Journey Into the World’s First Underwater Farm

A team of Italian divers is growing basil, tomatoes, and strawberries.

Five years ago, Sergio Gamberini, a professional scuba diver and amateur gardener from Liguria, a coastal region in north-west Italy, was hanging out with local farmers. “I started wondering if crops could grow in the ocean,” he says. “I had this vision about a vegetable garden inside a transparent balloon filled with air.”

His friends were skeptical. But Gamberini, a chemical engineer who runs a scuba diving equipment business, was determined to prove that his idea could work. Two days later, he put on his diving gear and, 22-feet below sea level, attached a plastic balloon filled with a little pot of soil and basil seeds to the seabed. After a few days, tiny basil leaves were sprouting.

The following year, Gamberini, a self-declared “explorer of all things ocean,” devoted part of the budget of his family-owned business, Ocean Reef, to fund the first fully functional underwater farm. It was a matter of personal curiosity: “I want to find out if underwater farming can become a suitable alternative during my lifetime,” he says. He also hopes that if underwater farming takes off, he’ll be the one holding the patented technology.

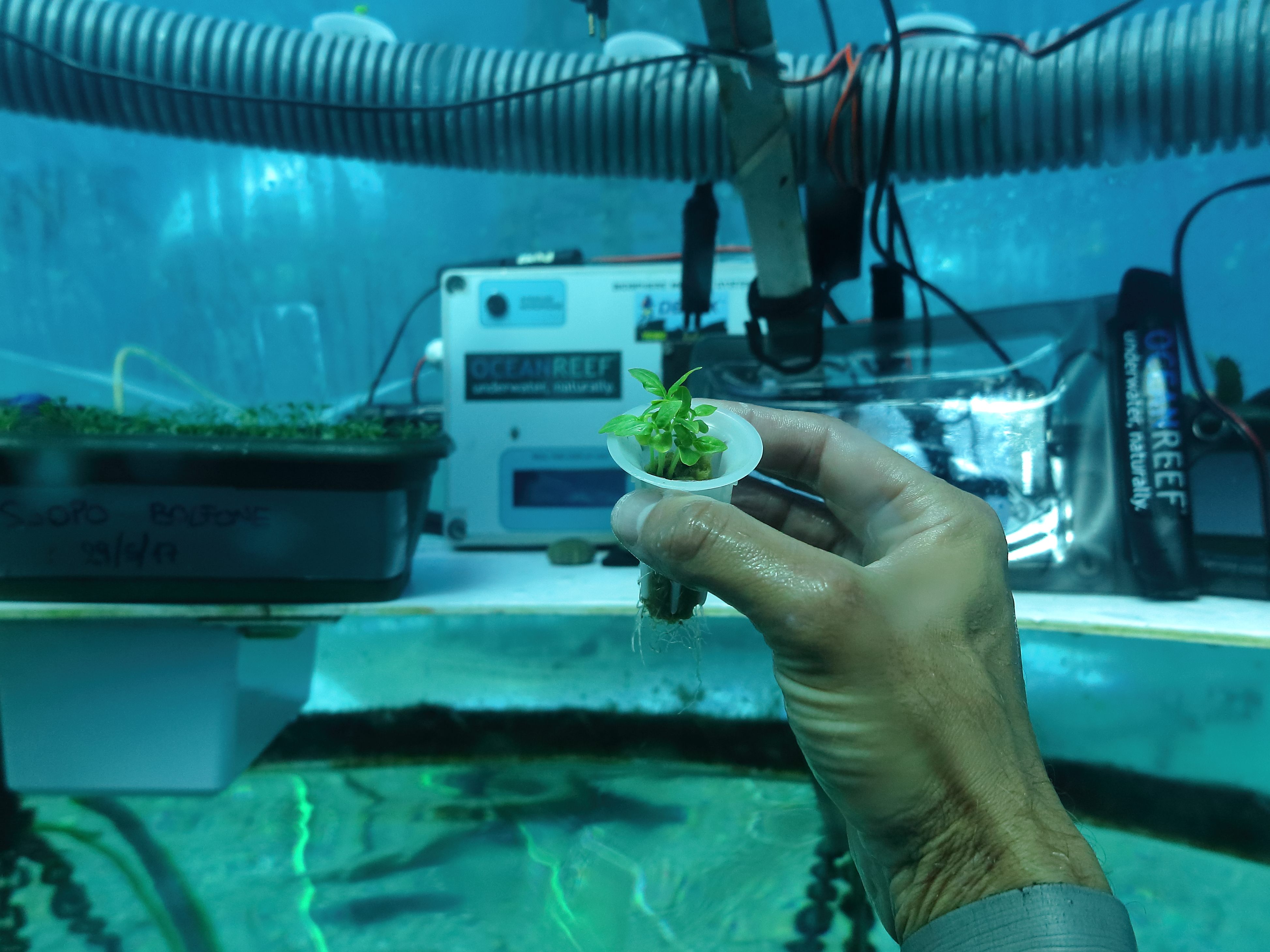

Today, his project, named “Nemo’s Garden,” counts six underwater greenhouses hosting an estimated 700 plants including basil, tomatoes, salad, strawberries, aloe vera, mint, marjoram, and liquorice.

The journey from what many saw as an “odd experiment” to full-scale underwater farm wasn’t easy. According to Italian environmental laws, it is illegal to make any permanent changes to the seafloor. So the first challenge was to create removable underwater greenhouses.

“At first we designed semi-spheres made of Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), a common thermoplastic material, that was very light and could be easily removed,” says Nemo’s Garden Project Manager Gianni Fontanesi. But after the first winter storm, when waves between nine and thirteen feet uprooted two of the underwater structures, the team opted for a different strategy. “We now use rigid plexiglass with an internal and external steel skelton,” Fontanesi explains, adding that finding the right design to prevent storm damage has been the greatest challenge to date. The semi-spheres are six feet wide and three feet high, and are attached to the seafloor with 28 (removable) screws. According to Fontanesi, this design ensures stability while allowing enough oscillation to prevent wreckage when waves hit.

Next, the team had to figure out the science of underwater farming. Most light is provided by natural sunlight. “We get 70% of sunlight compared with surface levels,” Fontanesi explains. During winter months or cloudy days, artificial light from LED lamps placed inside the spheres supplements the natural light. This electricity comes from solar panels and a small wind turbine onshore, which is fed to the greenhouses, along with water for irrigation, via a system of tubes shaped like a double helix.

For now, the project requires fresh water from land. But as Gamberini explains, the long-term goal of Nemo’s is to harness the natural desalination process that takes place in the greenhouses.

This would take advantage of the fact that the greenhouses are not entirely sealed. The bottom has a breach—used by divers to access the plants—that lets ocean water in. This does not mean that the entire biosphere is flooded. Much like in a bottle submerged underwater, water fills only part of the structures. Air pressure keeps it at bay, leaving the upper part dry.

When sea water comes in contact with the greenhouse’s warm air, it evaporates, losing its salty component. This “naturally desalinated” water eventually condenses on the greenhouse walls into droplets that can be collected and—after adding minerals—used for irrigation.

Gamberini and Fontanesi can monitor the temperature, air composition, and energy use from the project headquarters in Genoa, Liguria’s main city. But farming is done by visiting the greenhouses in person. To date, Fontanesi has logged nearly a thousand “farming dives.” He says it feels like being in an aquarium turned inside out. “You are the fish looking out into the outside world.”

Some environmental activists have raised concerns about Nemo’s Garden disrupting the surrounding ocean ecosystem. But Fontanesi says that, for now, there is no evidence of negative impact. “A few months ago, one of our divers found a large squid laying a nest beside one of the energy pipes,” he says. “So it seems that fish and other animals are finding a way to co-exist with our farm.”

In order to promote the project, the team allows any certified diver to come and check the site. “Many local people were initially skeptical about my bizarre idea,” Gamberini says. “But now people are realizing that it works, and it helps put Noli on the tourist map.”

September is probably the best time to visit. That’s when Nemo’s “harvest feast” takes place. “We get together with family and friends and celebrate the end of summer with food cooked with underwater plants,” Fontanesi explains. One of the gastronomic highlights is pesto, Liguria’s iconic pasta sauce, which is prepared with underwater basil. “Many people ask us if we can tell the difference from regular pesto,” Fontanesi says. “I am not a basil expert, but to me it tastes exactly the same.”

So far, the most surprising discovery regards underwater plant chemistry. Plants grown 22-feet below sea level face double the amount of atmospheric pressure compared with their counterparts on land. This, according to Fontanesi, has led to a different distribution of chemical elements.

Basil plants grown underwater, for example, have higher concentrations of eugenol (a substance contained in basil essential oils) and more chlorophyll (the substance that allows for photosynthesis to take place) compared with plants grown on land.

“For plants that have a medicinal or cosmetic use, this could translate into heightened therapeutic effects,” Fontanesi explains. He says that a French pharmaceutical company rented one of the greenhouses last year (he won’t disclose which one) and turned it into a lab to prototype products made with underwater herbs.

But the ultimate goal of the project remains to turn underwater farming into a viable option, especially in areas where water scarcity is an issue. “Eventually we want to create a system that is cost-efficient and energy-sufficient to offer a sustainable alternative to land farming,” Fontanesi explains. That will take years, at a minimum. But if he succeeds, a wetsuit and scuba tank could become as standard for farmers as overalls and tractors.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook