When Physicians Used Lunar Signs to Diagnose Patients

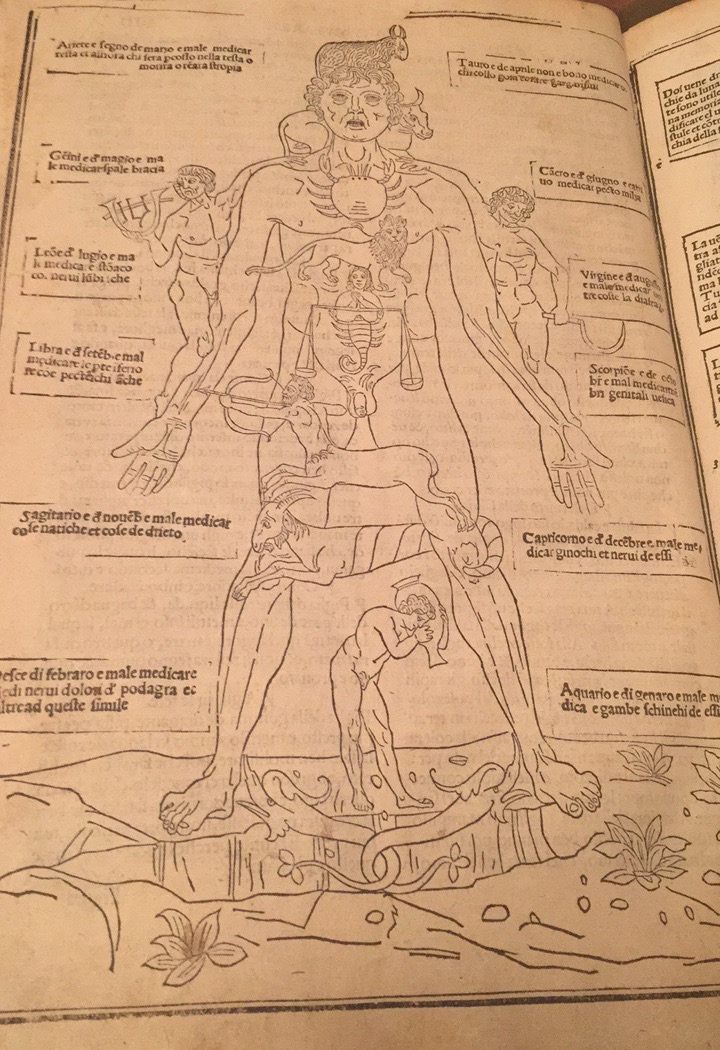

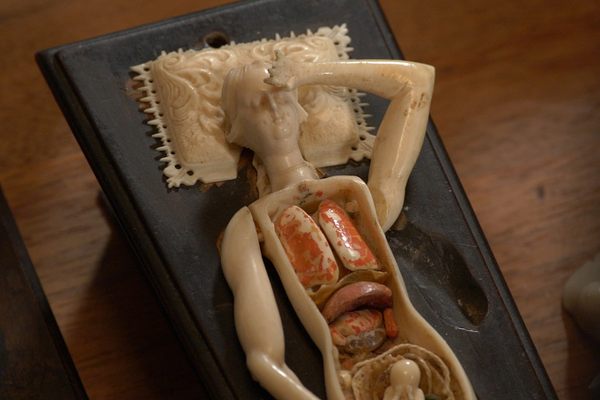

Meet the Zodiac Man.

In medieval Europe, bleeding was thought to be the most effective cure around. Medical practitioners believed no disease could withstand a nick in the neck from a small blade, otherwise known as a fleam. Have smallpox? No problem. Epilepsy? Easy. Gout? Cured.

But there was a catch.

Before operating on a patient, medieval physicians needed to consult the stars. The success of the procedure depended on it.

A foundational tenet of medieval medicine was the connection between astrology and human anatomy. The idea—which originated in Ancient Babylonian mythology—was that humans are microcosms of the Ptolemaic universe; the human body was divided into specific regions governed by Zodiac signs, analogous to the way the Earth was divided and ruled by planets.

The moon lay at the center of this theory. The moon’s alignment with a certain constellation signaled that a Zodiac sign was active—Libra, for instance, occurred when the moon blocked out the constellation Libra. Unlike their solar counterparts, lunar signs last only two or three days, rather than an entire month. (If you’re curious, you can find your moon sign here.)

In medieval medical theory, a lunar Zodiac sign corresponded to each human body part. Aries, for instance, governed the head and eyes; Taurus: the neck, shoulders, throat, and ears; Leo: the heart, spine, and spleen; and so on.

When a Zodiac sign was active, it was considered dangerous to operate on the associated body parts. Cutting into the neck during Taurus, for instance, could spell death. Because of these dangers, medieval physicians needed to pay special attention the stars.

To determine whether a Zodiac sign was active, they consulted volvelles, or rotating lunar calendars.

They then cross-referenced the active Zodiac sign with its corresponding body parts. To do this, they turned to the Zodiac Man.

The Zodiac Man is an illustration of the human body divided into twelve sections based on astrological signs. It guides physicians as to which body parts present a danger in which months. Before bleeding their patients—or performing any kind of medical operation—physicians relied on the Zodiac Man to tell them whether a body part could be safely cut.

The best-known rendition of the Zodiac Man is found in the Fasciculus medicinae, a popular medical book—and the first to feature anatomical sketches of the human body—that first appeared in Venice in 1491. Its printers attributed the work to “Johannes de Ketham,” likely in reference to the 15th-century professor of medicine and previous owner of some of the sketches, Johannes von Kirchheim.

According to an introduction by historian Charles Singer, the text’s “popularity was immediate and within eighteen months a new edition was required.” Subsequent editions were printed in Zaragoza in 1494, Pamplona in 1495, Sevilla in 1517, and in Venetia in 1495, 1500, 1501, 1508, 1514, and beyond.

Each edition of the Fasciculus medicinae features variations on the original illustrations (along with some new ones), which generally became more anatomically accurate with time. Singer writes that the 1491 version was “essentially a medieval product,” while the second edition demonstrated Italian Renaissance influences.

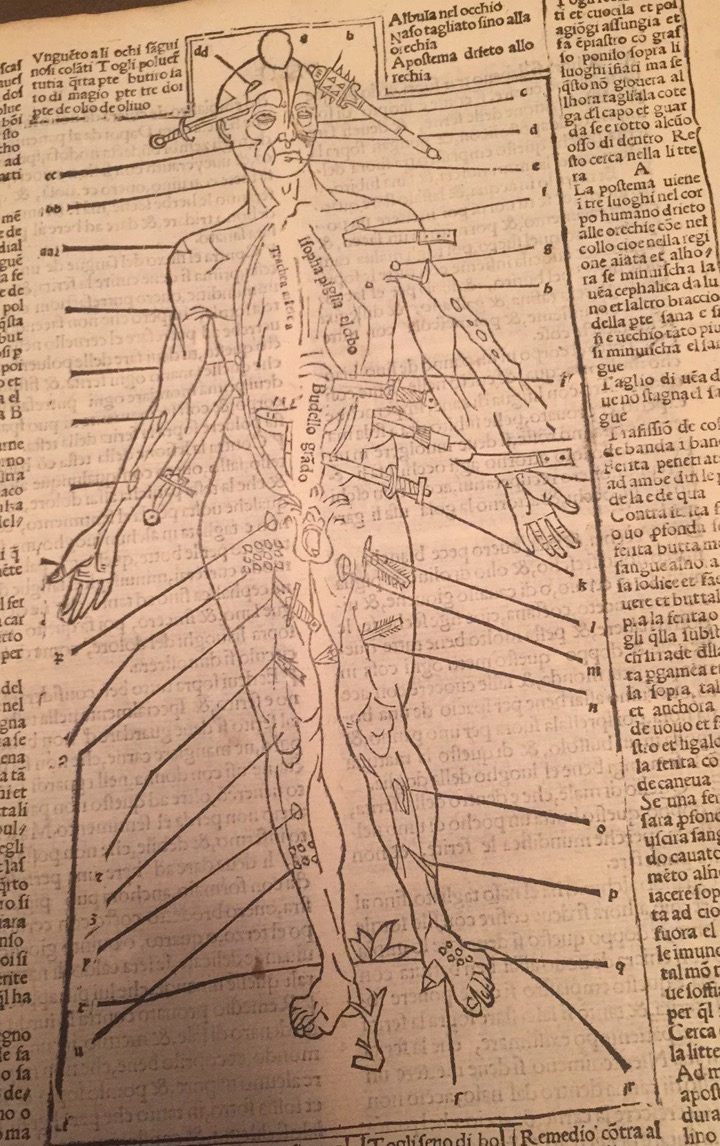

The Zodiac Man, too, changes from version to version. The New York Academy of Medicine holds an original 1522 edition from Venice. The images shown here are photographed from that edition. Alongside the Zodiac Man are several other woodcut illustrations, such as Wound Man, which warns surgeons of potential errors they could make during operations.

Underscoring the Fasciculus medicinae is the influence of the moon on medical practice. Lunar signs not only determined whether to operate on a particular body part; they also signaled the effectiveness of certain drugs. Herbs, too, were associated with specific Zodiac signs, and they only worked if they were gathered during the correct time period.

The moon even helped physicians make diagnoses. Diseases, it was believed, appeared cyclically with the alignment of the moon and the planets. The moon’s positioning with Jupiter often signaled the presence of liver disorders, while its alignment Venus usually triggered urinary problems.

You can see a version of the Fasciculus medicinae in its entirety here, and you can determine—per the Zodiac Man—which body parts your lunar sign puts at risk here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook