The Woolworth Building

Once the tallest building in the world and the site of "the highest dinner ever held in New York" this building now holds the most expensive penthouse in the city.

Frank Winfield Woolworth five-and-dimed his way to the top of the world, and he did it in style.

When the Woolworth Building opened in 1913, President Woodrow Wilson pressed a button in the White House, and 80,000 light bulbs flashed to life on Broadway as Thomas Edison supervised. Then Edison joined a banquet for 900 other prominent guests that the New-York Tribune called “the highest dinner ever held in New York.” During the ceremonies, famed radio pastor Samuel Parkes Cadman made “cathedral of commerce” the skyscraper’s nickname for the ages.

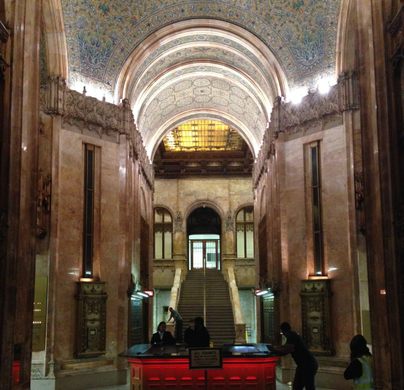

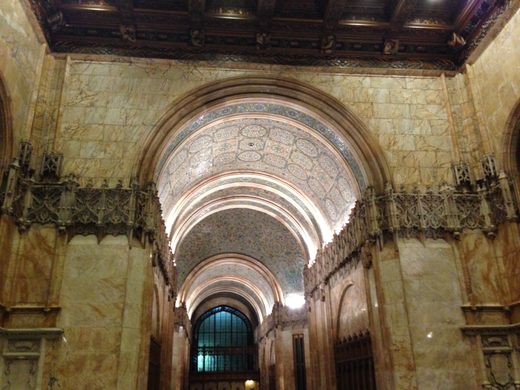

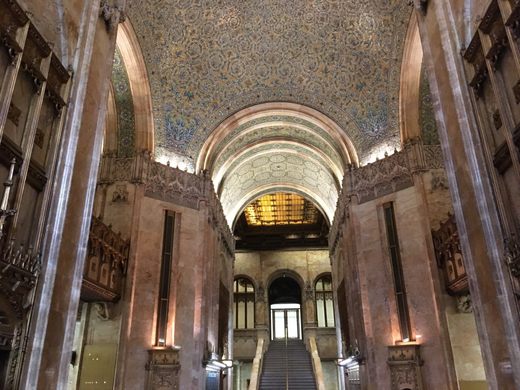

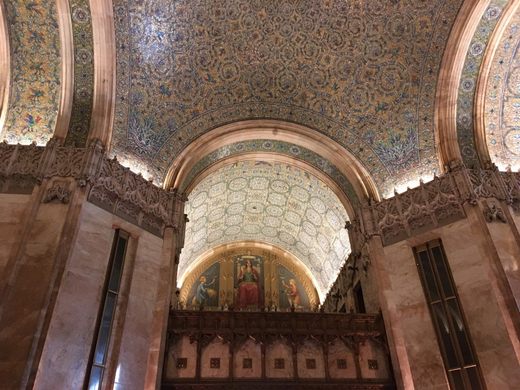

Over 100 years later, much of the original glory remains, though the general public wouldn’t know it. Master architect Cass Gilbert’s Gothic gem still gleams in lower Manhattan, but few tourists have been inside in recent years. The building’s owners for the past couple of decades closed it to casual visitors. Post-9/11 security restrictions didn’t help, either. But that’s starting to change.

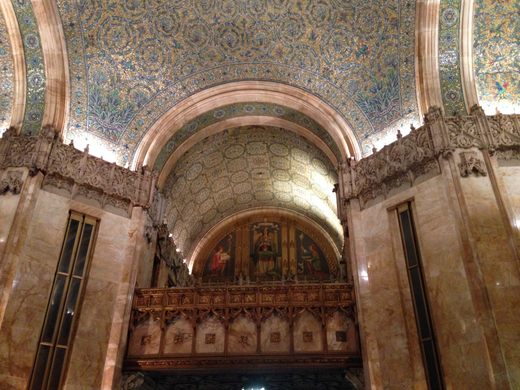

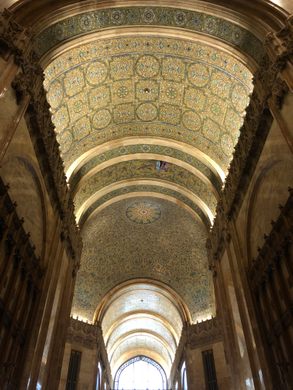

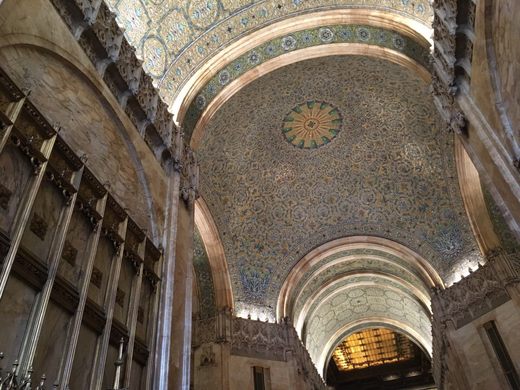

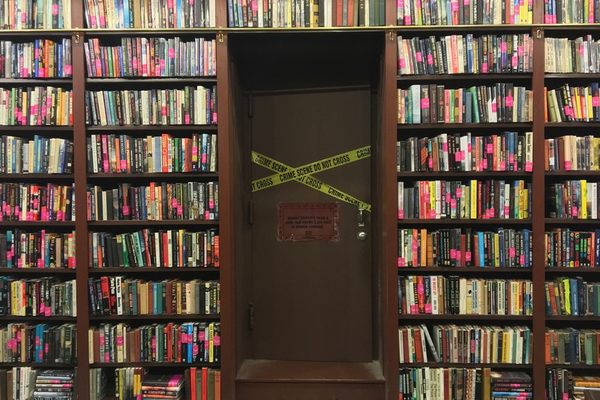

Thanks to the efforts of Gilbert’s great-granddaughter, Helen Post-Curry, the owners allowed private tours in 2013 for the building’s centennial celebration. A great response led to regular paid tours. The tours focus almost entirely on the lobby—in addition to the aforementioned unfortunate closures, the 57th-floor observation deck was shut down during World War II out of fear that enemy spies could exploit its harbor views—but the lobby contains plenty to illuminate the Woolworth’s soaring story.

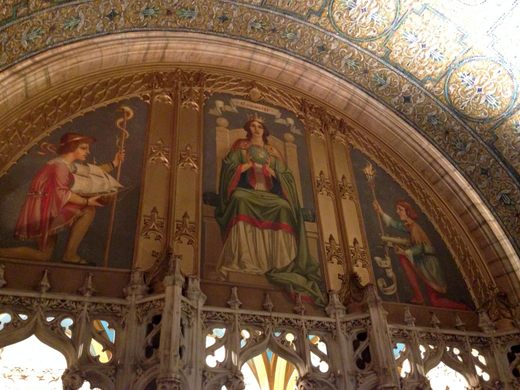

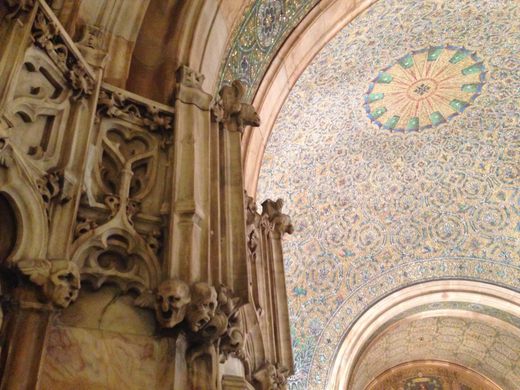

One need only look up at the grand Heinigke & Bowen stained-glass ceiling over the main stairs to grasp F.W. Woolworth’s animating vision. Border panels devoted to great empire-builders like Spain and Russia lie alongside others featuring the Woolworth “W” as well as 1913 for the building opening and 1879 for the opening of the first successful “Woolworth’s Great Five Cent Store” in Lancaster, Pennsylvania (a store in Utica, New York, failed in 1878, and Woolworth reused its sign in Lancaster).

By 1910, the operation was humming along well enough for Woolworth to lay plans for a company headquarters that would be the tallest building in the world, surpassing the 700-foot Metropolitan Life Insurance skyscraper completed in 1909. Woolworth scrapped a more modest $5 million estimate, and the final bill of $13.5 million produced the 792-foot (and one inch) finished structure of 58 stories (or 80 conventional stories, since ceilings range from 11 to 20 feet). The retail baron paid for it all in cash—perhaps in nickels and dimes only, as some say, and perhaps not.

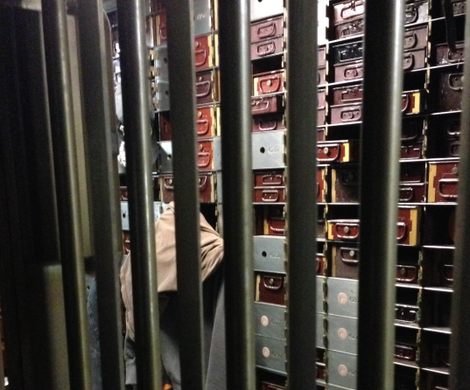

It’s also said that Woolworth spared no expense on the construction. Yet despite the gaudy price tag, he couldn’t resist a bit of skimping (amusingly enough, Woolworth is counting coins in the lobby gargoyle that portrays him). The Tiffany elevator ornamentation is cast iron done up like brass, terra cotta masquerades as marble on the exterior, and interior marble touted as “Greek” was actually mined in Vermont. Woolworth hired Cass Gilbert to create a world-class, historic company monument, but he always had business in mind.

“My idea was purely commercial,” he said in 1910. “I saw possibilities of making this the greatest income producing property in which I could invest my money.”

The building’s construction was a media phenomenon, and Woolworth was surely pleased with its critical reception and popularity. Woolworth opened his crown jewel up just like his stores, with counters and eateries alongside plentiful retail outlets. Missteps were minimal, such as the German beer hall shunned by some patriots during World War I, though the war’s drain on construction did benefit the building overall—it remained the world’s tallest until 1930, when the Chrysler Building and then the Empire State Building were completed.

The Woolworth Building finally left Woolworth hands in 1998 with a $155 million sale to the Witkoff Group, which launched a plan to turn the top 25 floors of the building tower into 34 luxury apartments. Most were offered for $7 to $10 million, though two listed at $20 million, and one seven-level “Castle in the Sky” penthouse had a city residential record $110 million price tag. The tower residences have a separate lobby and elevators as well as a restored lounge and an underground swimming pool.

One wonders what the building’s namesake would think of these investment returns, not to mention the stratification of a tower rooted in mass consumption. Woolworth pursued power and status relentlessly, though, and he enjoyed his lofty position from opulent personal spaces on various floors. These included a Renaissance-style apartment on the 40th floor, private suites on the 25th floor, and a 24th-floor “Empire Room” office inspired by Woolworth’s deep Napoleon obsession. Designers there used Napoleonic palace decor, filled it with memorabilia, and made a replica throne chair to await a man who saw his stores as an empire and his staff as a military hierarchy.

Unfortunately enough, Woolworth only reigned from what he called his “imperial capital” for about five years, dying at age 66 in 1919. If he were invited to the “Castle in the Sky,” he might marvel that his building is still breaking records and attracting the elite of a new gilded age. But perhaps he’d also insist on more foot traffic in the lobby.

Know Before You Go

The Woolworth Building is closed to the public, but tours of the building's lobby can be reserved online. Currently, prices range from $20 for a 30-minute tour, $30 for a 60-minute tour, and $45 for a 90-minute tour.

Community Contributors

Added by

Edited by

Plan Your Trip

The Atlas Obscura Podcast is Back!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook