How a Dead Philosopher Makes a Transatlantic Trip

Jeremy Bentham died 186 years ago. Now conservators are transporting his “auto-icon” from London to New York for the first time.

Like all the other passengers on a commercial flight from London to New York next Monday, Jeremy Bentham will be strapped in. But the moral philosopher will have markedly less legroom than his fellow travelers. He’ll while away the 3,459 miles in the cargo hold, tipped on his back, padded with foam, legs bent in a sitting position. He’s bringing a bit of luggage, too. His wax head, chair, walking stick, and hat will be packed separately nearby.

A few days before the journey, Emilia Kingham—Bentham’s transatlantic chaperone—is quick to point out that the word “he” isn’t quite right. That’s because Bentham is more of an assemblage than a person.

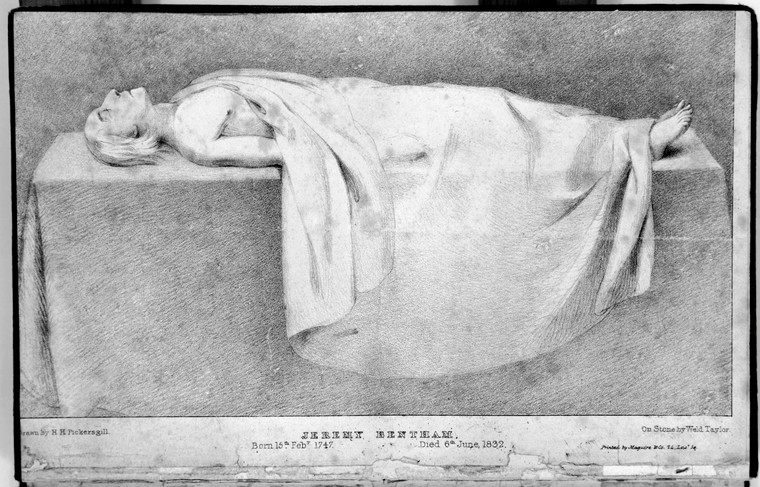

Before he died in 1832 at the age of 84, Bentham pledged his body to science and tasked his physician and friend, Thomas Southwood Smith, with preserving his corpse in a curious manner. On a paper affixed to his will, Bentham described his desire to be dissected in the name of anatomical knowledge, and then, “when all the soft parts have been disposed of, the bones are to be formed into a skeleton.” He then wanted to be outfitted in his clothes and “seated in a Chair usually occupied by me when living in the attitude in which I am sitting when engaged in thought.” In this way, he would be a perpetually curious intellectual.

Bentham’s “auto-icon,” as it is known, looks a bit like a figure in a wax museum, but there’s still a bit of Bentham inside. Beneath the clothes and a bodystocking are layers of linen tow stuffing—and then his bones, wired together. A wax head sits on top (more on his real, mummified head, in a moment).

The auto-icon is a hybrid sculpture and relic. University College London (UCL) acquired it in 1850, and today it usually sits in a secular shrine in the South Cloisters building, ready to receive visitors. It’s an oddity, to be sure, but the curators don’t consider it particularly lurid. It’s more of a provocation for discussions of life and death. For a while, the university produced a cheekily maudlin project nodding to the philosopher’s notion of the panopticon, a prison built around the idea of surveillance, by mounting a camera behind the auto-icon’s unblinking head to capture photographs of viewers.

The auto-icon’s trek to New York is by the invitation of the Met Breuer, where it will be included in the exhibition Like Life: Sculpture, Color and the Body. From March through July, Bentham’s remains will share a room with works by El Greco, Auguste Rodin, Louise Bourgeois, and more.

But before Bentham could board the plane for his first visit to America, the auto-icon needed some freshening up. “It can’t go on display all grubby and dirty and shoddy-looking, you know?” Kingham says.

The three-week process of preparing for the trip gave Kingham a chance to inventory its condition. Under regular circumstances, the UCL team tries to keep handling of the auto-icon to a minimum, because movement can be stressful for any old, fragile object. The conservators had “little tidbits of information” from previous research, Kingham says, such as X-rays from about 15 years ago and notes scribbled by Violette Lafleur, a conservator who treated the object in the 1930s. (Lafleur noted that she had encountered traces of a raging moth infestation, and swapped Bentham’s waistcoat for a garment donated by one of her friends.) “We saw this as a really good opportunity to investigate what [the auto-icon] is made out of, and what all the different components and elements are,” Kingham says.

There were reports that the feet were bundled in two sets of stockings, for instance, but little information and no pictures. (Now Kingham and company have proof.) If the conservators hadn’t had occasion to lift Bentham from his perch on the chair, they wouldn’t have noticed that moths had, at some point, nibbled the seat of his trousers to shreds.

The conservation process involved “spinning lots of plates at once,” Kingham says. How, for example, were they to ease the jacket off to check for pests, when they know that the wiring of the shoulder joint is broken? “We knew [the object] was already damaged,” Kingham adds, “and we were trying to minimize other damage from occurring.”

The auto-icon has also gone a bit lumpy in its advanced age. “When you have an old sofa, everything settles into the bottom and you have to plump up the cushions,” said Subhadra Das, a UCL curator, in a statement. “Well the same thing happened with Bentham.” The team smoothed out the stuffing, and now everything is more evenly proportioned.

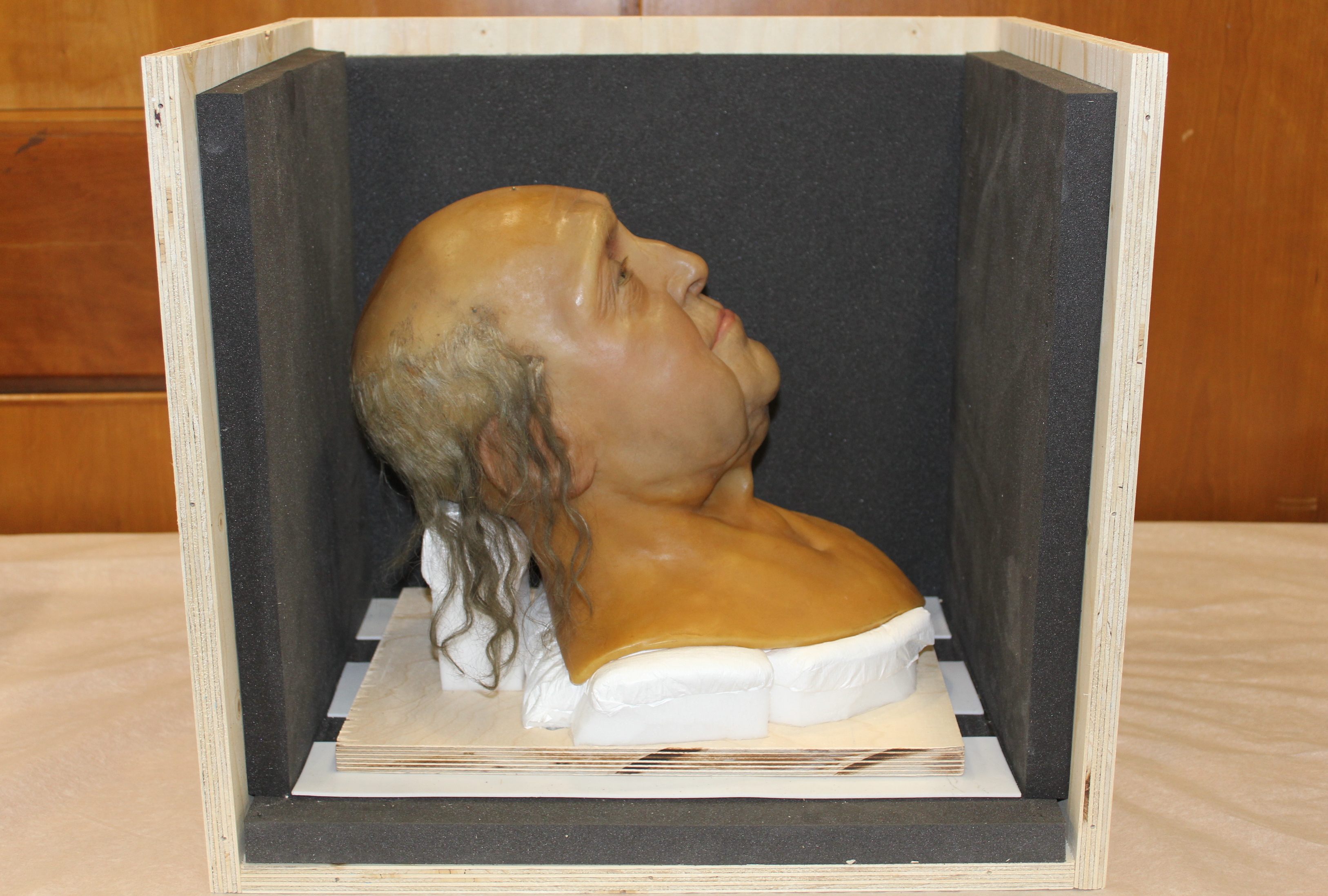

Other aspects have deteriorated far beyond any possibility of salvage. Bentham’s original scheme called for his real head to sit preserved atop his bones, but an experiment with sulfuric acid left the face shriveled and discolored. Anatomist Jacques Talrich was then enlisted to fashion a wax version of the head, while the mummified version sat between the object’s feet. (Over the years, both the original head and replacement noggin were pilfered—and eventually returned—by students from rival King’s College London.) These days, Kingham says, the reddish-orange, taut, and deeply grooved original is kept in a temperature- and humidity-controlled storage facility nearby, and won’t be making the trip across the pond. It’s in stable condition, she adds, “but it’s not particularly pleasant-looking.”

When the crates containing the auto-icon touch down in New York, Kingham will be anxious to get a look inside. She spent days making a padded mount for the fragile wax head. Even so, “it’s extremely nerve-wracking when you get to the museum site where you’re unpacking and you take the side of the crate off for the first time, and you see, ‘Oh my god, did everything make it in one piece?’” she says. The conservator is a little worried about that bum shoulder. If turbulence jostles the crate, she adds, “I know there’s a looseness there that could cause some slippage.”

“We were joking, at first,” Kingham adds, “wouldn’t it just be easier to wheel him onto the plane and book a seat for him?” For the long-deceased philosopher, it would have been an upgrade.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook