Before America Got Uncle Sam, It Had to Endure Brother Jonathan

Brash, bold, and bigoted, he made for an uneasy national mascot.

He was ill-mannered and ill-spoken—a boor, a braggart, a ruffian, a bigot, a hick, and a trickster. His name was Brother Jonathan.

Today he is all but forgotten—eclipsed by his upstanding uncle, Sam. But after the Revolutionary War, Brother Jonathan was the personification of the newly independent American people: clever, courageous, not all that sophisticated and proud of it. He was the everyman incarnate. It was the everyman who had led America to victory. And now America looked to the everyman to lead them out from the bloated shadow of Great Britain.

During the nation’s first hundred years, America tried on many characters in search of the perfect fit for its new independent status. There was the feminine Columbia, the indigenous bald eagle, the stoic Lady Liberty, and the bumbling Yankee Doodle. Out of this personification soup, only a few emerged that had some staying power.

Many of these national stereotypes were depicted in popular ballads and stage comedies before America had even achieved its independence; Yankee Doodle was among them. He was originally a British invention—a caricature of a naive, upstart American colonist who was created as a foil for John Bull: the imposing personification of England. Though he never completely faded out of existence, after the Revolutionary War Yankee Doodle was mostly assimilated into another stage character: Brother Jonathan.

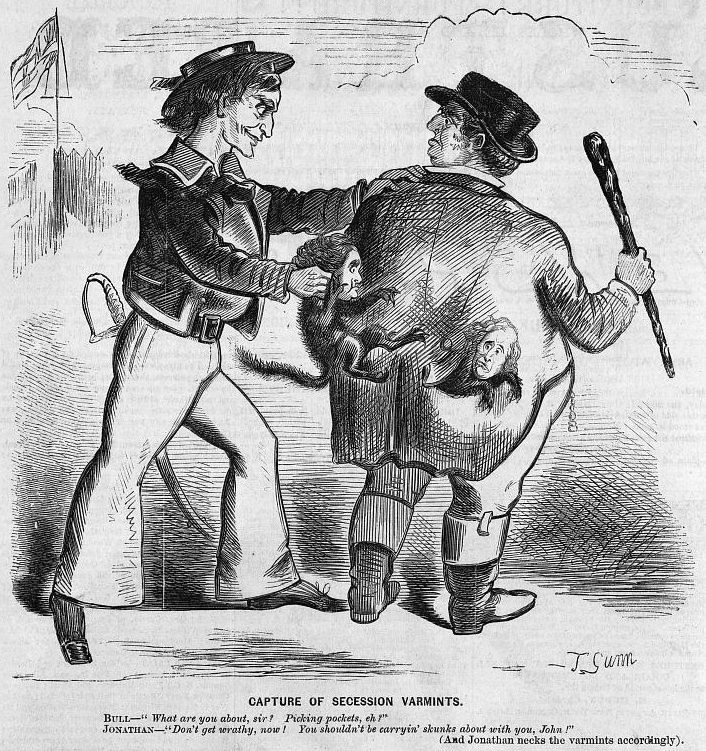

Brother Jonathan was a rustic New Englander who was depicted at various times on stage as a peddler, a seaman, and a trader, but always as a sly and cunning figure. He began to show up in political cartoons in newspapers and magazines during the early part of the 19th century as new and cheaper printing methods developed. It was at this point that American cartoonists transformed Brother Jonathan from a figure of derision into one of patriotic pride.

So who exactly was Brother Jonathan? For decades, his origin story centered around Jonathan Trumbull, the governor of Connecticut from 1769-1784 who was the only colonial governor to side with the patriots during the Revolutionary War. Stories were promulgated that George Washington had nicknamed the governor Brother Jonathan. But history has left us with no such account. The more likely source takes us to England were Jonathan was first used as a derogatory term for puritans and others who opposed the crown, dating back to at least the English Civil War in 1642. But Jonathan was also a common first name in New England, and the colonists who lived in the region during the 17th and 18th centuries were patriots. And so, the British may have glommed onto this familiar derisive term and called New Englanders, and all Northerners to some extent, Jonathans. Whatever the provenance, it is clear that Americans did not enjoy being called Jonathans—that is, up until the revolution. And then they took the name back.

American artists like Amos Doolittle shaped the character of Brother Jonathan into an inspirational hero for the new nation. In the cartoon “Battle of Lake Erie” from 1813, Doolittle depicts Brother Jonathan forcing John Bull to down an unfermented pear drink called perry, which was known to induce an upset stomach. Perry is also a pun. It was the name of the American naval hero, Oliver Hazard Perry, who defeated the British on Lake Erie in one of the decisive battles of the War of 1812. “Take it, Johnny—take it I say,” demands Jonathan as he pours the brew down John Bull’s throat. Brother Jonathan may have been obnoxious, but he got his point across.

While Yankee Doodle was primarily a comedic figure, Brother Jonathan was a more sinister one. Winifred Morgan, author of An American Icon: Brother Jonathan and American Identity sees Brother Jonathan during this period as a trickster in the tradition of Native-American and African-American folklore. “Tricksters are phenomenally powerful characters,” says Morgan. “They’re tough, they’re resilient, and Brother Jonathan has those qualities. But tricksters are also sly and self-interested.” And Brother Jonathan had to be. After all, he represented ordinary Americans who were trying to make their way in the harsh new world.

Americans liked to think that their wit and tenacity had won them their independence. They continued to see themselves as scrappy underdogs and turned their noses up at any whiff of pretension. This attitude played out in the political cartoons of the day which pitted Brother Jonathan against John Bull is a battle of old-world pomposity against new-world smarts.

The contrasts were striking. Brother Jonathan was tall, humorous, crude, cunning, plain-spoken, and simply dressed. In other words, the antithesis of the stout, stiff, aging, imperious, well-educated, and highly-cultured John Bull.

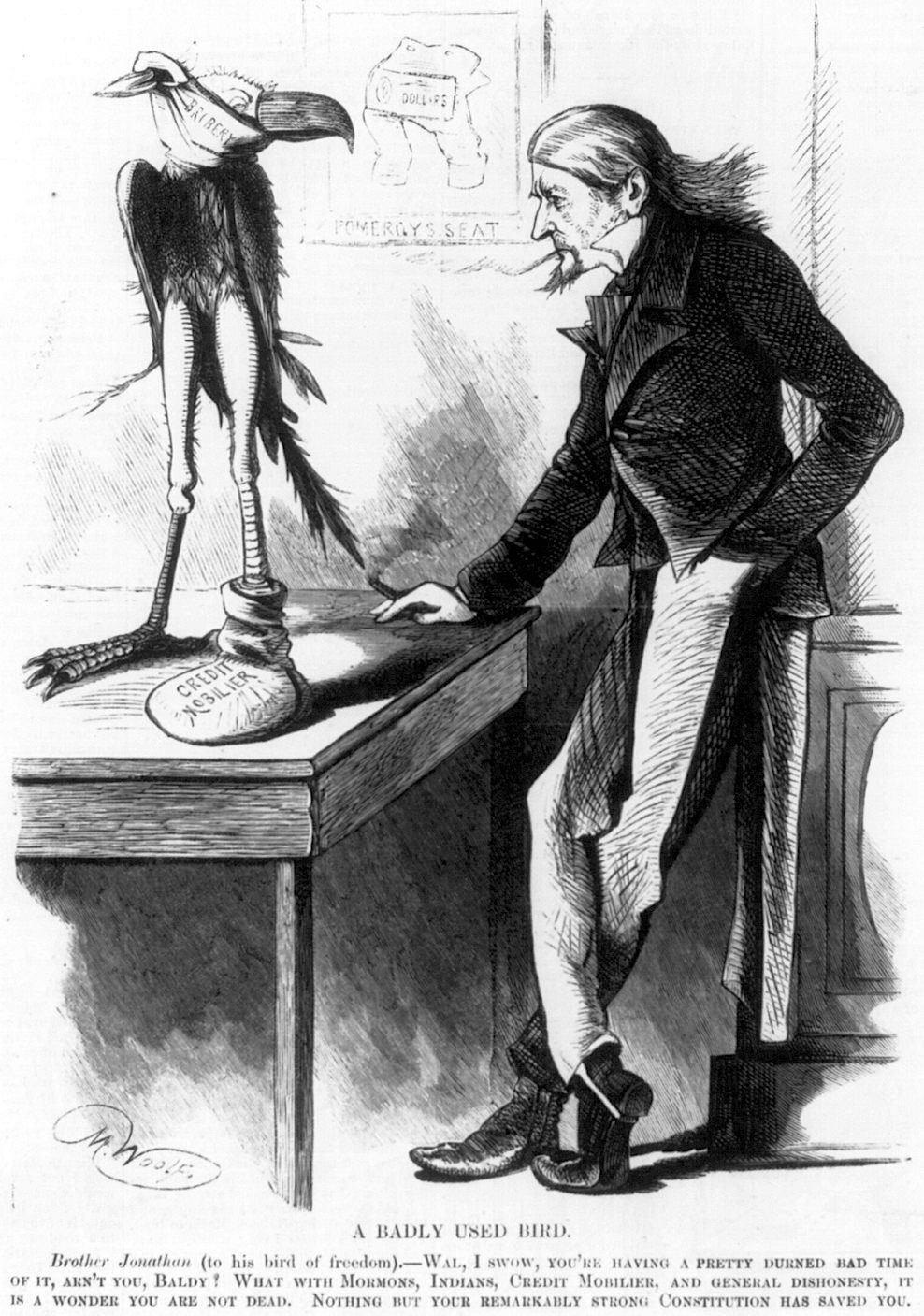

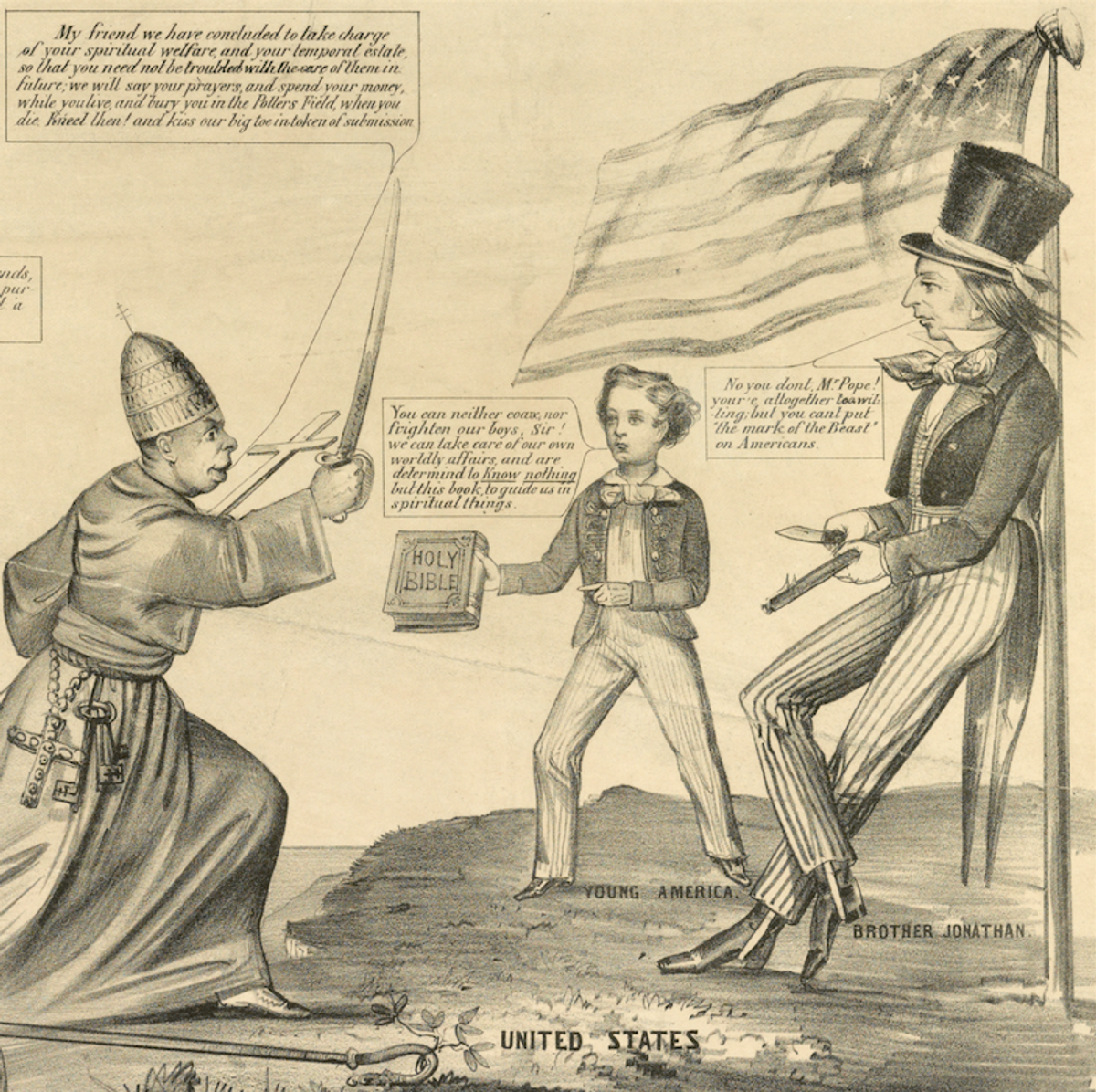

Over time, Brother Jonathan lost his barbed humor and gained more xenophobic traits as a mouthpiece for the nativist Know-Nothing party. In the cartoon “The Propagation Society. More free than welcome,” Jonathan embodies the party’s anti-Catholic platform as he protects “Young America” from an invading pope. And Jonathan’s intolerance was far-reaching. In “The reconstruction policy of Congress, as illustrated in California” he is depicted as opposing voting rights for African-Americans and other minorities, asserting “this ballot box was dedicated to the white race alone.”

As the century wore on, Brother Jonathan began to lose his panache and his relevance. Between the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, a current of romantic individualism ran through American culture and politics. Americans had considered themselves fiercely independent and rarely in need of the government’s services. Brother Jonathan reflected this attitude. It was always Jonathan (i.e. the people) versus the leaders (i.e. the elites and the government). But all that changed with the Civil War.

The power of the central government had increased considerably during the war. Individual lives were touched ever more by the government through legislation and projects such as conscription laws, the Homestead Act, and the transcontinental railroad. When the war was finally over, individualism was ceded to the more pressing business of reconstruction. As an anti-government figure, this development posed a problem for the sclerotic Brother Jonathan. Americans no longer needed a character to antagonize the government on their behalf. There was another problem, too. Brother Jonathan was a regional character—a Yankee from the North. No self-respecting Southerner or Westerner truly identified with him. He was not a figure who could personify a newly unified nation. That task had to be taken on by someone else.

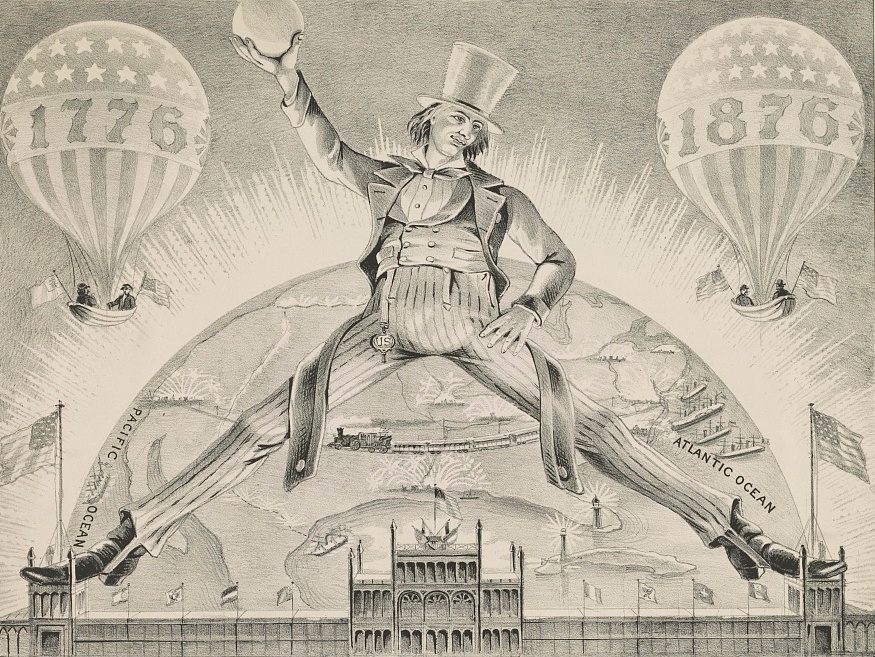

Uncle Sam had long existed alongside Brother Jonathan, but as a less prominent character. During the Civil War, American and British cartoonists started dressing Uncle Sam in the long-tailed blue coat and red-and-white striped trousers that had been worn by Brother Jonathan. At the same time, Uncle Sam started to acquire Lincoln-like aspects, including as a stovepipe hat and a sizable beard. Eventually, Brother Jonathan faded entirely into the figure of Uncle Sam who became the stoic, sober, adult version of the American government that was needed in the wake of the war.

There is only one known panel in which brother and uncle appear together. “Uncle Sam sick with la grippe,” likely published in 1837, depicts Uncle Sam slumped in an armchair suffering from financial woes while Brother Jonathan stands outside the sick room window beseeching a doctor to cure the ailing Sam.

In the end, Uncle Sam proved to be the more robust of the two. A hundred and fifty years later, Uncle Sam lives on in the cultural imagination, used in everything from wartime recruitment posters to tacky car commercials. Uncle Sam’s identification with President Lincoln probably contributed to his longevity. He also gets points for originality. While Brother Jonathan and Yankee Doodle developed out of British characters, Uncle Sam did not. He was made in America.

* This article was originally published in July 3, 2017.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook