Bile Beans, The Incognito Laxative That Claimed to Be A Cure-All

Thanks to unabashed false advertising, this 20th-century patent medicine survived lawsuits and eight decades of medical advancements.

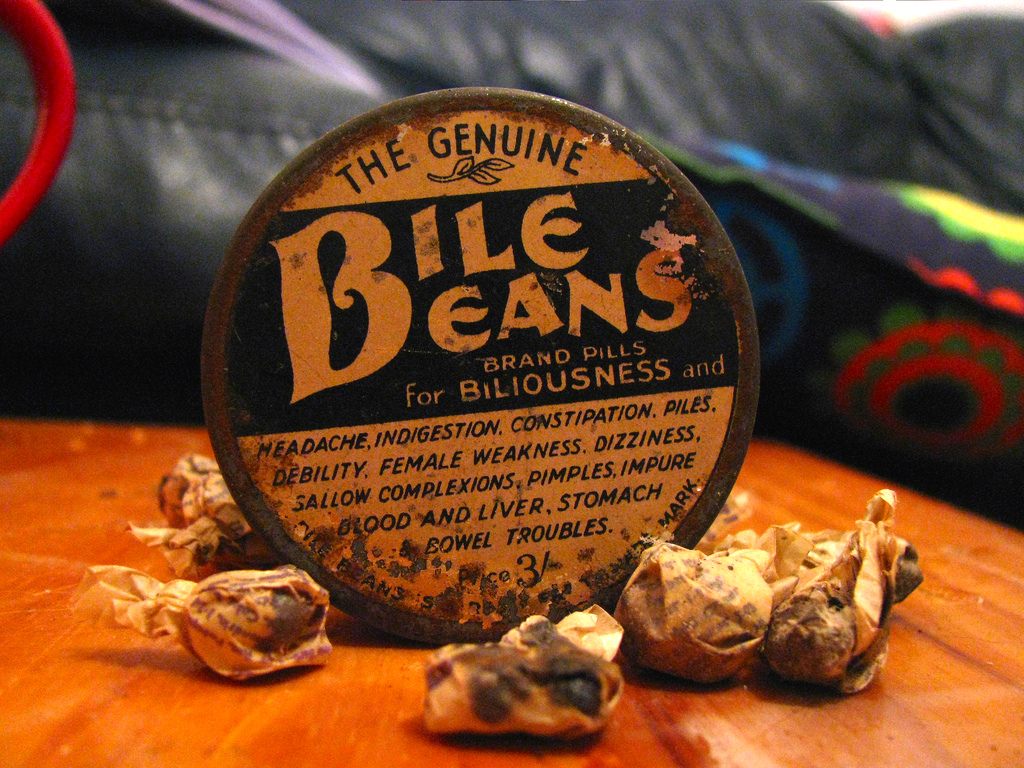

Bile beans, looking simply delicious. (Photo: essers/lightened from original/CC BY 2.0)

Headache? Stomachache? Blackheads? Cramps?

These days, such a panoply of ailments would require a variety of pills, if not a trip to the doctor. But if you were facing these symptoms in the early 1900s, you might just pop a couple of Bile Beans: black, gelatinous beans that—despite legal action, a foul smell, and general medical uselessness—captured the hearts, minds, wallets, and intestinal tracts of 20th-century hypochondriacs worldwide.

Even among the numerous “patent medicines” that distressed doctors and preyed on impressionable consumers throughout the Victorian era, Bile Beans were something special. According to the leaflets, medicine tins, and newspaper articles that told their story, they were the invention of Charles Forde, an Australian chemist who, based on a tip from noted explorer Captain Cook, had dedicated his life to studying the country’s roots and herbs. After finding the ones most suited to bile production, Forde had mixed them all together and “concentrated the product … until a suitable dose could be compressed into the space offered by a small bean.”

Bile beans among their contemporaries. (Photo: Chris Sampson/CC BY 2.0)

Great story; not quite true. “Charles Forde the Australian chemist” was Charles E. Fulford, a Canadian expat and aspiring entrepreneur. Fulford had traveled to Australia in the 1890s to hawk a similar product, “Dr. Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People,” for his uncle George Fulford. When those sold like wildfire, the younger Fulford began scheming toward his own piece of the patent medicine pie.

Thanks to his experience with the Pink Pills, and earlier years spent as a pharmaceutical shop assistant, Fulford knew which elixirs tended to fly off the shelves. Inspired by a few American successes, including “Dr. Morses’s Indian Root Pills,” he concocted the origin story for his new product. Somewhat less importantly, he also concocted the pill itself. As their name suggests, Bile Beans were originally meant to cure “biliousness”—an early term for indigestion, which was associated with both excess bile and grandiose living. Fulford settled on a mashup of, essentially, laxatives and flavoring agents: cascara, rhubarb, licorice, and menthol, rolled in charcoal powder and coated with shiny gelatin.

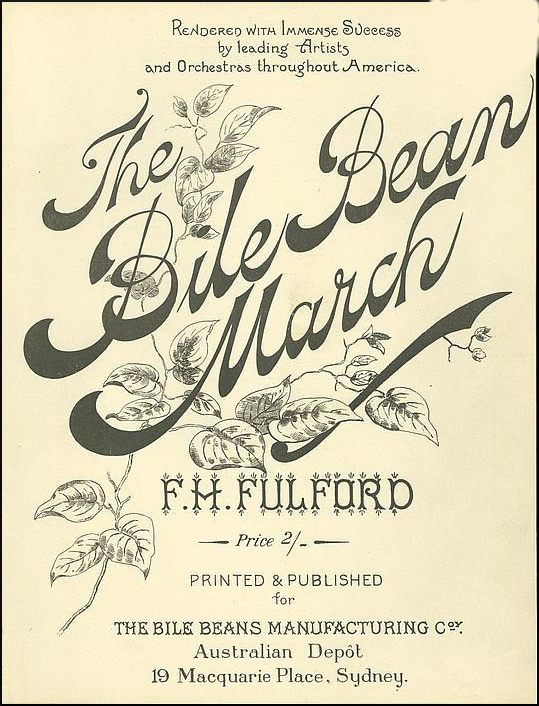

Frontispiece for the “Bile Bean March.” (Image: Bile Beans Manufacturing Company/Public Domain)

With that settled, it was time to take the product to market. Fulford had gotten himself a business partner, a printmaker named Ernest Gilbert, and together they began a multi-pronged advertising campaign inspiring in its ruthlessness.When they first moved into the U.K. market in 1899, they blitzed neighborhoods with millions of printed flyers, which they had “personally delivered to households by hordes of men.” They approached newspapers with what were essentially advertorials—testimonials “reporting” Bile Beans’ incredible curative properties, told by happy customers and cosigned by their awestruck neighbors.

Fulford and Gilbert also gave out Bile Beans-themed gifts: a “Cookery Book”; a puzzle book; sheet music for the “Bile Bean March” (composed by Charles’s older brother Frank, and complete with an endorsement from a mother who had been “preparing her daughter’s grave clothes” before said daughter was saved by the beans).

Amazingly, as these marketing plans diversified and expanded, so did the product’s purported abilities. When an influenza epidemic hit Britain in 1899, an article in The Northern Echo told the story of Mr. A.S. Selwyn, a flu sufferer who, after weeks of persistent symptoms, happened upon the beans and was cured “immediately.” “I ascribe my speedy and thorough cure to Bile Beans for Biliousness,” he told the outlet, which in turn instructed readers on how to order their own pills. “Please mention this paper if you are writing,” they added. Later versions of the packaging listed further bean-addressed ailments, including “headache,” “pimples,” and “female weakness.”

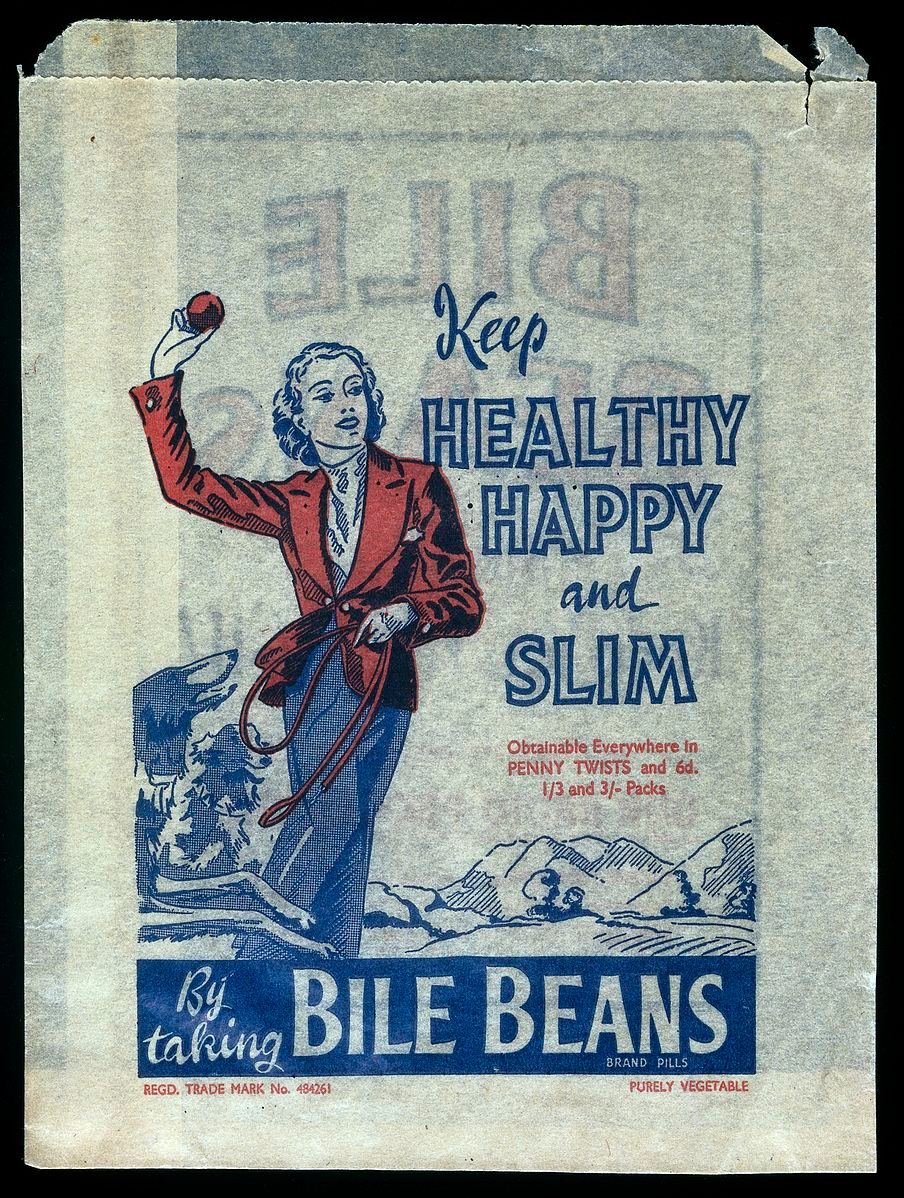

A 1930s paper bag shills for Bile Beans. (Photo: Wellcome Images/CC BY 4.0)

Bile Beans also quickly displayed an immunity to the legal system. In 1905, Fulford got a taste of his own medicine when, after suing an Edinburgh-based competitor for trying to snag the name “Bile Beans,” Scotland’s Court of Session found him guilty of far worse crimes. During the proceedings, the judge, Lord Ardwall, was appalled to find that Bile Beans’ origin story was false, that their product was contracted out to other chemists, and that inventor Charles Forde “was not a man of science at all,” but was in fact made up entirely. As the British Medical Journal reported at the time, Ardwall not only charged Bile Beans for the court time, but ruled “that they were entitled to no protection from the law, because their whole business was founded on, and conducted by fraud.”

This had no effect whatsoever on sales. Even Fulford’s early death in 1906 could not interrupt his leguminous legacy or killer marketing instincts. A bonafide bean magnate when he keeled over at 30, Charles left a portion of his sizable estate to his favorite charity, Dr. Barnardo’s Home for Friendless Boys. But there was one condition: the Home had to use the stock to open a satellite shop dedicated to selling Bile Beans. Barnardo’s eventually accepted a smaller, no-strings-attached lump sum instead.

A continually renewed sign for Bile Beans in York, England. (Photo: Ilovetigerplanes/CC BY-SA 3.0)

With Charles out of the picture, Frank took over, and things proceeded apace. He bought early radio ads, covered the U.K. with giant painted signs, and kept reinventing Bile Beans to fit the latest health trends. In 1940, as people became increasingly concerned with weight loss, a new campaign promised to “disperse unwanted fat” and “tone up the entire system.” Two Bile Beans, taken at bedtime, let you “slim while you sleep,” assured the ad, which also showed a smirking, pearl-strewn woman. Frank got rich enough to buy a castle, and died, even richer, in 1943.

Though they reached peak popularity in the ‘30s, Bile Beans remained on the market until the mid-1980s, when sales of general-purpose laxatives diminished. But now that they’re gone for good, their healing powers have, in at least one way, increased. In 2012, the city of York took a long look at their Bile Beans sign and found that it had faded and peeled, as we all do, with age. At the request of the local Civic Trust, the public happily donated $2,500 to give the ad a fresh coat. “It puts a smile on your face when you go past it,” said Civic Trust director Peter Brown. That’s the best medicine, after all.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook