Yosemite National Park

Though many hidden places need our attention, sometimes places on the very beaten path call loudly to the adventurer and wanderer inside us. Four million people a year go to Yosemite, and in 2010 I am one of those visitors. It’s crowded in Yosemite Valley on the weekends, and the most popular trails can feel like a mall on the day after Thanksgiving. A really, really beautiful mall. But, with a little effort, you can get away from the throngs and enjoy what the conservationist John Muir did.

If, like me, you don’t know that much about geology, Yosemite looks like the stuff of myths. Here is a cursory summary of the geological history of Yosemite Valley and surrounding environs. The granite masses that make up Yosemite were formed between 210 and 80 million years ago when they were still far below the surface of the Earth. Heat and pressure melted rock into the granite that we see now. Shifts in the Earth’s tectonic plates pushed the granite closer to the surface. In the last Ice Age (about two million years ago), glaciers formed and pushed more dirt off the rocks. As the glaciers melted and reformed, the layers of dirt and rock were pushed off again and again. Finally, erosion from wind and sun wore away the uppermost layers of dirt and rock, exposing the expansive granite faces we still see today. The massive faces remain bare because winter freezing removes young plants from the surface.

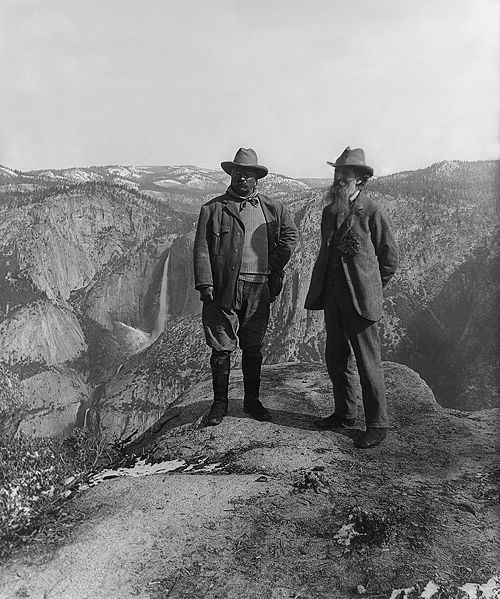

John Muir and Robert Underwood Johnson pushed Congress to protect Yosemite because the timber industry and sheep were slowly destroying it. Though sheep are benign looking creatures, Muir called them “hoofed locusts” for how much they ate. Yosemite became a National Park in 1890. Despite his success, Muir continued lobbying Congress to expand the park. When President Theodore Roosevelt visited in 1903, Muir convinced him to add Yosemite Valley and the Maripose grove of Giant Sequoias to the protected land.

John Muir and Robert Underwood Johnson pushed Congress to protect Yosemite because the timber industry and sheep were slowly destroying it. Though sheep are benign looking creatures, Muir called them “hoofed locusts” for how much they ate. Yosemite became a National Park in 1890. Despite his success, Muir continued lobbying Congress to expand the park. When President Theodore Roosevelt visited in 1903, Muir convinced him to add Yosemite Valley and the Maripose grove of Giant Sequoias to the protected land.

Yosemite today is populated with an odd mix of die-hard backpackers and tourists. I fall somewhere in the middle. Inevitably, the farther you climb, the smaller the crowds. On the Mist Trail – the most popular trail in a very popular park – the first climb brings you 1200 feet up to the top of Vernal Falls, a waterfall that sprinkles on you most of the way up. If you have the energy and stamina to make it up to Nevada Falls, another 600 feet up, you will be rewarded with stunning views and a near-empty peak. If you are like me, you may not be able to feel your calves the next day. (If you continue on to Half-Dome, you may not make it back by nightfall.)

As the snow melts from the Sierras every spring, waterfalls erupt throughout the park and gush until the snow is all melted, usually by the middle of summer. Yosemite Falls is the tallest freefall waterfall in the United States. The viewing area at Lower Yosemite Falls is very crowded. You can hike up to Upper Yosemite Falls for a rarer view and stand on a fenced ledge at the top of the Falls.

Also, if you travel out of the Valley the trails will not be nearly as populated. Behind Tunnel View, a very popular photo spot, there is an underused trail, Inspiration Point. Climb a bit to get away from the crowds, and enjoy the breathtaking view without tripods cluttering the scene.

Reservations must be made months in advance, please see the National Park Service website for details.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook