How One of Brazil’s First Openly Gay Soccer Referees Changed the Game

The man known as Margarida refused to let prejudice affect his flashy officiating style.

Every four years, as the FIFA World Cup approaches, a video emerges from the dusty threads of soccer fandom and circulates across social media platforms. The 2014 video is a pixelated compilation of a soccer (or football, depending on where you live) referee officiating while gleefully running backwards and scissor kicking.

When he gives players yellow cards, he does not simply take them out of his pocket. That’s too boring for Clésio Moreira dos Santos. Rather, the Brazilian referee bends his back to a 45-degree angle, jolts his left arm into the air, and bestows the fouled player the card, as if it were a gift. Sometimes he high-knees to a corner, bows down, and points to the corner with his index finger, starkly indicating where the corner kick should be played.

While this may seem fun, Clésio wasn’t the first to trademark this spirited, jazzy officiating style. That title belongs to Jorge José Emiliano dos Santos, popularly nicknamed Margarida, who emerged as a figure in Brazilian refereeing during the 1980s. Jorge was an influence to Brazilian referees but his rise to prominence came with many challenges that reflected the time.

Growing up in Copacabana, Jorge never enjoyed the sea very much, but he loved the beaches. Not for relaxing or reading a book. He loved the beach because that’s where players met for quick pick-up soccer games. There, on the white sands of Copacabana, at age 13, Jorge learned how to officiate. He picked up the craft watching his idol on the field, Armando Marques, a well-respected referee who had officiated at high-level tournaments such as the 1966 World Cup. Marques was one of the early pioneers in Brazilian refereeing, and was known for his decisive officiating and making controversial calls. Debate wasn’t an option.

Over the years, Jorge started to referee bigger matches and tournaments outside the beach and in stadiums, such as the Rio de Janeiro league’s Guanabara Trophy in 1988. He garnered a fierce reputation as a no-nonsense referee in the machismo sport. “Expelling a player or calling out penalties is not for everyone,” said Jorge in a March 25, 1988 Placar interview with sports journalist Martha Esteves. He later said, “I do not allow any type of indiscipline and demand respect.” For that he was well respected among some players and other referees, but his officiating style and his sexuality garnered him the most attention.

The end of the military dictatorship in Brazil ushered in the early beginnings of LGBTQ civil rights activism in the late 1980s. Gay civil rights activist Luiz Mott founded one of Brazil’s first gay rights organizations, Grupo Gay da Bahia. This development helped pave the way for other LGBTQ advocacy groups. While there was greater awareness, at the time, being queer and open about it made one vulnerable to violence and discrimination, and still does. According to Grupo Gay da Bahia, roughly “3,100 homosexuals” were killed from hate-motivated crimes between 1980 and 2009, and the rate of violence against gay Brazilians is increasing.

Jorge, along with Válter Senra, who went by the nickname “the Bianca,” Paulino Rodrigues da Silva, and Sérgio Cenedezi, were the few openly gay Brazilian referees facing such scrutiny in 1980s. According to Placar, the president of the Brazilian Football Confederation (CBF) at the time, João Ellis Filho, stated that no homosexual referee would manage the Copa União competition. During a 1988 match between Volta Redonda and Flamengo, the crowd hurled slurs at him and criticized what they regarded as his effeminate physicality. These homophobic incidents happened quite often, but they didn’t phase Jorge.

“Good God! I’ve been hearing that for 20 years, why would I only now give it any weight?” He later added in the Placar interview, “I acknowledged my sexuality to a prejudiced country, which is a hard thing to do. Now if I happen to steal the show it’s because the game is boring.”

That fearlessness inspired many people in the Brazilian LGBTQ community, referees or not. Having seen Jorge on the field, some referees felt it was now safer for them to come out of the closet.

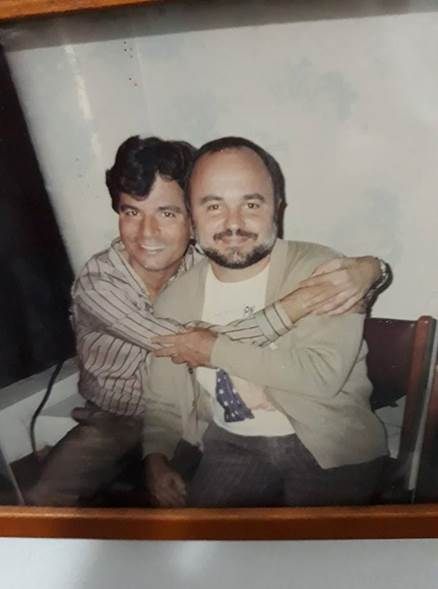

“When Margarida came on television to identify himself as a camp gay [man], we supported his visibility,” says Luiz Mott. He met Jorge for a few minutes in the late ‘80s during the recording of a show presented by Silvia Poppovic on the Canal Livre program. The show never aired, but Mott has fond memories of their encounter.

Despite the admiration, Jorge’s frankness and style often met swift retribution. Ironically, his muse, Armando Marques, committed during his tenure at CBF to ridding the organization of gay referees—or those, like Clésio, who were assumed to be gay. “I tend to say that I pioneered wearing such a feminine color,” Clésio says. (He wore pink on the field.) As the result of appearing more stereotypically feminine, “I was a victim of prejudices within the Brazilian refereeing boards.”

Still, this didn’t dampen Clésio’s enthusiasm to “get on the field and give my show.” Sergio Cenedezi received similar treatment. After being called the f-word, Cenedezi responded that he would rather be that than “a thief, like many of those who are today in charge of Brazilian football.”

Clésio left the CBF board in 2002. This independence gives him the freedom to officiate the way he wants to. The “gazelle step,” which is a seamless backpedal across the field, scissor kicking, and flashing of the arms before handing yellow card are Jorge moves, that Clésio has integrated into his officiating. He does not currently have goals to referee beyond officiating for small leagues.

“One day, I would still like to referee a World Cup final and leave the field to an ovation from the crowd. That would be glory for me,” said jorge when asked about his future ambitions. But that day never came. He died on January 23, 1995 from AIDS complications, a little less than a year after Brazil won the 1994 FIFA World Cup in Pasadena, California.

Almost 20 years later, it was big news in the soccer world when FIFA-ranked Brazilian referee Igor Benevenuto came out publicly as gay in the months before the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, where gay sex is illegal. Because of soccer’s reputation in Brazil as a “macho” sport, Beneveuto says, ““There was no more perfect place to hide my sexuality.” When he came out Benevenuto told the Athletic, “If I have to be a spokesperson in order to change things, I will be.”

For referees and assistants like Sérgio Cenedezi or gay soccer leagues like LiGay, that’s what Jorge represented in the 1980s. Images of him officiating are more than just funny videos. His gazelle style carries the hope that their beloved sport will one day accept them for who they are.

* This article was updated to include information about Igor Benevenuto.

This story originally ran in 2018; it has been updated for 2022.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook