Remembering When Bermuda Was an Onion Island

Mark Twain once called the allium the “pride and joy of Bermuda.”

At just over 20 square miles, the island of Bermuda is barely a blip in the North Atlantic Ocean. Yet for much of the 1800s, this small British territory boasted an outsized reputation for one unlikely export: onions. In All About Bermuda Onions, Nancy Hutchings Valentine, a prominent Bermudian artist in her lifetime, writes that the island was growing 332,745 pounds of onions by 1844, mostly for foreign export. “Bermudian merchant seamen became known as ‘Onions’ and Bermuda was nicknamed ‘The Onion Patch,’” Valentine writes.

Bermuda onions, which flourished in the semi-tropical soil, became so famous that they attracted the attention of the literati. By 1877, when Mark Twain paid the island a visit, he was so struck by the alliums that he wrote, “The onion is the pride and joy of Bermuda. It is her jewel, her gem of gems. In her conversation, her pulpit, her literature, it is her most frequent and eloquent figure. In Bermudian metaphor it stands for perfection—perfection absolute.”

By the mid-1900s, though, this once-coveted crop vanished into near obscurity. It’s not that Bermuda onions ceased to exist. Locals on the island still grow plenty of alliums and are still sufficiently proud of them that the Carter House, a museum in a historic house dating back to 1640, holds an annual Onion Day Festival. St. Georges even hosts an annual “onion drop” in honor of New Year’s Eve. Instead, Bermuda’s onion preeminence was usurped by the muscle of the American agricultural industry.

Onions may not seem like the most glamorous of vegetables these days, but to seafarers in the 1800s, they were essential. Although they contain only modest amounts of vitamin C, they store better on long ocean voyages than most produce, making them a valuable tool in combating scurvy. Mild Bermuda onions were sweet enough to eat raw, saving the ship’s galleys the necessity of cooking them.

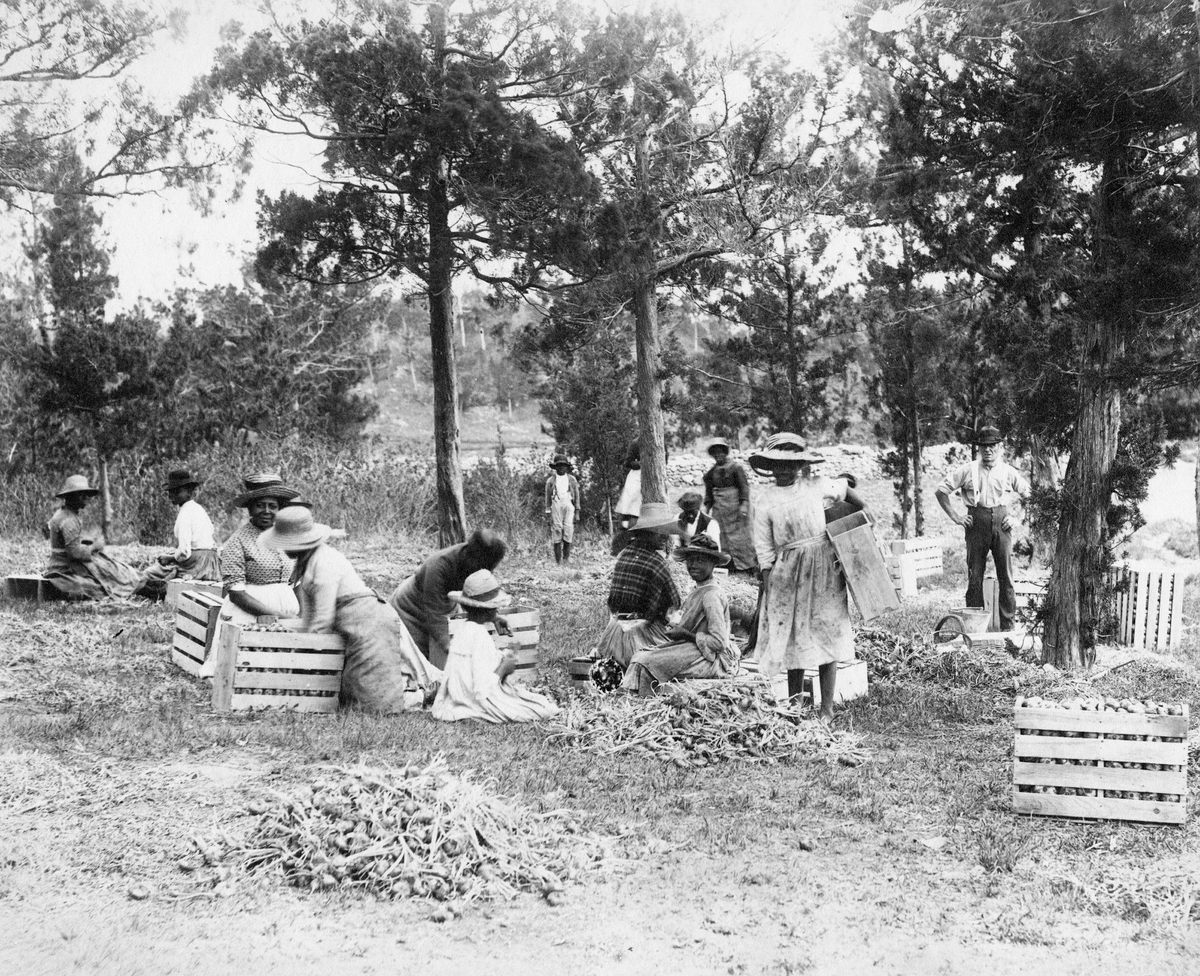

As with many crops in this colonized region of the world at the time, the history of onions in Bermuda is entwined with a legacy of forced labor and systemic oppression. Onions first took off as a crop in Bermuda when Governor Daniel Tucker brought them along in 1616 on a ship called the Edwin. Seeds were not this ship’s only cargo; the same voyage forcibly transported an enslaved African and a man identified as Indian (presumably from the West Indies) to the island.

Bermuda’s legacy of slavery and indentured servitude of Black and indigenous people would continue for generations, particularly within agriculture. Documented testimonies of Mary Prince and Mary Elsie Tucker, both of whom were born into Bermuda’s system of slavery, record being forced to cultivate onions, along with other crops. In 1979, Nellie Eileen Musson, a highly influential self-made Bermudian businesswoman and author, chronicled the legacy of Black Bermudians in Mind the Onion Seed: Black “Roots” Bermuda. The book was titled in honor of her grandmother, who was born into slavery in 1813 and worked in onions fields from childhood until Bermuda’s Emancipation Day on July 29, 1834. In it, she describes her grandmother’s duty at a young age to keep the “birds from eating the tiny, pearly-white onions seeds growing in the pods of the flowering onion plants” by swatting them away with a palmetto branch.

Agriculture had never been Bermuda’s primary focus, a fact that worried Governor Sir William Reid after he came into power in 1839. Fearing what might happen if Bermuda went to war with the United States and was unable to feed its population, he pushed Bermuda to develop its agricultural sector. In 1849, the first Portuguese immigrants arrived from the Azores and Madeira on a ship called the Golden Rule, in part to fill the labor shortage left by the end of slavery, as well as the rising demand for farming. These newcomers brought with them all sorts of new farming techniques and ingredients, including the seeds of what would become known as Bermuda onions.

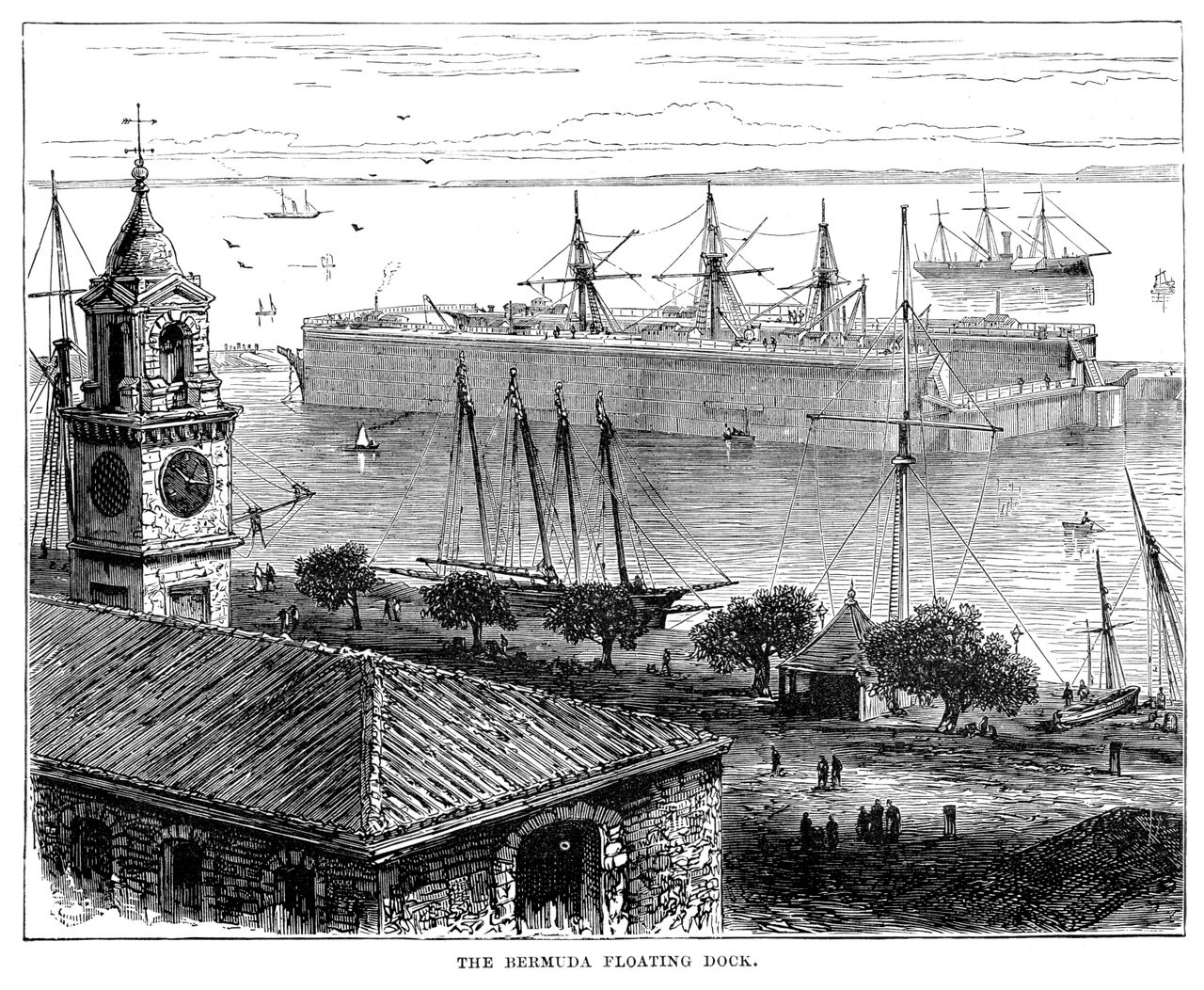

Within a few years, the Bermuda onion’s fame was well-established. When the Pearl, a ship sailed by Captain Solomon Hutchings, set sail for New York in 1854, some of its most prized cargo was 1,640 pounds of onions destined to be sold in exchange for fine silks and fashionable gowns for well-to-do Bermudian ladies. Towards the tail end of the century, the SS Trinidad was hauling 30,000 boxes of Bermuda onions to the United States every week.

In 1898, farmers in the south of Texas imported onion seeds from Bermuda in an attempt to corner some of the lucrative market. Despite a great deal of early speculation and excitement, the Texas onion market didn’t quite take off—until World War I. During the war, imports of the alliums ground to a halt. With the competition out of the way and food shortages plaguing Europe, some Texan onions farmers were reporting profits of $40,000 by 1917—a fortune at the time.

When trade resumed, the U.S. government slapped hefty tariffs on foreign produce to bolster its own agricultural industry. By 1920, the Texan onion industry was booming and Bermuda’s had been all but wiped out. One town in South Texas had the audacity to call itself the Bermuda Colony, or later simply Bermuda, as a marketing ploy to capitalize on the Bermuda onion’s brand.

As the decades wore on, hybrid sweet onions such as the Granex, a cross between a Bermuda onion and a Grano onion, and later the Vidalia, replaced Bermuda onions on grocery-store shelves. Nowadays, most sweet onions in the United States hail from Georgia, Texas, or Hawai’i. Meanwhile, in Bermuda, the alliums that once brought fame and fortune to so many are little more than a historical footnote.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook