Rediscovering the Blazingly Bright Colors of Ancient Sculptures

And why most of us grew up believing classical sculpture is white.

In 1811, a group of English and German scholars happened upon the Aphaia Temple, on the Aegina Island, in Greece. The temple dated from around 500 BC, and despite the centuries that had passed, at the time the site still held the remains of marble sculptures from the temple’s east and west pediments. These figures depicted scenes of the Trojan wars, and although weathered and partly broken, they also contained an intriguing detail: visible signs of red and blue paint.

In 2006, the German archaeologists Vinzenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann examined one of these figures more closely, using raking light and ultra-violet photography. What they found was that the Aphaia’s Trojan archer, crouched low, bow taut and barefoot, was actually once painted in an array of colors, from his cap to his feet. Patterns of diamonds, animals, and zigzags adorned his clothes. In his painted hands—believed to be a mixture of rose madder and red ochre—he held a golden bow. (The original sculptures are still on display at the Glyptothek Museum in Munich; as with the Parthenon before it, artifacts from the Aphaia Temple were plundered and sold).

“We’re so used to seeing—because of museums, because of plaster casts, because of the way sculpture has come down to us—[classical sculptures] denuded of any color,” says Renée Dreyfus, Curator of Ancient Art and Interpretation at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, where she curated the recent exhibition Gods in Color: Polychromy in the Ancient World. Variations of this exhibition have been on display at a number of museums since 2003, and all of them are based on vibrant reconstructions of how the ancient world would have actually looked. Now, there is also a book, edited by Dreyfus, Brinkmann and Koch-Brinkmann, of the same name.

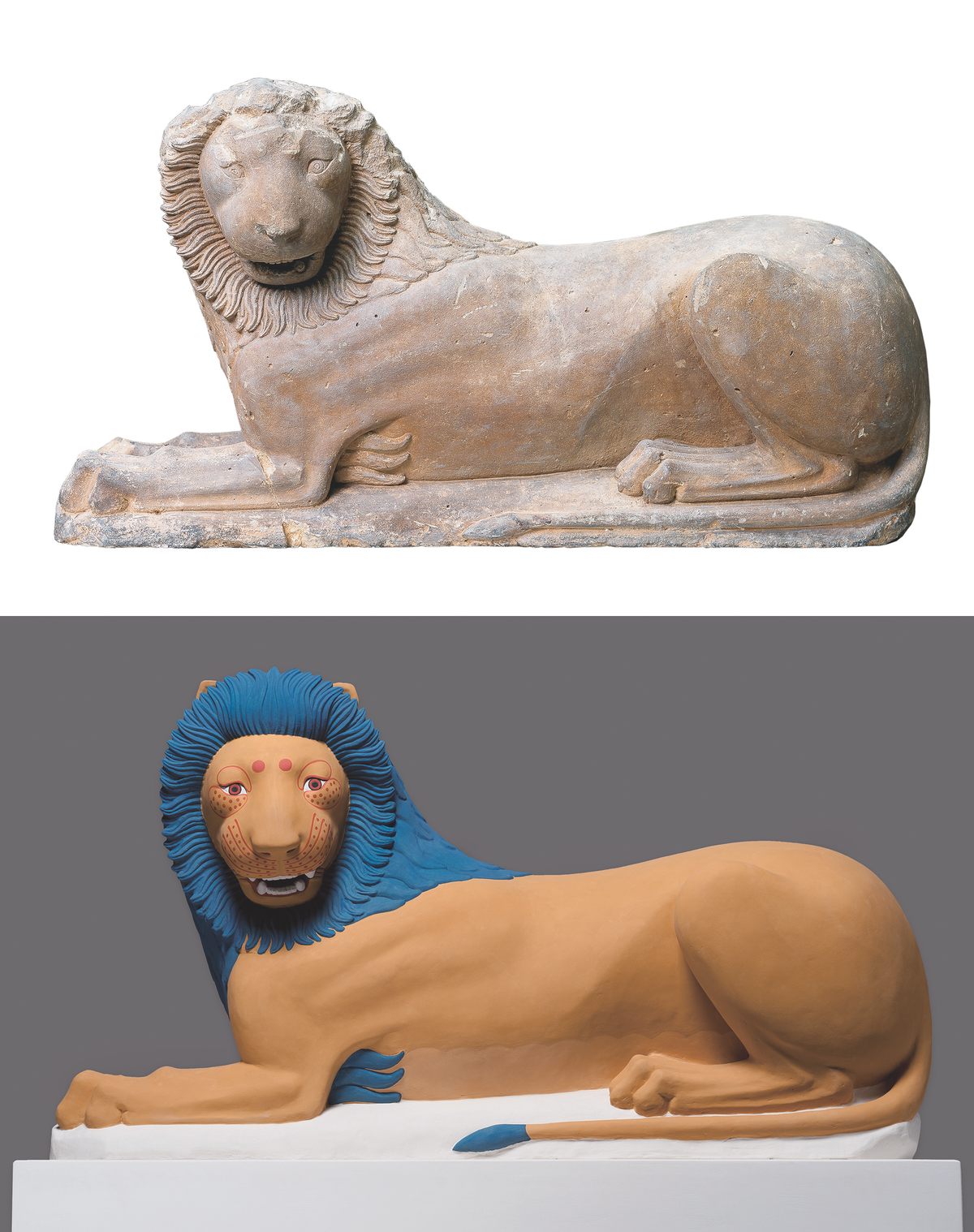

Polychromy—painting sculpture or architecture with color—was widespread in antiquity, and the reconstructions presented in the exhibition and book present a very different vision to the white marble statues that silently adorn the classical galleries of museums around the world.

As classical art was rediscovered during the Renaissance, Dreyfus says, it was not always possible to see the traces of paint. In some instances, after being unearthed, sculptures were “scrubbed clean.” With the excavation of the neighborhoods around Pompeii, however, more solid examples of polychromy were discovered. “Anything from Pompeii was well preserved because it was covered in ash,” explains Dreyfus.

Further examples followed. In 1805, the British scholar Edward Dodwell and the Italian painter Simone Pomardi traveled to Greece. There, they observed faded color on the Parthenon and the Erechtheion. The paintings that both Dodwell and Pomari created show vestiges of paint on both sculpture and architecture, and “are really wonderful at documenting what the monuments originally looked like. They were seeing it in 1805, and it’s astounding how much more color they had in 1805 than they do today,” says Dreyfus.

At the time of his trip, Dodwell observed:

Besides the custom of painting statues, the ancients had various other methods of enriching their appearance; most of which are irreconcilable with our ideas of beauty or congruity. Some were gilded; many of them had eyes composed of coloured stones, gems or glass.

And yet the idea of all-white marble classical sculpture continued to dominate. This misconception can be traced to the 18th-century art historian Johann Joachim Wincklemann. Although Wincklemann recognized that color was in use in antiquity, he diminished its importance. “What he really waxes poetic about—and people read his work—was the form. And the form seems to have taken on more of an emphasis,” says Dreyfus.

Wincklemann also clearly revered the whiteness of the stone, writing, in 1764: “Colour contributes to beauty, but it is not beauty itself, though it generally enhances beauty and its forms. Since white is the colour that reflects the most rays of light, and thus is most easily perceived, a beautiful body will be all the more beautiful the whiter it is, and nude it will thereby appear larger than it actually is… .” It’s notable here, as some critics argue, that Wincklemann not only downplayed the importance of polychromy, but at the same time promoted whiteness as an ideal.

Such was Wincklemann’s influence that, despite the evidence, polychromy continued to be debated throughout the 19th century. It wasn’t until the 1960s that classical sculptures began to be examined with ultra-violet photography; today, technologies such as “x-ray luminescence, for example, fluorescence, the ultra-violet and infra-red light,” says Dreyfus, can clearly examine the details contained in ancient, faded pigment.

And it’s these precise details that inform such dazzling reconstructions. From the Acropolis, the figure of Chios Kore wears a garment of bright blue and red with a yellow cloak, with braided hair painted yellow-ochre. From the same site, a breastplate is reimagined in gold leaf, surrounded by a pattern of leaves. But it was not only marble and stone that was painted.

In 1972, two bronze statues were hauled from the sea off the coast of Calabria, Italy. They revealed extraordinary details: their eyes were cast from stones of different colors; their mouths were moulded from copper; and the teeth of Warrior A were made from silver relief. By analyzing sulphur residue, Brinkmann and his team could hypothesize on the skin and hair of the original bronzes. These figures were also reconstructed. “They used 3D modeling to create the mold and then actually cast them in bronze,” says Dreyfus. “On the original they had copper eyelashes, copper lips, copper nipples, the eyes were inlaid with stone … you could even see the different colors the bronze had been treated in the originals for an older and a younger man.”

These reconstructions allow us to glimpse how the streets and buildings of antiquity might have actually looked. And, while Dreyfus notes that classical art and architecture was repainted over time, “we also know their idea of the perfect sculpture is the one that duplicates reality the best,” she says. “So if you look around you and the world is in bright living color, statues would also have to be in color.”

AO has a selection of images from the book.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook