How to Consult an Onion Oracle

From the Midwest to a tiny town in Italy, the tradition of weather-predicting onions lives on.

On a cold New Year’s Eve in 1967 in Ashley, North Dakota, newlyweds Donna and Delbert Eszlinger sliced excitedly into a large, round yellow onion. First, they split it lengthwise down the middle. Then, carefully, the couple peeled back the onion’s layers, laying 12 fresh, eye-watering sections side-by-side, and topping each with a teaspoon of salt.

The onion wasn’t the makings of a celebratory dish for the new year, but a window into the future. While the ground outside was still frozen, the couple looked to the onion layers to predict the coming year’s weather for their farm.

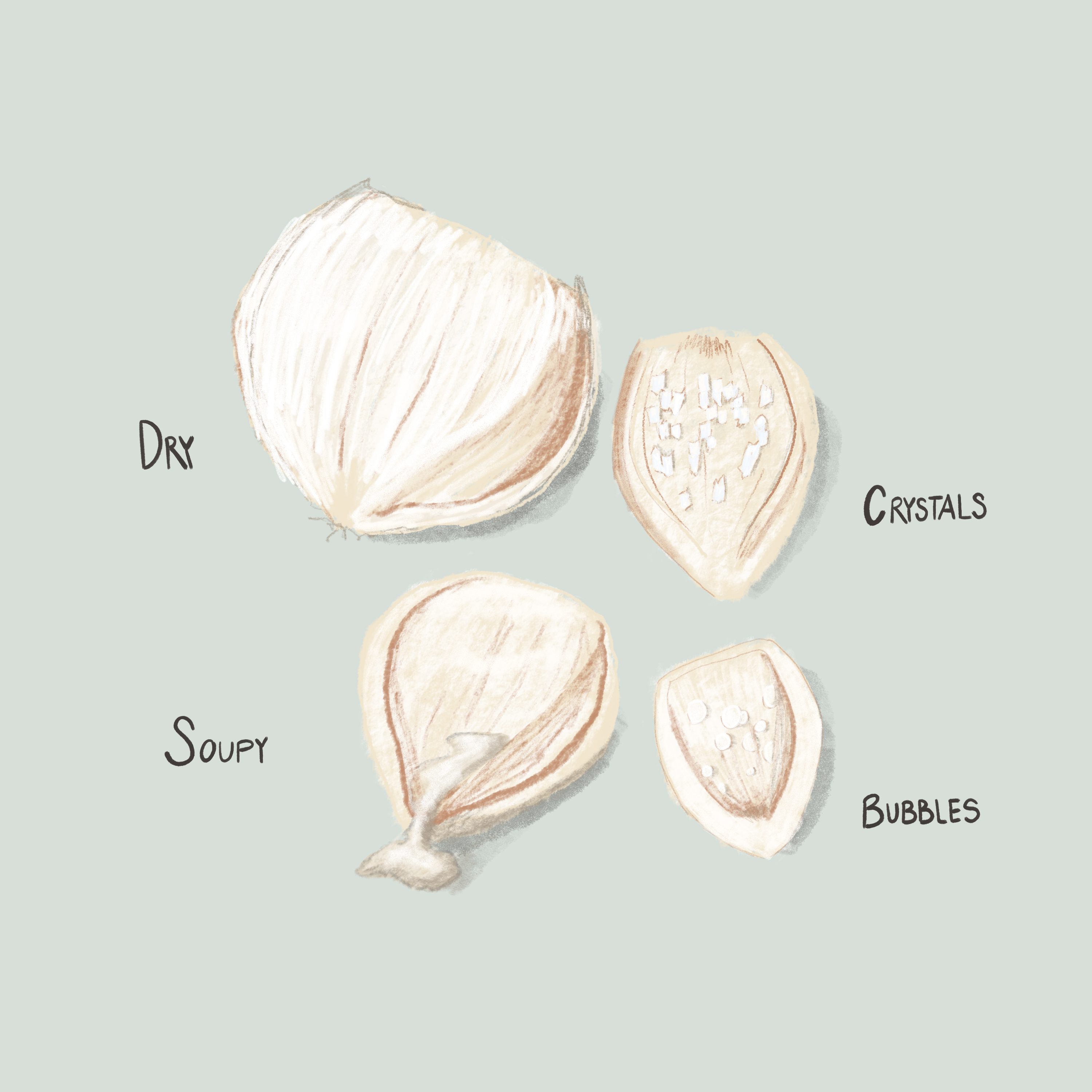

Early the next morning on New Year’s Day, the couple rose to check their results. How each onion slice reacted to the salt overnight foretold how wet or dry each month would be. They examined each piece in order—the first representing January’s precipitation, the second predicting February, and so on. Some pieces were left with dry salt, indicating a dry month, while the next might have a pool of briny liquid in its center, indicating heavy rains or snow. Caked or crusty salt crystals meant frost, and bubbles hinted at humidity.

The onion calendar, or onion oracle, dates back to the Middle Ages, when onions and other root vegetables were used by farmers to predict precipitation for the year ahead. Some of the oldest records of using onions as an oracle are from the small town of Urbania, Italy, where the tradition is still practiced today.

In Urbania, they do the ritual on the night of January 24, the eve of what’s known in the Catholic calendar as the Conversion of St. Paul, when the man named Saul was struck to the ground by a divine light and decided to become a Christian. Paul had received a sign of things to come on that night, so practitioners believed that the onion could best be read on the magical date. “He received a sign from God, he should be willing to give signs back,” says Elisa Luzi, an anthropologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany. Luzi is from a town near Urbania, and has studied onion oracles, earning her the local nickname “the onion girl.”

Consulting a vegetable about the long-term weather outlook seems quaint today, in an age of instant weather forecasts at our fingertips, but the tradition served its purpose in the past. “As humans, we sometimes fear the future,” says Luzi. “As a farmer, the weather can destroy an entire year of work. Having no control over rain or sun, you need to at least try and see what is coming.”

Luzi grew up with her grandparents who were farmers, and she remembers her grandmother saying casually, “What did the onion say for this month?” or “But the onion said that…” You can still hear the same questions around Urbania today, Luzi says.

“Some people believe it. Some do not,” she says. “It is kind of like a horoscope. Even if you don’t believe it, you still check it every now and then, just for fun.” The palm-sized weather predictors, which are cheap and readily available year-round, don’t enjoy any special status. “The next day, right after the reading, they become soup,” Luzi says.

While the tradition today is best known around Urbania, it can be found elsewhere as well. Australian farmer Halwyn ‘Hally’ Herrmann, for example, used the method for 65 years.

The practice can also be traced back to German folklore. In North Dakota, Delbert Eszlinger learned the ritual in childhood from neighbors who also farmed. The year the Eszlingers married, they decided to give the tradition a try—having continued it ever since. Donna Eszlinger says it usually works, with the exception of one reading several years ago. “It was such an odd year where the weather changed so often,” she says. “The whole onion was way off.”

The onion can be surprisingly specific, she adds. Three years ago, two pieces cut from the exact same outermost layer of the onion predicted opposite results for the months of January and July. “When we checked it the following morning, January had moisture and July had absolutely nothing,” says Eszlinger. “So what determines that there’s moisture in one and not at all in the other?” The contrasting results turned out to be right, she says. “We had a lot of snow that January, and then that July was very dry.”

In Ashley, even the local news has started following onion predictions—but not everyone is on board. “One time a weatherman on our local station caught wind of this and said, ‘Nobody knows the weather better than the weatherman,’” says Eszlinger with a laugh. “It was like he was a little put out that we were predicting the weather, like we’re taking away his job.”

“I think folklore forecasts will continue to reside in our social communities and circles. They’re tradition,” says Steve Ackerman, retired professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He adds tactfully: “While old sayings of the coming weather still enter our social lives, I do think we rely more now on forecasts that better reflect our understanding of atmosphere circulations.”

The Eszlingers appreciate science-based weather predictions and the convenience of the Weather Channel, but they still carry on the onion tradition—and Donna Eszingler hopes others will continue it after her. “The ones that are doing it, they’re the same age I am. I’m 75,” she says. “It’s a German thing and a heritage that we like to carry on.”

There are already signs that her two daughters are interested in continuing the many-layered tradition, she says. “They’ll call and say, ‘Okay, Mom, what are we going to have this year?’”

How to Make Your Own Calendar

The practice of making an onion calendar can vary slightly depending on what area you’re in, but the tradition goes something like this:

Step 1: Select a nice round onion. While the color and where it’s grown don’t matter, everyone has their preferences. The Eszlingers prefer yellow. “The yellow one seems to be a sturdier onion,” she says. “So you probably get a better reading that way.”

Step 2: Cut the onion in half lengthwise and carefully separate the six outermost layers so that you have 12 sections total. Lay the sections out in two rows: The first half should be January through June, with January being the outermost layer and June the innermost. The second half represents July (the outermost layer) through December (the innermost).

Step 3: Add a teaspoon of salt in the center of each onion cup.

Step 4: Let sit overnight. Some people keep it inside, but many agree it should be outside to get the most accurate reading.

Step 5: In the early morning—ideally around 5 a.m.—bring the onion inside and quickly jot down your readings before the inside temperatures change the results.

Step 6: Enjoy consulting your onion calendar throughout the year!

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook