A Traditional Globe Maker is Making 3-D Versions of Historic Martian Maps

This German company specializes in planetary spheres based on antique maps.

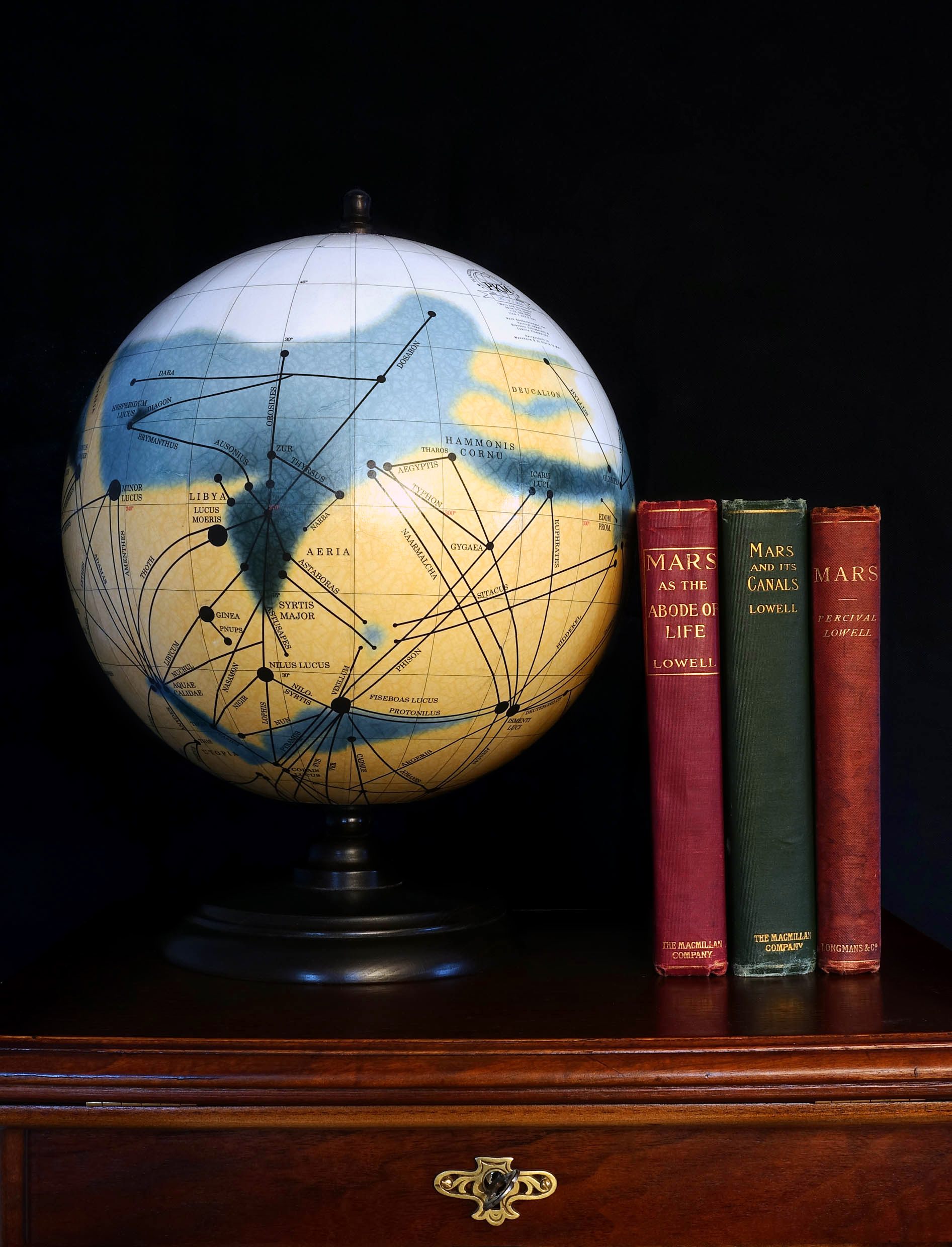

Percival Lowell’s Martian canals map may have been troubling in the 19th century, but it now serves as a stunning piece in Michael Plichta’s globe manufacturing studio. [All Photos: Michael Martin Plichta/Planetenkugel-Manufaktur]

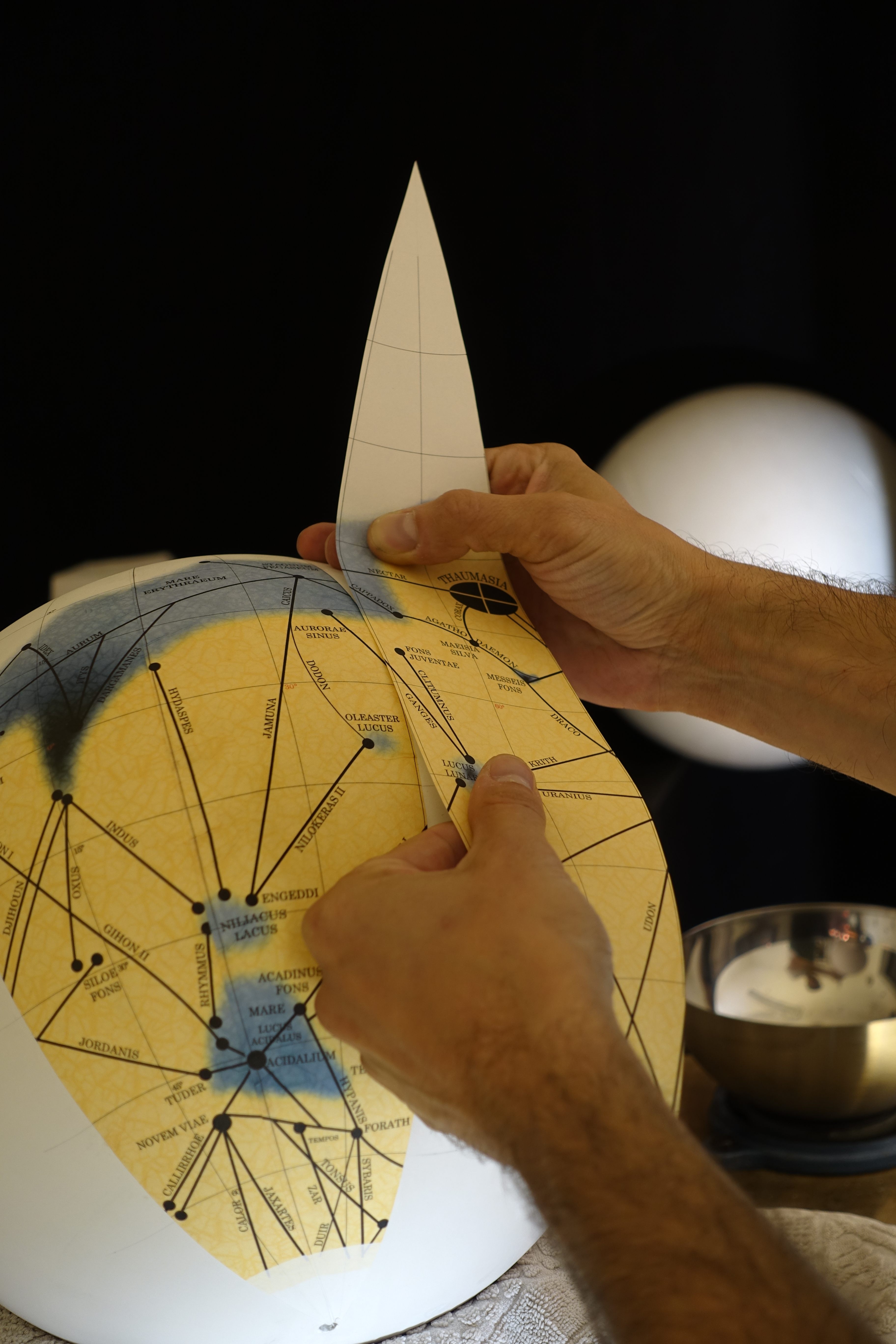

In a workshop in Mannheim, Germany, Michael Plichta carefully and slowly aligns paper gores, or segments, by hand onto a globe of Mars. But the topography reflected on this replication of the Red Planet isn’t one based on the sophisticated data and satellite imagery collected by NASA.

Instead, Plichta’s collection of globes uses astronomer Percival Lowell’s strange and controversial maps charting Martian canals as their template. The 19th century astronomer and his Martian canals theory were the topics of high controversy and mockery among astronomy scholars between the late-1800s to early-1900s, flaring up debates about signs of intelligent life on Mars.

“The map basically looks like a spider’s web spun around a sphere,” says Plichta, who is one of the last remaining traditional globe makers.

Applying one paper gore takes Plichta about one hour. It’s the most difficult step in the globe making process.

Applying one paper gore takes Plichta about one hour. It’s the most difficult step in the globe making process.The spinning, three-dimensional maps produced at Plichta’s globe manufactory, Planetenkugel-Manufaktur, are not of the planet we inhabit, but of other worlds in our solar system. For his globes, Plichta seeks out historical planetary maps that modern astronomy has deemed defunct—the globes providing a new perspective on old observations. Then, he painstakingly fashions these maps into globes with traditional techniques that required over two years for him to master.

Plichta, a senior scientist and trained psychologist at the Central Institute of Mental Health in Zurich, Switzerland, describes himself as an amateur astronomer. At the age of 15, he began peering at celestial bodies from his telescope. He was most fascinated by the surface of Mars, impressed by the polar ice caps and dark blue-green splotches contrasting against a reddish ochre backdrop.

Traditional globe making requires a stead hand.

Traditional globe making requires a stead hand.

He started making globes in 2014 after finding a 1960 globe of the moon—part of which was blank because satellite information had yet to be obtained. Curious about what old astronomical observations might reveal when turned into a 3-D form, he decided to make this Planetenkugel-Manufaktur’s unique specialty.

“Since distances in space are so large, our imagination often fills the gaps in knowledge,” Plichta says. “Lowell described in his famous book, Mars and Its Canals, that when he was observing Mars with his telescope, he felt like he was traveling without moving.”

A copy of Percival Lowell’s mars canal map that Plichta uses for his globes.

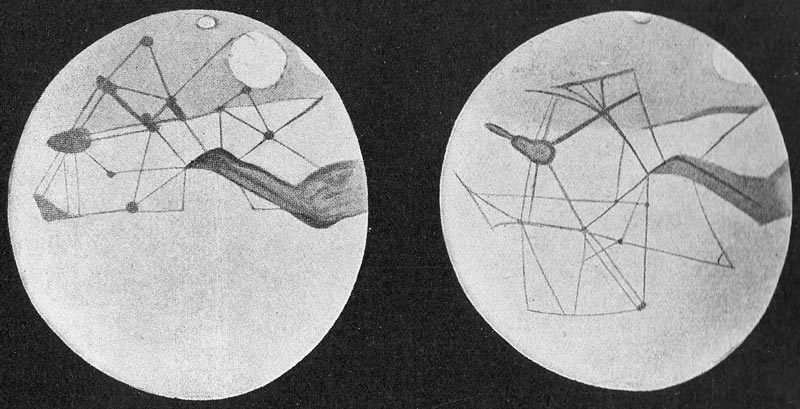

The story of the Martian canals begins with Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, who first observed a series of lines he called “canali” on the surface of Mars. He published a map of his findings in 1878, and marked the lines as geological features. After analyzing Schiaparelli’s maps and making his own observations of Mars, Lowell thought that the directions and positions of the lines were too intentional to be valleys or mountain ranges.

“For Lowell, it was clear that the canals couldn’t be natural features,” explains Plichta.

The canals were long straight lines, sometimes two running parallel to each other. Lowell declared that the canals were a part of a complex irrigation system that could have only been built by an intelligent, ancient civilization on the brink of extinction. He believed that when the polar caps melted, the canals carried water to other parts of the dry, dying Red Planet.

Percival Lowell’s Martian canals. [Photo: Public Domain]

Percival Lowell’s Martian canals. [Photo: Public Domain]By the end of his life, Lowell had charted and identified over 700 canals, his map showing the vast cobweb of straight black lines crisscrossing over the entire planet. He even gave mythological names to each of the canals, such as Agathodaemon, Eumenides, and Orcus.

The maps were attacked by other professional astronomers who didn’t observe the canals, but Lowell was still convinced that his charted cartography of Mars was correct. We know today that Lowell’s Mars canal theory holds no merit.

NASA’s Mariner mission in 1965 took close-up photos of Mars, and in 1972 was able to map the planet, reports Space.com. No canals were found. Scientists now believe that the lines that Lowell and Schiaparelli saw were an optical illusion caused by the telescopes.

Inside Plichta’s studio in Mannheim, Germany.

Inside Plichta’s studio in Mannheim, Germany. Plichta realized he couldn’t find a globe of the infamous map from Lowell’s book Mars and Its Canals, and decided to make it his first project. He turned to antiquarian books about globes and globe makers, and used the 1960 moon globe as his guide.

Plichta creates his Mars globes in a traditional manner by first shaping a sphere out of plaster of Paris with a high-precision, metal-revolving machine. He then uses a compass to draw the orientation lines onto the sphere to guide him as he places the paper gores pieces by piece. Gently brushing special glue, he flattens the football-shaped clipping of the map onto the surface.

Plichta carefully inspecting the shape of a plaster sphere.

Plichta carefully inspecting the shape of a plaster sphere.

“You have to be very precise here, since every error is multiplied by Pi,” Plichta explains, since the spherical shape requires constant re-measuring for the pieces of the map to fit on the globe. “I have practiced this step over and over again.”

Applying one paper gore takes about one hour. After placing all 12 to 24 onto the globe, he positions the polar caps, varnishes the sphere, and mounts it. The whole process for one globe takes about six to eight weeks, he says. The finished product is a stunning cream and turquoise sphere ornately detailed with all of Lowell’s black canal etchings.

Depending on the size, a globe requires 12 or 24 paper gores.

Depending on the size, a globe requires 12 or 24 paper gores.

“The Mars canal globe shows interesting phenomena that cannot be easily inferred from the 2-D map,” Plichta says. “Straight lines on a 2-D map are curved on a sphere. The globe shows that the canals are mostly the shortest connections between two points of the sphere.”

Plichta continues to add to his historical planetary globe collection. He is currently planning out a globe of Venus using a small globe that Vatican employee Francesco Bianchini made in 1728, and a moon relief globe, which will show the shadows, craters, and hills in a realistic view. Plichta will showcase his latest creation in an exhibition in Germany this fall.

The finished product, one of many different kinds of historical planetary globes to come.

The finished product, one of many different kinds of historical planetary globes to come.Customers have also commissioned Plichta to create fictional planets, Flash Gordon’s Mongo and author Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom, a romanticized version of a dying Mars. To his knowledge, his business is the only one that specializes in handmade planetary spheres based on past maps and observations.

“Historically, a globe has always been a sign of power and it encapsulates the knowledge of mankind about the earth and space,” Plichta says. “As long as humans explore their surroundings and add fantasy and imagination, I am sure to have enough material to build more fantastic worlds at the borderline between science and fiction.”

Map Monday highlights interesting and unusual cartographic pursuits from around the world and through time. Read more Map Monday posts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook