A Mysterious Cézanne Portrait Was Hiding Under the Layers of a Still Life

An X-ray offers a glimpse into the painter’s early years.

Last spring, the Cincinnati Art Museum held a special exhibition showcasing works by five young French artists, who, in the 1860s, used the still life genre to experiment with new painting techniques. One of those artists was famed Post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne, and the exhibition included Still Life With Bread and Eggs, one of his earliest masterpieces and part of the museum’s permanent collection. While the gallery was being rearranged, Serena Urry, the chief conservator, decided it would be a good idea to bring it down to the conservation lab for some cleaning. It wasn’t an unusual thing to do, but what she found was anything but routine.

Urry was unhappy with the way the varnish looked and wanted to remove some of it. She began the work with a thorough examination, where she noticed some cracks in really dark parts of the background. “I noticed that there was some white showing in the two areas of cracks,” she says. This often represents some type of layering problem. Because paints can dry (and contract) at different rates, it’s possible that layers of the oil paint were on different timelines. Urry hypothesized that a white layer may have been laid down before the dark one, hence the cracks.

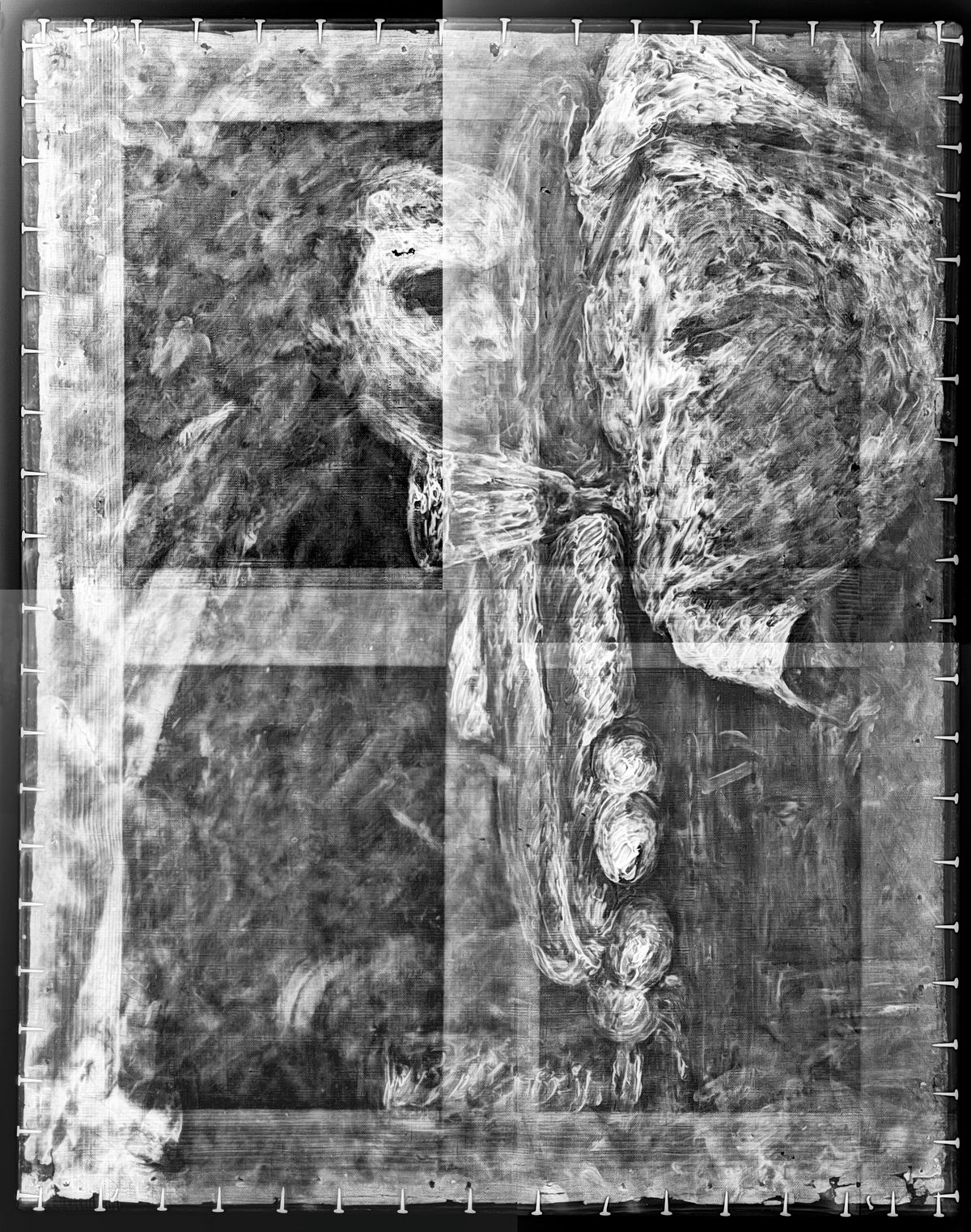

So she called in the technician to X-ray the painting. Still Life is big, so it had to be X-rayed in quadrants, with the images then stitched together on a computer. After composing the full X-ray, Surry printed out the final image. For no particular reason at all, she happened to get a look at it turned 90 degrees. Something special happened.

Rather than the X-ray signature of the white layer of paint she expected to see, Urry saw a ghostly face—a hidden painting, which the museum now believes could be a self-portrait of the artist, most likely from his 20s.

The X-ray, oriented on its side, has the original Still Life composition occupying two quadrants on the right. But the left side—the black backdrop of the final composition—reveals a face with deep set eyes and a distinct nose and mouth. The shape of the body is there, too, and upon close inspection, the white cuff of the subject’s right sleeve. It is probable that the alleged self-portrait was something Cézanne was working on at the onset of his career, in the early 1860s. He then may have put the canvas aside for a few years before re-using it for his earliest still life masterpiece, in 1865.

Still Life With Bread and Eggs was already an incredibly important piece for the museum, as it is one of a handful of works that Cézanne had signed and dated. According to Peter Jonathan Bell, Curator of European Paintings, Sculpture, and Drawings, the discovery of the hidden portrait offers a glimpse into Cézanne’s studio at the beginning of his career. Born in Aix-en-Provence, France, in 1839, Cézanne fled to Paris in 1861 to pursue his artistic dreams, against the wishes of his banker father. “What has gotten people in the art history world excited is that the portrait gives us the moment Cézanne is trying to break into the salon and start his career,” Bell says.

“I interpreted it as a self-portrait based on the way he’s posed,” says Urry. “He’s got his body sideways and that generally is a self-portrait position.” While some scholars share that opinion, according to Bell, others with experience with Cézanne’s works have different suggestions. “Cézanne did a very famous series of portraits of his uncle where you could see some physiognomic similarities there, too,” he says. “People are all over the map right now.”

Further detective work is needed, which begins by conducting more imaging and analysis. “Conservation science has really grown leaps and bounds in the past decade,” says Urry. The 19th and 20th centuries saw increased collaboration between the arts and science, but many American art collections had long relied on outside restorers to care for their paintings. That changed in the 1940s, when institutions began implementing a more systematic approach to care and preservation, and a more scientific approach to the treatment of artwork. Since the early 1990s, the number of conservation scientists and scientific research laboratories in the United States has increased. Today, conservation departments and centers have been integrated as part of museums across the United States. Not only has this global trend allowed museums to facilitate collaboration between art historians, conservators, and scientists, but it has led to a number of surprising discoveries, from a hidden landscape painting under Pablo Picasso’s 1902 masterpiece The Crouching Woman to abandoned sketches under Leonardo da Vinci’s 1483–86 altarpiece The Virgin of the Rocks.

One of the next steps to further analyze the newly discovered portrait would be an X-ray fluorescence scan to map where elements in pigments, such as iron, cadmium, and silicon, reside. This, Urry says, “would give us a sense of what the color was or what the mixture of colors were.”

Urry, however, is the sole paintings conservator at the museum; access to resources and analytical techniques is a challenge. “Still Life With Bread and Eggs has been around since 1865 and it isn’t going anywhere,” she says. “We’re going to do our best to get as much information as we can about the portrait and disseminate it to the art history world.”

Urry and Bell are optimistic that with continued advancement, someone will one day be able to image the entire painting without disturbing the still life. For now, Still Life With Bread and Eggs is back in public view, just as it has always been, but with a new neighbor: a high-resolution image of the X-ray.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook