How to Explore West Virginia’s Underground Wonders

A field guide to the most invigorating subterranean adventures in the Mountain State

How often do you really stop to think about what’s beneath your feet? In West Virginia, the wild world below is full of incredible experiences that provide a glimpse into the ancient landscapes, indigenous heritage, key industries, and down-right grit that encompass the state’s collective character. You just have to dig below the surface.

Of course, the Mountain State is well known for its stunning Appalachian landscapes, rushing rivers, epic gorges, and song-worthy country roads. But below all that lies a wondrous world of sprawling caves, once-secret military bunkers, historic salt mines steeped in family heritage, and relaxing salt caves – all ready for you to explore.

The Bunker at The Greenbrier

Uncover a Government Secret

In the 1960s, the U.S. and Russia were in a nuclear arms race, and the potential for an attack on American soil was the era’s greatest threat. The government needed a plan: a secret fallout bunker that would protect Congress in the event of a strike. They called the mission “Project Greek Island,” and they built it in West Virginia.

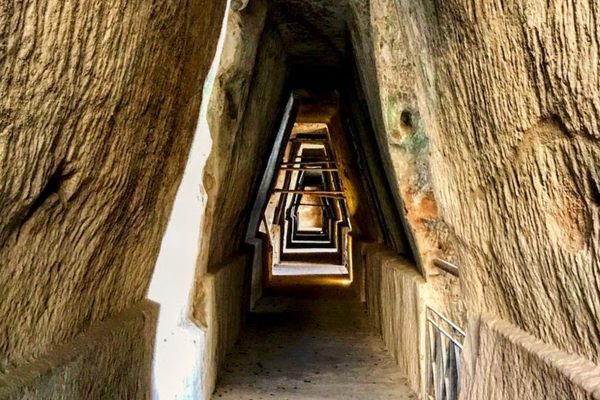

Burrowed deep in the hills of White Sulphur Springs, under the luxurious veil of the Greenbrier Resort, external signs that read, “Danger, High Voltage!” were intended to keep curious outsiders from asking questions.

The 112,544-square-foot bunker was built roughly 700 feet into the hillside, simple and functional in design. In the underground labyrinth today, you’ll still find the simple cots, hospital, meeting rooms, and intensive care unit in the same condition they were in during the heart of the Cold War.

Nuclear, biological, and chemical filters on the air system, they surmised, would make it safe to breathe. “There was a 60 day food supply, 45 days of diesel fuel for alternative power, and 72 hours of air when it was sealed shut,” said bunker manager Deanna Hylton, who’s been a guide for 18 years. “The thought was that the fallout would settle to the ground, and the air vents would be opened to let the fresh air back in.”

But no secret lasts forever. In 1992, though it had been maintained in a pristine state of readiness for 30 years, the bunker was decommissioned after a Washington Post story uncovered its existence.

Of course, the government never put the bunker to the test. “If they did, it would no longer have been a secret,” said Hylton. “It was never used for the purpose it was created, so we will never know if the plan would have worked.”

J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works

How to Harvest Your Own Salt

In West Virginia, salt mining is as old as America itself. In 1797, in the Kanawha Valley near the capital city of Charleston, the state’s first salt furnace was built. The salt dates back about 500 million years, to a time when it was trapped deep below the Appalachian Mountains by one of the earth’s first oceans.

The ancient Iapetus Ocean is where the Pangea formed, before the continents split. When the continents as we know them today split apart, each took part of the ocean, and salt deposits ended up below the Appalachian range. Over time, they were redissolved by a freshwater aquifer, leaving a salty river, or brine, below the Dickinson family farm.

By 1819, the Dickinsons started mining the brine, and for the next 125 years, they harvested it from their Malden farm. Siblings Nancy Bruns and Lewis Payne resurrected the family business in 2013. Using vintage family maps and well logs, the pair centered on a specific part of the land and started drilling.

During harvest season, which usually begins in April and runs through October or November at J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works, you can walk in the shoes of these early practitioners and harvest your own small-batch salt.

The process, though complex, is organic. The brine is drawn to the surface from 350 feet below ground by a water well pump and fed into sun houses onto tables lined with food-grade plastic. The brine stays there until it evaporates to a salinity level of 15 percent. Staff members then move it to a greenhouse, where it crystallizes. Once crystallized, they harvest it by hand. The result is the perfect finishing salt for a juicy ribeye or roasted root vegetables.

“Continuing this legacy as a seventh generation native of the Kanawha Valley is a gift,” said Bruns. “The best part is the difference we are making in Appalachia. We partner with other producers and makers to share the high-quality products…while keeping the local economy humming.”

Lost World Caverns

Find Inspiration Underground

In 1942, a discovery unlike any other took place far below the West Virginia soil. Like a wild world in a Tolkien novel, Lost World Caverns feels like another dimension, hundreds of feet deep, cast in shadows and filled with incredible ochre-colored twists and turns.

The cavern was discovered when university researchers decided to explore a deep sinkhole where, for years, farmers had tossed animal parts and other garbage. Originally named the “Grapevine Cavern,” geologists now call the cavern a “karst plateau,” a broad limestone tableland, chemically eroded by water into meandering, holey passages.

The main chamber itself is a vaulted masterpiece. At over 1000 feet long, 300 feet wide, and 120 feet tall, its size is roughly twice that of Notre Dame’s interior. The cave is also the site of a unique feat: In 1971, former cave manager Bob Addis sat upon the towering, 26-foot high “War Club” stalagmite for just shy of 16 days, landing himself in the Guinness Book of World Records.

Inside, it’s a cool 52 degrees, so pack your jacket, lace up your shoes, and take the half-mile walking tour to discover unreal formations like the 30-ton “Snowy Chandelier,” one of the world’s largest compound stalactites, and a column of white calcite known as “Bridal Veil.”

Smoke Hole Caverns

Scratch Beneath the Surface

On the banks of a river in the Spruce Knob-Seneca Rocks National Recreation Area, you’ll find a deep-down location that’s steeped in the land’s indigenous history. Smoke Hole Caverns gets its name from the clouds of smoke that traveled through the valley as the Native Seneca people smoked wild game inside these caverns.

Following the Civil War, the discreet confines of the caverns served another purpose: making moonshine. An original still remains on display today. Above ground, Smoke Hole offers a grand log-cabin lodge, cozy cabin rentals for couples or families, plus a trout pond, gift shop, and more.

Exhibition Coal Mine

Roll Through a Coal Mine

The salt mining industry in West Virginia created a great need for one thing: coal. By 1840, nearly 100 furnaces produced 1 million bushels of salt a year. But heating the furnaces required coal, and a lot of it.

In Beckley, West Virginia, in a park along the river, you’ll find an Exhibition Coal Mine. From April to November, you can hop in a 35-person “man ride” – small connected carts that carried the workers in and out of the mine – and snake through dark and damp passageways. Roll past wooden-beam structures and exposed rock on either side of the narrow route as veteran miners share personal accounts of their lives below.

The Pomona Salt Cave and Spa

Soak in the Salt

Leave your smartphone behind and remove yourself from external stimuli as you enter a state of calm at the Pomona Salt Cave & Spa in White Sulphur Springs. Made of over 18,000 pounds of Himalayan salt, the cave offers a negative ion experience, which research has shown can reduce symptoms of depression, enhance cognitive function, increase immunity, and more.

While comfortably seated, you’ll be surrounded by ruggedly beautiful natural elements. Simply relax, or opt for one of the add-on experiences, like sound therapy, an ancient healing remedy that uses traditional percussion instruments like Tibetan singing bowls and gongs to help achieve greater relaxation and even reduce physical pain.

Hidden below ground, West Virginia shares a storied network of the people, industries, and heritage that keeps curious travelers coming back for more. Now, dig in and choose your own underground adventure.

Sponsored by the West Virginia Department of Tourism. Learn more and plan your trip at wvtourism.com

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook