America’s First Butter Sculptor Was an Artist and a Celebrity

Despite her success, Caroline Shawk Brooks never forgot her sweet, creamy roots.

In November of 1877, around 2,000 spectators gathered in an auditorium in Des Moines, Iowa, to watch a unique demonstration. Before them onstage a woman in her mid-30s perched on a stool, wearing a white smock, her hair pulled tightly back. She held several wooden paddles and a straw brush, and before her was an easel with a metal milk pan leaning on it, filled up completely with butter. Next to her was a full brass band.

The show began, and the musicians struck up a tune: “La Marseilles,” the national anthem of France. As the woman scraped and brushed with her paddle, the butter on the easel formed wide cheekbones and a distinct forelock: Napoleon! The band switched to a different, more American song, and the artist quickly reshaped that first face, giving it furrowed brows and a strong nose: George Washington!

Suddenly, a low note from the tuba rattled the easel, and as Washington’s shoulder began sliding off the easel, the artist caught it with practiced calm and stuck it back on the founding father’s body. The room erupted in applause.

Today, butter sculpting is the purview of state fairs and agricultural halls, its subject matter heavy on cows, pop stars, and heads of state cuddling pandas. But from the mid-19th century through the early 20th, Caroline Shawk Brooks, aka the “Butter Woman,” used it to bring herself widespread renown. By exploring the sculptural possibilities of dairy, Brooks took herself from an early life as a farmer’s wife into a career full of national exhibitions, cross-country tours, and European travel—all despite naysayers who wanted nothing more than to melt her down.

Brooks had been artistically inclined from childhood, and she had shown a knack for unorthodox materials. As a kid, she’d sculpted a bust of Dante out of mud from a nearby creek. But as the art historian Pamela H. Simpson details in a short biography of Brooks, she didn’t take up butter sculpture until economic necessity demanded it, in 1867—“the year the cotton crop failed” at her farm in Arkansas, as Brooks herself told an interviewer.

At the time, women farmers often took charge of making and selling butter while their husbands worked out in the fields, and some distinguished their wares by using pre-made molds to press patterns into them: flower, shapes, or their own brand names. Brooks decided to take this trend a step further, meticulously carving her butter into animals, shells, and faces rather than simply using a mold. It worked: “Her friends and customers greatly admired—and readily bought—them,” writes Simpson.

The lean times eventually ended, and Brooks put butter sculpture aside for several years. But the idea kept churning, and the next time she needed a marketing gimmick, she turned to it once more. In 1873, when the local church’s roof caved in, Brooks sculpted a butter portrait, which fetched enough at the church fair to fund the repairs. (“The people there called it—the Butterhead!” she later told the Akron Daily Democrat.)

This brought her to the attention of a Tennessee businessman, who commissioned a likeness of Mary, Queen of Scots for his Memphis office. (By this point, Brooks had perfected her preservation technique, which involved fitting each sculpture into a flat metal milk pan and setting it inside a larger pan, which she kept filled with ice.) People flocked to see it: “To Mrs. Caroline Brooks of Ark. belongs the credit of combining the poetic with the edible, and affording the household on its daily bread a work of art,” wrote the Chicago Tribune.

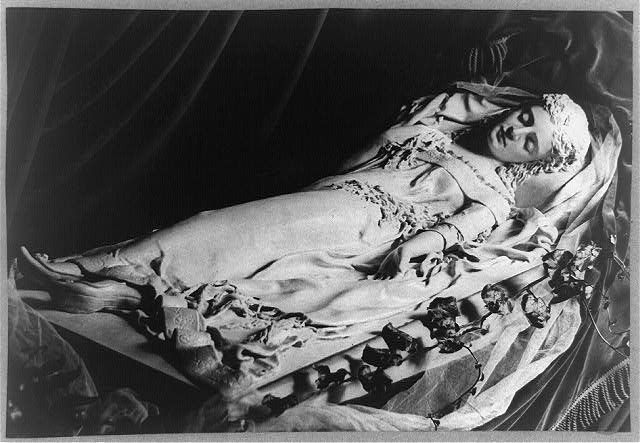

Later that year, Brooks came across the character that would become her lasting muse: Iolanthe, the innocent princess at the center of a popular play called King Rene’s Daughter. After losing her sight in a fire, Iolanthe spends her youth hidden away in a cottage, unaware of her blindness and plunged each night into an enchanted slumber by an attending physician. When she is 16, Iolanthe accidentally learns the truth about her condition, but after falling in love with a prince, she is finally cured.

The tale moved Brooks, and for the first time, she took up her butter-sculpting tools solely out of inspiration. “Brooks chose to depict that last moment of innocence before Iolanthe awakes to a new life,” writes Simpson. The result, Dreaming Iolanthe, pleased the artist enough that she brought it with her on a visit to Cincinnati. There, acquaintances of hers put it on display in a local art hall, where 2,000 visitors paid 25 cents each to see it. It even attracted the attention of The New York Times, which called it “a face that may yet make [Brooks] famous.”

Brooks kept creating new sculptures, which she displayed in several venues in Cincinnati. She was particularly attached to Iolanthe, though: even after she perfected a butter-based plaster-casting technique that could have allowed her to make infinite copies of the work, she chose instead to carve the sculpture anew each time it was needed.

One of these occasions was the 1876 Centennial Exposition, in Philadelphia. Lucy Webb Hayes, the future first lady and a big fan of Brooks, commissioned her to carve a Dreaming Iolanthe for the Women’s Pavilion. The sculpture was “beyond all comparison the most beautiful and unique exhibit in the Centennial,” raved J.S. Ingram in his popular event guide. It drew such large crowds that it eventually made its way to the more central Memorial Hall.

So popular was Brooks’s work that on October 14, she was asked to demonstrate her techniques live at the Judge’s Hall. Armed solely with two different-sized wooden paddles, reporters and judges watched as Brooks worked, first piling the butter into a granite basin bit by bit until she had a twelve-pound blob, and then placing it in a nearby refrigerator to harden.

She brought it out again and began carving away at it, placing it back into the fridge for brief stints in order to restore the desired texture. “In one hour and a quarter after she began work,” Ingram wrote, “the shapeless, golden mass was transformed into the relief bust of another sleeping beauty.”

Brooks “may have begun as a farmer’s wife trying to sell her dairy products,” writes Simpson. But by the time the Centennial ended, bolstered by this critical and popular reception, she began “aiming for something more.” After the Exposition ended, Brooks set off on an extended tour of the U.S., where she lectured art appreciators and demonstrated her techniques, sometimes with the aforementioned musical accompaniment. In 1878, she separated from her husband and opened a studio in Washington, D.C., where she began taking commissions from various upper-crusters eager to befriend the so-called “Butter Lady.”

This nickname notwithstanding, over the course of Brooks’s career, critics showed no qualms about encouraging her to switch over to what they viewed as a real material. “The talented lady should drop the butter paddle and take up the mallet and chisel,” one wrote in 1873. As her reputation spread, similar sentiments were raised by fans and skeptics alike.

East Coast critics poked fun at her, suggesting that if more public sculptures were made out of butter, issues of changing historical opinions might be resolved. When she entered a contest to sculpt a memorial for Ulysses S. Grant, the other entrants were “somewhat miffed” that the butter lady was allowed to compete among them, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported.

But although Brooks did eventually begin working with other materials, even spending seven years with marble-cutting artisans in Italy, she never forgot her roots. No matter the finished product—the state seal of Nebraska; a dual portrait of Grant and Chinese diplomat Li Hung Chang with a friendship knot over them—each work’s life began as butter, which she found to be better than clay at keeping its malleability, not to mention readily available. “I had previously modeled in everything workable, in clay, sea sand, mashed potatoes, putty and so on,” she told the Akron Daily Democrat in 1893. “[But] I began my best work in butter, and with butter I shall end.”

Brooks remained in D.C., sculpting, exhibiting, and hustling for commissions, until her death in 1913. “We know little of her final years,” Simpson says, except that she kept that promise. Tomorrow morning, as you spread butter on your toast, pour out a drop for a woman who took an everyday condiment to new heights, and herself along with it.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook