Were Colonial Men Obsessed With Their Calves?

The difficulty of substantiating—and quashing—a historical rumor.

A couple of weeks ago, at an event in Manhattan, I found myself in conversation with a George Washington impersonator. Even as we chatted about our 21st-century lives, he had an enviable commitment to the aesthetics of his character—he stood straight as a tree, and the gravitas never left his face.

Posing with me and a friend for a photo, he instructed us to keep our left legs straight and turn the right ones outward. “In colonial times, the calf was the most attractive part of a man,” he said. “Some even put calf enhancers in their socks, to look beefier.” He struck the same position, effortlessly, and the camera flashed.

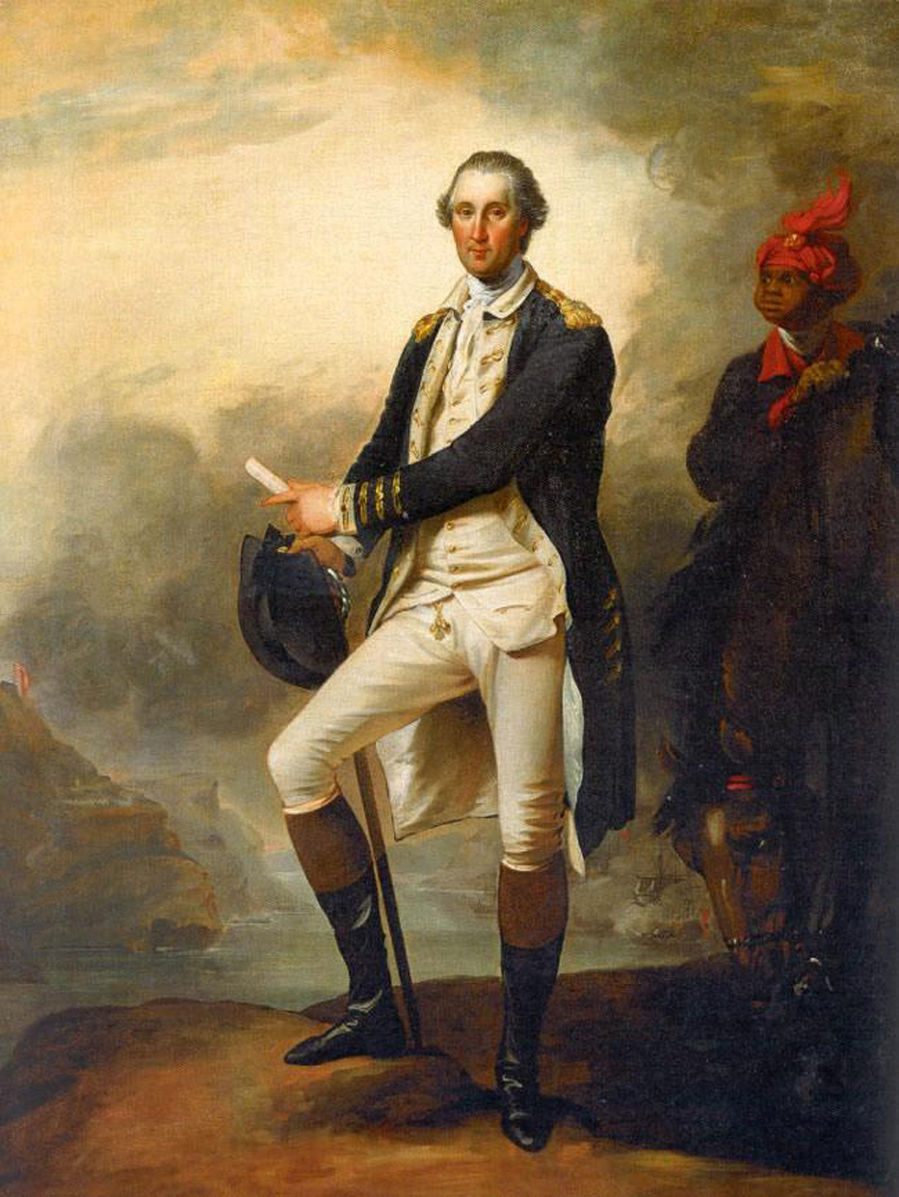

I found this bit of news delightful. Our Founding Fathers, signing the Declaration in calf falsies? Suddenly, everything made sense—the fact that breeches end at the knee, the phrase “put your best foot forward,” the many portraits of colonial luminaries thrusting their calves at the viewer.

Guide Sue is teaching Colonial Etiquette. The man’s calf was the most attractive part and woman’s hips. pic.twitter.com/ToSnApXNVv

— Team Genius (@Teamgeniusdc15) June 7, 2015

Online, history buffs seemed similarly tickled. After a trip to Colonial Williamsburg, one fan theorized about what he’d learned that day: “The exercises a successful male Colonist gets over his not-as-successful counterparts include activities like horseback riding (stirrups strengthen calf muscles), stairs (your home must be larger with upper floors), waltzing (try that with weak calves), etc.”

In fact, many young men on trips to historic sites have apparently learned how to enhance their calves by posing: “Daniel learned that to woo ladies in colonial times you had to have nice calves and put your best foot forward,” one teacher tweeted from Old Town Alexandria, with a photo of poor Daniel. Alexander Hamilton superfans love to repost this page from a children’s book about the Founding Fathers, which asserts that Hamilton, unlike some of his peers, had no need to stuff sandbags in his stockings. “If you’re bowing to a man, your calf projects your power,” famed George Washington impersonator Dean Malissa told Esquire in 2010. “If you’re bowing to a woman, your calf projects something else.”

In a world where the current U.S. president has spent his life defending the size of his hands, it’s both amusing and humbling to consider that giants of history might have had their own now-ridiculous sticking point. There’s just one problem: it’s probably not true. Or at least, not as true as people seem to want it to be.

When I got in touch with experts at Colonial Williamsburg about this, I was met with the rhetorical equivalent of a heavy sigh. “The notions that people in the 18th century were obsessed with men’s calves and that a well-developed calf was the sign of a gentleman appear to be myths,” writes Cathy Hellier, a historian at Colonial Williamsburg, in an email. Mark Hutter, supervisor of the Tailor Shop in the Department of Historic Trades and Skills, backs her up: “It’s not at all uncommon in historical interpretation for small grains of truth to grow into greater folklore,” he says. “I think this is an instance of that.”

Hellier, who studies deportment, has a few theories about how this idea got so much traction. First, there’s the phrase “to make a handsome leg,” a fairly common expression in the 18th century. In reality, though, this just means “to bow in a genteel way,” something that involved a lot of minute movements, including a leg turn. She also points out that, although dancing and horseback riding certainly work the calves, so do activities associated with the less well-off, such as plowing and walking.

This isn’t to say calves weren’t considered sexy. “There certainly is preference for a good leg,” says Hutter—and Washington, for example, is on record as having had exquisite ones. They just weren’t the be-all end-all of attractiveness, or even close. In fact, Hellier points out, when you trawl through the many, massive etiquette books of the time, you hardly see legs mentioned. “Letters, diaries, and books generally ignore or downplay the appearance of gentlemen’s legs—a singularly odd omission in an era supposedly obsessed with them,” she writes.

All those turned-out legs on portraits and statues, Hellier says, reflect their subjects’ substantial dance training, and the pose was actually meant to emphasize the hips, not the calves. According to The Young Gentleman and Lady’s Private Tutor, a 1770 etiquette guide, turning the foot outwards makes “the Hips… appear firm, yet light and easy.” If turned inwards instead, “they will appear heavy and misplaced, awkward and ungenteel.” When “standing genteel,” he suggests, “the whole Body should rest on the left Foot.”

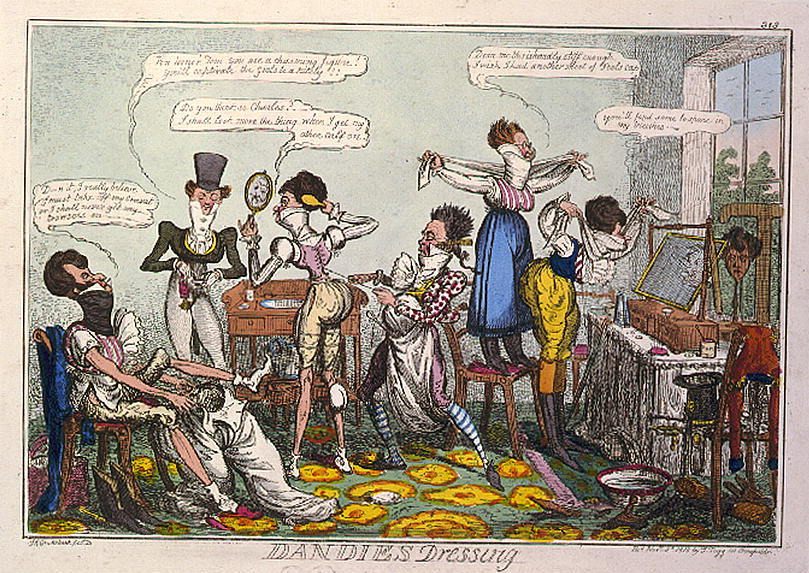

As for the falsies, those were actually real—but accounts of them appear to be pumped up as well. While my secondary-source research alluded to cork, parchment, pith, and sandbag calves, the only type that turns up in primary sources is the “downy calf,” essentially a padded stocking. Even these were likely pretty uncommon. When padded calves show up in literature, Hutter says, they’re almost always used to satirical ends, worn by dandies in cartoons or characters named Lord Foppington.

He also points out that even these cartoons don’t show up until the beginning of the 19th century—right when men’s deportment changed, and people began keeping their legs straight beneath them while bowing. “I would say that, if anything, this argues against the idea that you’re showing off a leg” when you bow, he says.

It’s tricky to quash a historical rumor—especially one that was likely started by well-meaning experts, and has been perpetuated by enthusiasts. “I do think that, through the public interpretation in places like Colonial Williamsburg, and then probably spreading to other historic sites, these ideas have sort of entered the popular mind,” says Hutter. But those who are invested in bringing the historical record to life also consider it their responsibility to correct it. “We are making an effort to root out these fallacies,” writes Hellier.

“It’s part of the nature of history,” says Hutter. “Grains of truth grow into great beaches of myth.” Or, in this instance, into great calves.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook