The Ambitious Plan to Digitize 100,000 Historic Texts in Belgium

Two major Antwerp institutions are putting some of their voluminous holdings in the cloud.

Come September, a fleet of secure vehicles will pull up to a 17th-century building in Antwerp, Belgium, receive cases full of heavily protected cargo, and then abscond with the goods to a confidential location. The booty? Five thousand rare, centuries-old books, on their way to a 21st-century treatment.

Recently, the Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library and the Plantin-Moretus Museum, both in Antwerp, announced a partnership with Google Books aimed at digitizing more than 100,000 historic works over the next three years. For Google, this is just the third initiative of its kind in the Low Countries (following work at Ghent University Library and the Royal Library of the Netherlands), and it could significantly influence future research into the history and literature of the region.

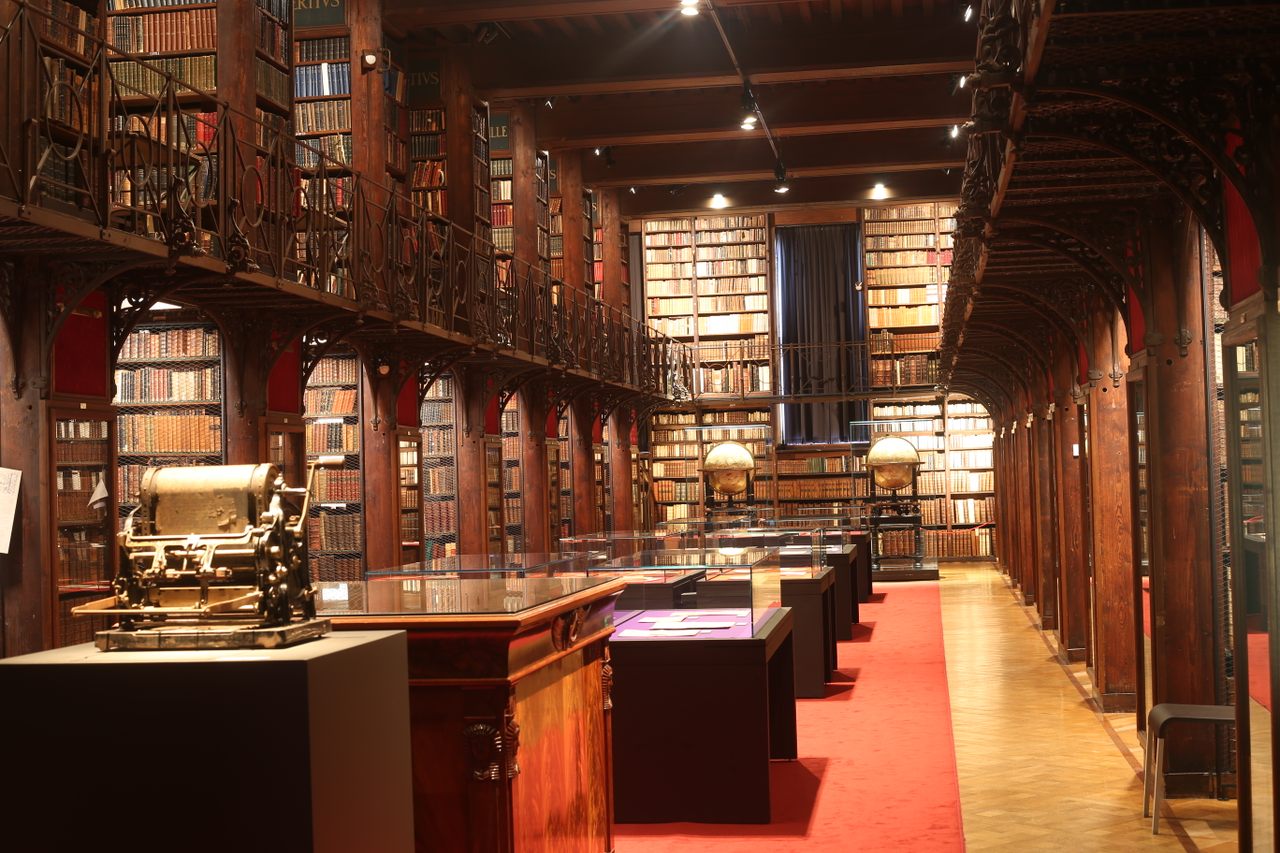

These works have traveled a long and rather perilous road to the web. The Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library, which now houses more than 1.5 million volumes and occupies a large, stately “Sodality” (or former Jesuit fraternity house), was founded in 1481, when a local official donated 41 books to the city. The budding collection, however, was not long for the Town Hall, where it was originally housed: The building burned down in the 1576 Sack of Antwerp—leaving probably just three surviving books, according to Steven Vam Impe, the library’s Curator of Early Printed Books and Manuscripts. It took several centuries—and several more moves—for the library to rebuild and grow its collection before it settled into the Sodality in 1883. But the inventory kept growing, so much so that the old building had to be expanded twice, including as recently as 1997.

Today the collection spans more than 20 miles of bookshelves, so one can imagine why researchers might relish the opportunity to more simply search for that they need. It’s a major victory for anyone interested in “Antverpiensia,” the Belgian city’s equivalent of Americana. According to the library’s website, “[t]here is an almost complete set of ordinances and city edicts from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century,” a set that’s still growing, as the city continues to stash all its official publications in the Heritage Library. The collection is also a repository for the records of local institutions from the Bar Association, to the Cathedral of Our Lady, to the Zoo.

Equally valuable is the collection of the Plantin-Moretus Museum, a UNESCO world heritage site. The museum is named for Christophe Plantin, the printer-publisher who lived and worked there in the 16th century, and his son-in-law Jan Moretus, who inherited the operation from him. According to UNESCO, Plantin-Moretus “is the only surviving printing workshop and publishing house in the world dating back to the Renaissance and Baroque periods,” and it “was the most prolific printing and publishing house in Europe in the late 16th century.”

The printing house spawned an astonishing array of influential publications: from the first Dutch dictionary, to a treatise on decimals that later helped create the American dollar, to an illustrated botanical guide that, in the 16th century, was second only to the Bible in number of translations. It even printed—be still, our hearts—the very first atlas, by Abraham Ortelius. (They won’t be digitized, of course, but it bears mentioning that the Museum is also home to the world’s two oldest printing presses.)

Because books will have to be transferred out of and then back into Antwerp by the thousands, the institutions estimate that it will take three years to digitize the 100,000 selected works, and more works will be added to the queue each year as their copyrights expire. Some, of course, are too fragile to travel, so they will be scanned on-site at the library or museum. Liesbet Wante, the project manager, says she cannot disclose the location of Google’s digitization facility.

COVID-19 quarantines will hopefully be over long before the entire collection is up and running, when it will serve as a source of Wonder from Home. Until then, the project is a timely reminder of all the stories still awaiting discovery, and all the uncharted territory that still exists—even in the digital world.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook