You’re Missing Shakespeare’s Best, Most Sophisticated Boner Jokes

Well, unless you’re a reanimated Elizabethan.

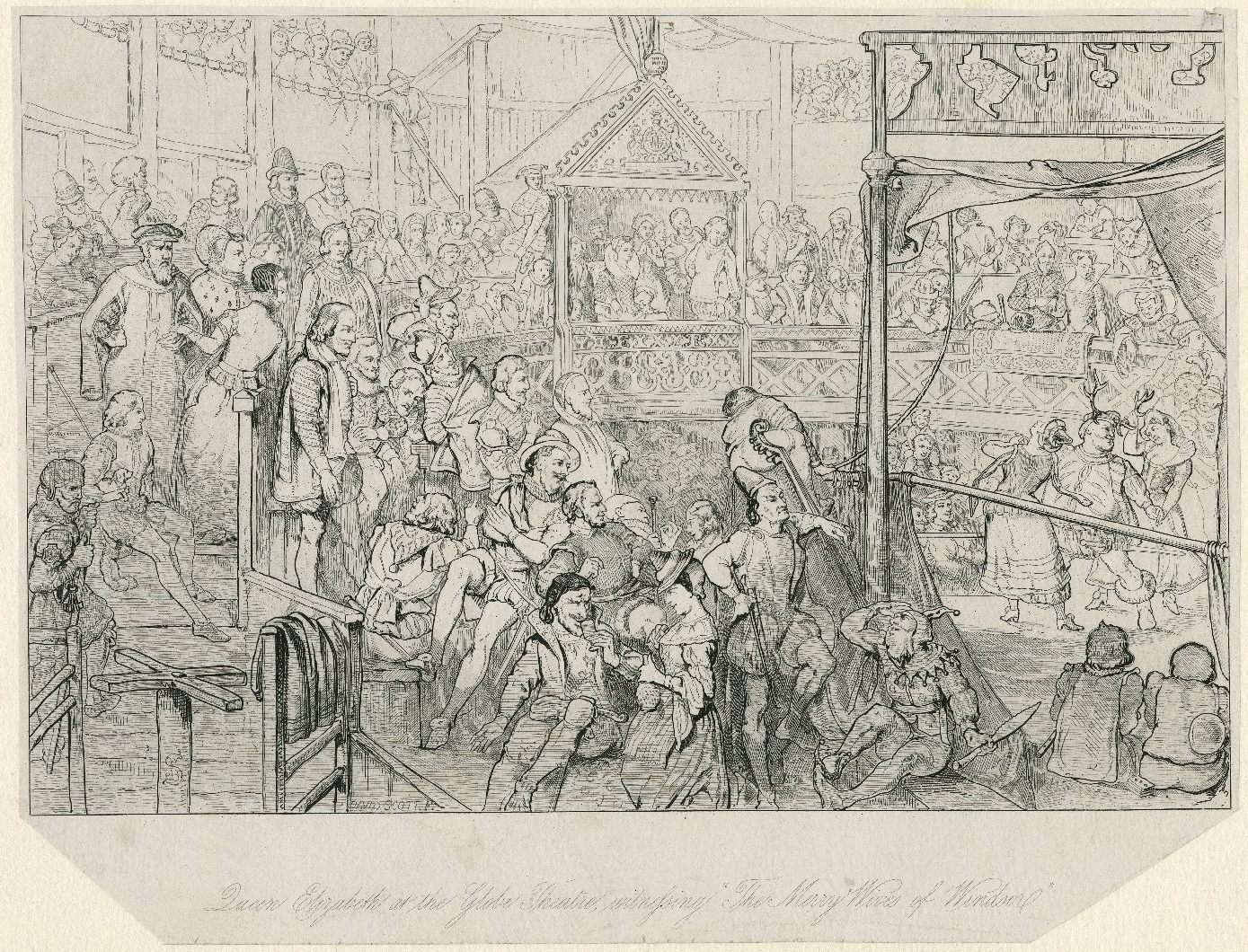

An early 19th-century depiction of Queen Elizabeth I at the Globe, watching The Merry Wives of Windsor. (Photo: Folger Shakespeare Library/CC BY-SA 4.0)

It’s no secret to anyone who’s taken freshman English that William Shakespeare loved—loved—puns. Helge Kökeritz’s classic 1953 book Shakespeare’s Pronunciation lists many dozens of them, from “pasture”/”pastor” to “fleece”/”fleets.”

Whether these puns are an example of the Bard’s brilliant wit or a superficial distraction from it depends on which critic you talk to. Samuel Johnson, the author of the most authoritative English dictionary before the OED, was definitely in the latter group. Punning “has some malignant power over [Shakespeare’s] mind,” Johnson wrote in a preface to an edition of Shakespeare’s collected works in 1765.

However you feel about Shakespeare’s puns, though, one thing’s clear: most readers (including Samuel Johnson) have missed a lot of them. English pronunciation has changed a great deal since Shakespeare wrote his plays, with the result that many words that were homophones then no longer sound that way now. For instance, can you spot the pun in these lines from Taming of the Shrew?

LADY: I hope this reason stands for my excuse.

BEGGAR: I, it stands so that I may hardly tarry so long.

No? That’s understandable—contemporary pronunciation is in your way. In Elizabethan times, the “ea” in “reason” would have been pronounced like the “ai” in “raising,” yielding a dirty joke: the beggar is joking that he can’t tarry because he has a boner (a “raising”) to attend to. (Groan.)

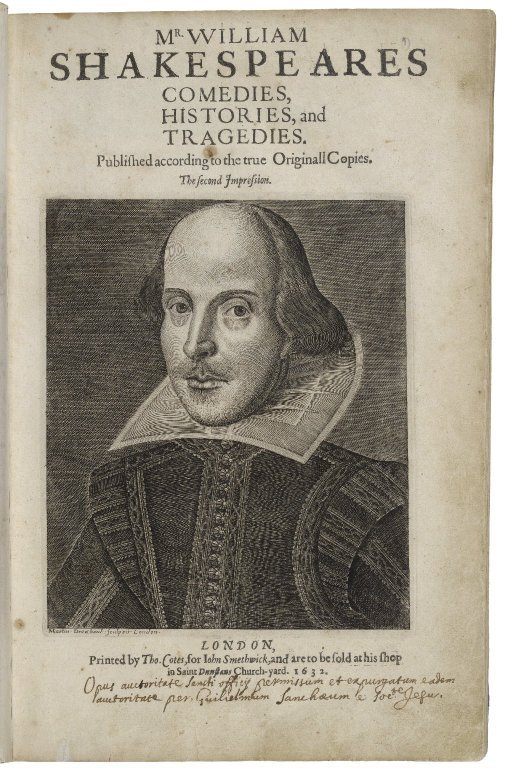

A 1632 edition of Shakespeare’s “Comedies, Histories and Tragedies”. (Photo: Folger Shakespeare Library/CC BY-SA 4.0)

There’s more to this than dick jokes, though. Shakespeare’s career took place on the tail end of the linguistic cataclysm known as the Great Vowel Shift, which transformed the pronunciation of the five long vowels of Middle English (phonetically /i:/, /e:/, /ɛː/, /a:/, /u:/, /o:/, /ɔː/) into the Modern English vowels we’re familiar with today. For instance, “bite” in 1350 would have been pronounced like “beet,” “mate” like “met,” and “out” like “oot.” (This is part of what makes Chaucer’s 14th-century Canterbury Tales so inaccessible to the modern reader.)

Even though the Great Vowel Shift was largely complete by 1600 or so, vowel pronunciation in Shakespeare’s time was still very much in flux. Samuel Johnson wouldn’t write his comprehensive English dictionary until 150 years later. In Elizabethan London, words still had no standard spellings, so they didn’t have standard pronunciations, either. What’s more, a flood of migrants from the countryside had brought with them their own idiosyncratic regional pronunciations.

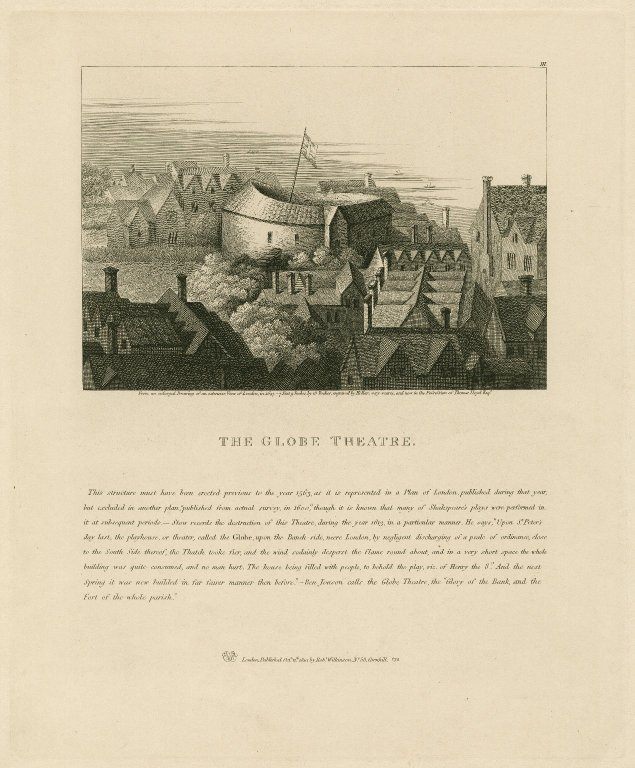

In his 2010 book Shakespeare and Language, professor Jonathan Hope argued that Elizabethans wouldn’t have acknowledged these regionalisms as “accents”—they were just part of the eclectic hodgepodge that was the English language at the time. (He points out, for instance, that Shakespeare’s stage directions only ever call for foreign accents like French and German, never regional English ones—as if those regional English accents didn’t exist.) That meant that performers at the Globe could pick and choose whatever regional pronunciations they felt worked best for a scene, sometimes mixing and matching them within a single sentence.

The Globe Theater. (Photo: Folger Shakespeare Library/CC BY-SA 4.0)

For instance, here’s a dirty pun on female fertility from Much Ado About Nothing. It plays off of “bairn,” a borrowed Scottish word for “child,” which at the time could have been pronounced as a homophone for “barn.” (It might also help to know that “stables,” as in “firm, erect,” is yet another boner reference.)

BEATRICE: Ye Light alove with your heeles, then if your husband have stables enough, you’ll look he shall lack no barns.

Some other dirty homophones you might have missed due to the fluidity of Elizabethan vowels, according to Kökeritz in Shakespeare’s Pronunciation: “neck” and “nick,” a slang term for vagina; “grace” and “grease,” which is a great pair for punning about the womanly virtues of greasy kitchen maids; and “pistol” and “pizzle,” or bull’s penis. It’s not necessarily that all of these would always have been pronounced as homophones—just that in Shakespeare’s time they could be pronounced that way. For the Bard, that was usually enough.

Beatrice, from Much Ado About Nothing. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London/CC BY-SA 4.0)

But this all raises the question: Why did Shakespeare load his work with so many puns—more, it turns out, than we even knew—when puns are inherently kind of silly?

Hope makes an interesting argument that it wasn’t just homophones that came across differently in Elizabethan times—the whole concept of a pun was different, too. Without standardized spelling or pronunciation, the meaning of any given sentence was a lot more ambiguous to an Elizabethan listener than it is for us today. A pun, then, was less about superficial wordplay and more about sorting out nuances in meaning—“active processes of disambiguation,” in Hope’s words. For Shakespeare, then, puns would have seemed more like their sophisticated cousins, the metaphor and the simile.

So maybe Samuel Johnson was wrong to cast aspersions on the humble pun. If you think like an Elizabethan, wordplay isn’t a distraction from the nuances of Shakespeare’s verse; it’s an enhancement. One that makes his plays both dirtier and more sophisticated than our modern minds could know.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook