Wild Poinsettias Can Grow Eight Feet Tall

A diplomat, a scientist, and a farmer tamed the blazing red plant into a commercial juggernaut.

The poinsettia, a red-leafed plant that appears everywhere around Christmastime, first came to the United States in the late 1820s. Like many of America’s Thanksgiving staples, the poinsettia is an immigrant from Mexico, where it’s called the flor de noche buena, the Christmas Eve flower. In the U.S., we call it poinsettia after the man who brought it here, Joel R. Poinsett, who was sent south as a special envoy after Mexico won its independence from Spain.

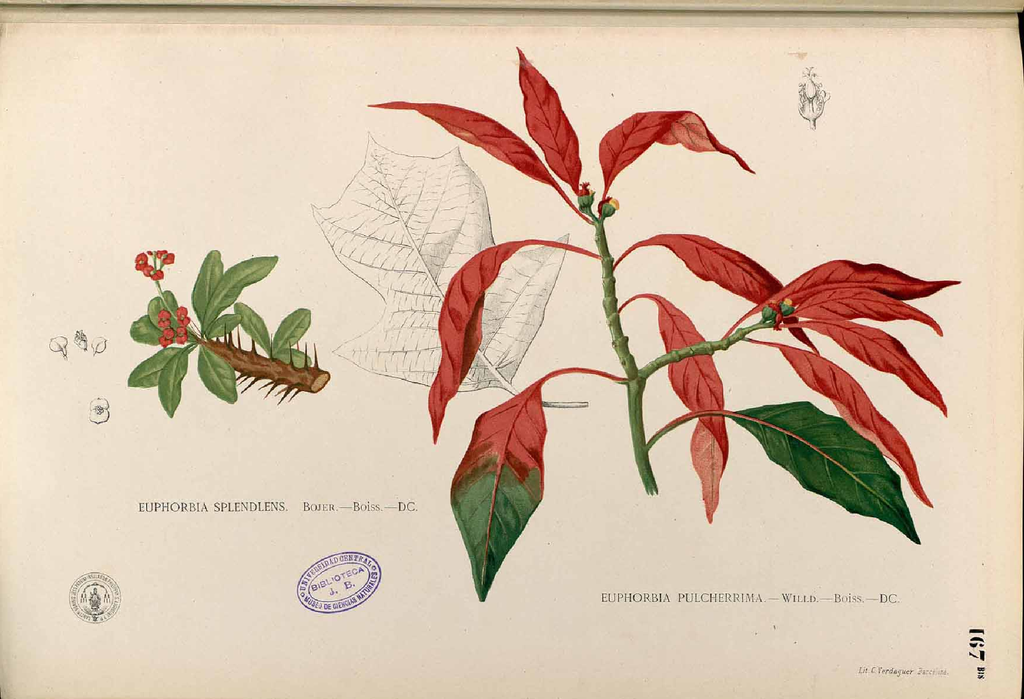

The plant that Poinsett encountered would not necessarily have looked like the short and bushy plant that crowds courtyards today. In the wild, poinsettias can grow into a tall and rangy tree, up to eight feet tall, with blazing red leaves. It’s a dazzling plant, as its scientific name hints—Euphorbia pulcherrima, the most beautiful plant in the genus Euphorbia.

Poinsett sent back clippings to grow in a South Carolina greenhouse and for years would share specimens with friends and botanical gardens. But it wasn’t until the 1960s, with the support of the government and one California farmer with a penchant for promotion, that the poinsettia was rebuilt for mass production.

By then, the plant had become a symbol of Christmas in America, too, and poinsettias would show up in fancy lobbies and other public places as a sign of the season. The plants lasted only a few days before their leaves would wilt and drop, though. They were temperamental, hard to coax into flowering at just the right time to head to market.

To H. Marc Cathey, that was a challenge. As a horticulturist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, part of Cathey’s job was to create plants that growers could sell—to help create markets for plants people didn’t even know they wanted to buy. While researching which chemical controls plant growth (a relatively new field at the time), he found a few compounds that would, first of all, keep the poinsettia small and bushy, a compact plant fit for a house instead of a tree fit for the wild. He also discovered a trick to hold the plants back from flowering: Every night, from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m., he would flash the plants with three seconds of light each minute, which would confuse them enough that they held their flower fire.

At the same time, a family of poinsettia farmers in California were working to develop plants that would stand up better to life indoors and that would flower longer. The Ecke family had first focused on the poinsettia in the 1910s, when paterfamilias Albert Ecke started specializing exclusively in poinsettias. His son, Paul Ecke, Sr., grew the businesses into a large poinsettia operation, and in the 1960s his grandson, Paul Ecke, Jr., pushed his father to modernize, installing greenhouses, selling cuttings instead of full-grown plants, and starting a breeding program to create more commercial plants.

By the end of the decade, the plant had been fully transformed into the commercial product of today, and its popularity started to grow. By 1986, it edged out the chrysanthemum as America’s best-selling potted flowering plant (a spot it kept for decades, until edged out by orchids at the end of the 2000s). In the next decades, poinsettia would become $200 million industry, to the great triumph of the Ecke family. At one point, 90 percent of all poinsettias sold started life at the Ecke Ranch.

Today it’s possible to buy poinsettias in all manner of colors, with leaves of orange, pale green, or a creamy, marbled pink. But the classic is still the blazing red plant that first attracted the interest of Joel Poinsett. If you live in the right climate, you might even consider planting poinsettias and letting it grow to its full, glorious height—even if it only displays its best show of leaves and flower for a fleeting moment, just before Christmas.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook