasks to contend with already, it argued, women should not be further burdened with the responsibility of participating in elections.

These domestic duties went beyond caring for children, keeping the house clean, and serving up hot homemade meals to the family. The home realm that women ruled extended beyond the fall walls of one’s house, incorporating activist pursuits like community organizing, fundraising, and grassroots advocacy.

“Many of the women that you find in both the suffrage and the anti-suffrage movement were also involved in benevolent reform,” says Goodier. These women—white; middle- to upper-class; often married to men who were in politics or law—“came out of a 19th-century culture where women got involved in clubs and organizations that helped the poor, that worked in the hospitals … helping with people who were in prisons, children in orphanages, all kinds of activism like that.”

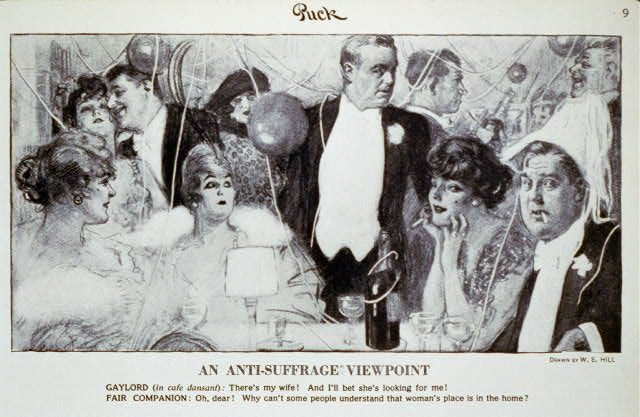

A satirical cartoon on the anti-suffrage movement. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZC2-1194)

This community involvement brought political influence. But for suffragists, such an unofficial arrangement was not enough. “Suffragists came to believe that their power was transient, that it wasn’t the kind of power that men had,” says Goodier. “Anti-suffragists, on the other hand, wanted that uniquely female power to reform, to help build the state. And many of them said that the state depended on that uniquely feminine way of helping their community and the state.”

These nurturing, “feminine,” community-based contributions to the nation precluded voting, which was a seemingly simple duty but, to the anti-suffrage crowd, carried a wealth of unwelcome responsibilities. “It is said that the casting of a vote is a slight duty, quickly performed,” read An Argument Against Women Suffrage, a pamphlet delivered before the Massachusetts Legislature’s special legislative committee in the 1910s. “If it were that simple mechanical act, we might not object to such action, but to cast a vote ought to mean to cast it intelligently and honestly; and how can we gain that accurate intelligence except by attending caucuses, primaries, nominating conventions, and supplementing general knowledge as far as possible by personal acquaintance with candidates?”

Such pursuits would draw women away from their domestic duties, disrupting the balance of a society in which gender essentialism dictated daily operations. Some anti-suffrage campaigners even claimed that granting voting rights to women would cause households to break down. “Woman Suffrage, by introducing a new element of discord into the family, tends to increase material infelicity and consequent divorce,” read the Massachusetts Anti-Suffrage Committee’s 1915 pamphlet, The Case Against Woman Suffrage. ”WOMAN SUFFRAGE IS THE LAST STRAW IN MANY A FAMILY.”

A cartoon in which a man argues for anti-suffrage, as a means of hoping his wife won’t see him with another woman. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZC2-1202)

The prospect of votes for women also posed a threat to the elite ladies who had grown accustomed to using their social status to exert political influence. Some of these women, writes Susan Marshall in Splintered Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Campaign Against Woman Suffrage, ”fought suffrage as a threat to their own positions of privilege.” Granting voting rights to all women would mean taking away some of their power. As the New York Times put it in 1894, “to give women the suffrage would only increase the ignorant vote and bring refined women into contact with an element that should not be brought into their lives.” To some rich and influential white ladies, democracy had its downsides.

In 1917, there was a major shift in the anti-suffrage narrative. Having witnessed a dozen states enacting voting rights for women—and an estimated 1.9 million women casting a vote in the 1916 presidential election—some anti-suffrage leaders invoked World War I to try to slow down the suffragists. “Senate should be respectfully urged to pass no measure involving such a radical change in our government while the attention of the patriotic portion of the American people is concentrated on the all-important task of winning the war,” read a senate petition from the Women Voters Anti-Suffrage Party of New York.

Of course, by this time it was too late to stop the suffragists’ momentum. The war ended the following year, more states joined the votes-for-women roster, and nationwide women’s suffrage arrived with the 19th Amendment in 1920.

A pin from the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League. (Photo: LSE/Public Domain)

Reflecting on the anti-suffragists’ less-known characteristics, Goodier cites a strong sense of civic responsibility. During their campaign, the responsibility was to uphold the government’s decision that women ought not to vote. But after their movement died, most of the anti-suffragists “did their duty and voted,” she says. “And many of them were proud of it.” The anti-suffragists were “very, very interested in politics, and had been all along, but not in the same way that suffragists were.”

In the years after the 19th Amendment, women on both sides of the fence saw their predictions fall a bit flat. “Many suffragists saw the vote as a panacea, that it would solve problems like low wages, bad working conditions, these kinds of problems that faced everybody in society,” Goodier says. Even more dramatically, Mrs. Albert T. Leatherbee’s 1915 Anti-Suffrage Campaign Manual claimed that feminist suffragists would bring about “a general conflagration of the present world upon which they shall raise a new heaven and a new earth.” Instead, change would come slowly, incrementally, and with much fewer hallmarks of the apocalypse.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook