When Ancient Writing Is an Art, Science, and Snack

If you’re going to practice writing cuneiform, why not do it on a cookie?

Scholars who study cuneiform and other ancient writing systems might spend much of their careers scrutinizing photographs or reproductions, since the original tablets are enshrined in museums. To get further insight into how these ancient objects were created and can be interpreted, some also practice recreating inscriptions themselves. Air-drying clay and plasticine are common mediums, but some scholars, including researchers at University of Cambridge, have been using a sweeter alternative—cookie dough.

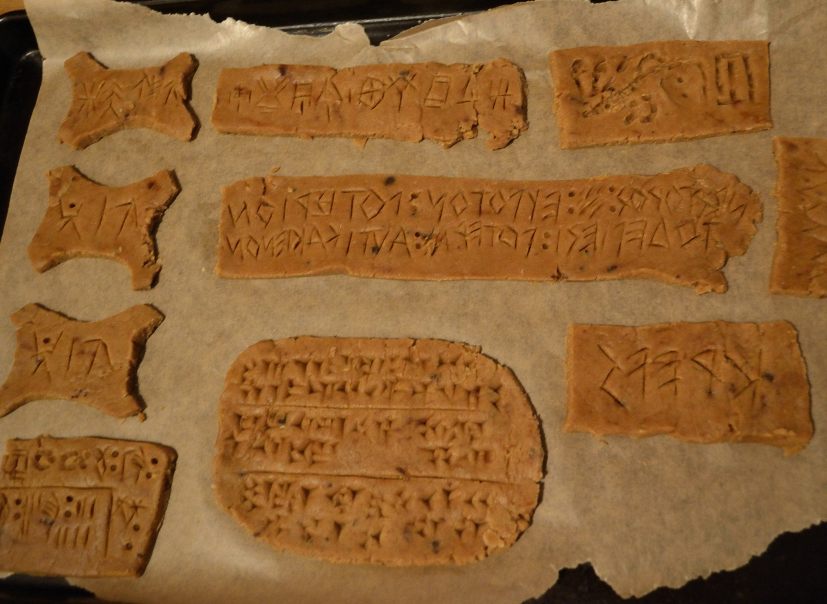

“Working on languages, it’s a fairly obvious thing to try at least once,” says Philip Boyes, a postdoctoral researcher who works on the Contexts of and Relations Between Early Writing Systems (CREWS) project. Last month, he made a deliciously nerdy cooking video chronicling his experience printing Ugaritic cuneiform on a batch of speculoos cookies.

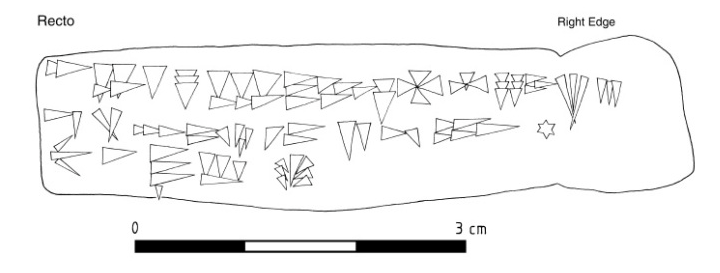

Ugaritic, which was used in what is now Syria around 1400 B.C., simplified the hundreds of signs of Mesopotamian cuneiform to an alphabet with just 30 symbols. Thousands of Ugaritic tablets have survived, and describe religion, medicine, economics, and more.

Boyes comes to the study of the language from archaeology—rather than linguistics or epigraphy—so his work digs into cultural practices around writing, including how scribes learned and what commonly tripped them up. Practice has a lot to teach him. “Traditionally, a lot of linguistic research has been divorced from archaeological research,” he says. It’s easy to think of these texts as symbols—“floating, like letters on a screen almost”—and not objects that have heft and dimension, he adds. Most of the surviving Ugaritic tablets are kept in France and Syria. Until Boyes makes a research trip to the Louvre, he’s trying to better understand the unique problems of crafting and deciphering these texts.

For his cooking video, Boyes made a batch of speculoos cookies spiced with cardamom, cinnamon, nutmeg, and ginger. He chose these cookies in particular because “the dough holds an impression,” he says, and doesn’t distort as it bakes. Also, he adds, “because I happen to like them.” After a previous attempt with a stylus he made from Legos, Boyes has successfully enlisted the square end of a chopstick as his writing implement.

Boyes printed the Ugaritic alphabet on his cookies, which probably would have been a practice exercise for scribes-in-training. These students might have practiced on tablets just a couple of inches long, while the cookie Boyes used is roughly as wide as a sheet of paper. Reproductions of cuneiform tablets in books sometimes belie the scale of the originals—some cuneiform writing is really, really small. “Think about reading these tiny indentations in clay in a place with no artificial light,” Boyes says. “It’s hard enough to read with a magnifying glass.” So he scaled them up. Enlarging the size “makes it much easier to write, and it’s a nice-sized biscuit,” he says in the how-to.

Boyes stresses that he’s still learning, and he’s not striving for total fidelity to ancient technique. “What I’ve been doing is largely for my own education, and for outreach purposes to get people involved,” he says. “I’m less concerned with getting it absolutely accurate.” At least the results tasted good.

Students and researchers have experimented with edible cuneiform for years. Katherine Blanchard, keeper of collections in the Near East department of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, made a batch in 2014. She explained to The Forward that while she works with the tablets, she doesn’t try to decipher the language. The goal wasn’t to practice spelling out a specific text, but to emphasize to curious eaters “that a dead language was still part of my life, and now it was part of theirs.”

The following year, Esther Brownsmith, a doctoral candidate at Brandeis University, ran with the idea and inscribed passages from the epic Babylonian myth Enûma Eliš onto sheets of gingerbread on the Tumblr “Slightly Alive Translations.” The cookies doubled as a way to coax students to come to office hours, Brownsmith told the New York Times. “So cuneiform cookies seemed like a great way to feed them while also giving a tangible link to the subject of Gilgamesh.” Maybe the way to the brain is through the stomach.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook