Wildly Beautiful Photographs of Flamingos From the Air

East Africa’s soda lakes have some stunning sights.

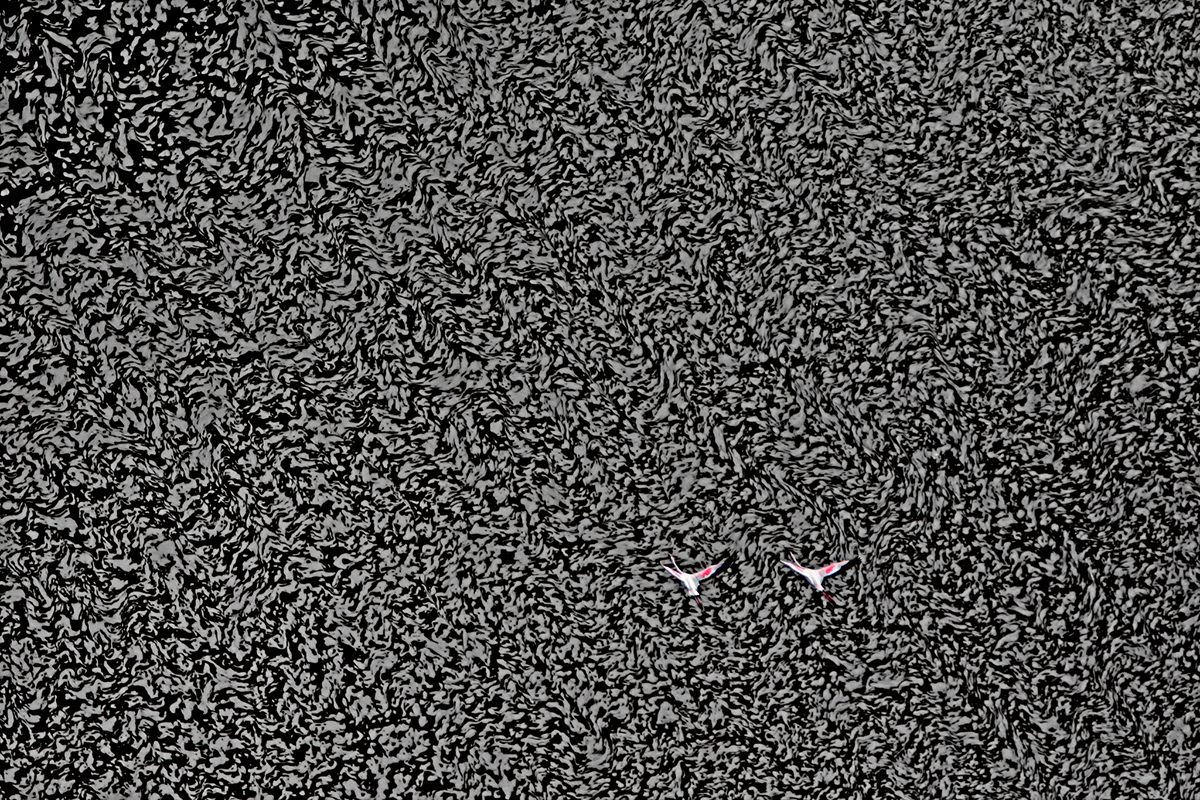

An aerial view of Lesser Flamingos feeding in the shallows of Lake Natron, Tanzania, leaving trails in the mud. The lake has mineral-rich waters and mud that are caustic to most other animals. For flamingos, it’s a safe haven and an ideal breeding ground. (All Photos: Paul McKenzie)

A version of this story originally appeared on bioGraphic.com.

The classic flamingo silhouette is instantly recognizable: a ball of pink feathers perched on one thin leg, long neck curved as a beak tilts towards the water for food. It’s an image so well-known it’s been immortalized in kitschy plastic lawn ornaments.

But from the air, a flamingo has a different appeal. In the Lesser Flamingo habitats of Tanzania and Kenya, bright pink specks wade through dark water, leaving painterly trails in their wake. A cluster of birds flies over a monochromatic lunar landscape. A vast flock dots a sea of green.

“It was like nothing I’ve seen anywhere on our planet,” says photographer Paul McKenzie, who flew over these flamingo habitats to capture images of the birds from above.

In northern Tanzania, by the border with Kenya, Lake Natron’s shallow, highly alkalized water is a breeding ground for around three-quarters of the world’s population of Lesser Flamingos. As with neighboring Kenya’s Lake Bogonia and Lake Logipi, also home to the flamingo, the water in this soda lake is so corrosive it can burn through skin. But for the flamingo, it’s not only a place to breed, but feast. The waters, which measure over 35 miles long and 14 miles wide, are dense with spirulina, which the flamingo gathers with its head upside-down, sifting with its beak.

This unique environment also creates some peril for the birds, which are classified as “Near Threatened.” There have been proposals to mine for soda ash at Lake Natron, which would have a deleterious effect on flamingo populations.

For now, though, as these photos show, the birds thrive. Take a glimpse at what McKenzie calls a most charismatic species in its extraordinary natural environment.

The flamingos wade through an algae slick on Lake Logipi in Kenya.

“Flamingos have not only managed to survive in these conditions, they positively thrive. It’s a triumph of evolution that they’ve adapted to these hostile environments,” says McKenzie.

Flamingos at Lake Logipi in northern Kenya.

Leaving their trails behind as evidence of their last stop, lesser flamingos fly over the silt-infused water of Lake Logipi.

Flying over Lake Natron, a breeding ground for about three quarter’s of the world’s population of lesser flamingos. The lake has been threatened several times in the past decade by proposals to mine the lake for soda ash.

A flock flies over Kenya’s Lake Logibi in search of feeding grounds. The bright birds preferentially eat the algae Arthrospira fusiformis, which tints their feathers pink with the pigment molecules and nutrients the algae contain.

Flamingos flying over an algae bloom in Kenya’s Lake Bogoria. The flamingos’ inextricable link to the soda lakes makes them vulnerable to a changing climate and human activity.

Tanzania’s Lake Natron, with its swirls of concentrated sodium compounds, provides a mesmerizing backdrop for a pair of lesser flamingos.

Thousands of lesser flamingos congregate in the algae-rich water of Kenya’s Lake Logipi.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook