The Dazzlingly Colorful Atlases That Brought the Night Sky Within Reach

Detailed maps of the heavens weren’t just for scholars.

If you lived in London in 1822, you might have found solace in imagination. With skies dark with soot, rivers sludgy with sewage, and streets crowded with people, carts, and waste of all sorts, perhaps you looked to the heavens for some kind of escape.

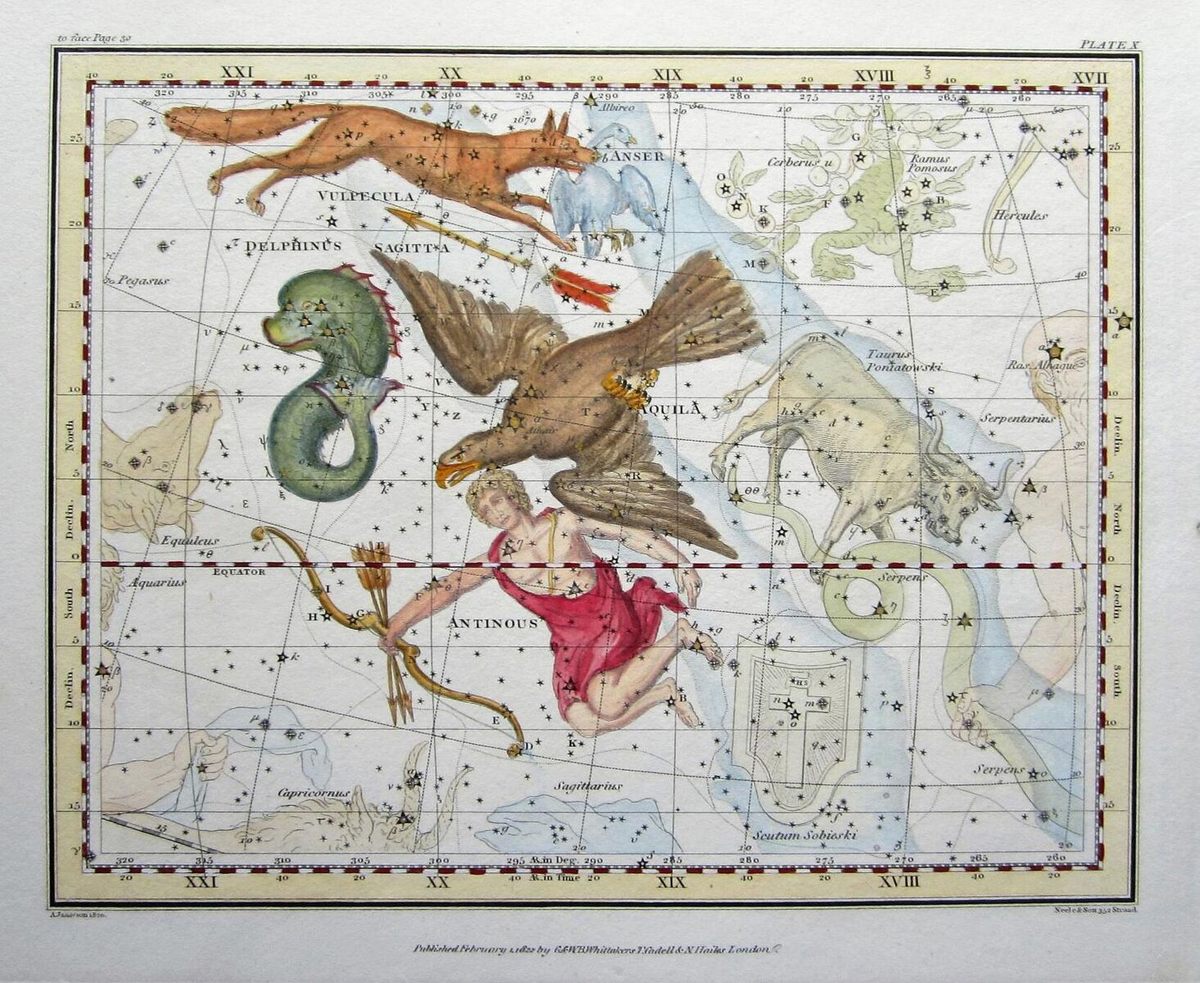

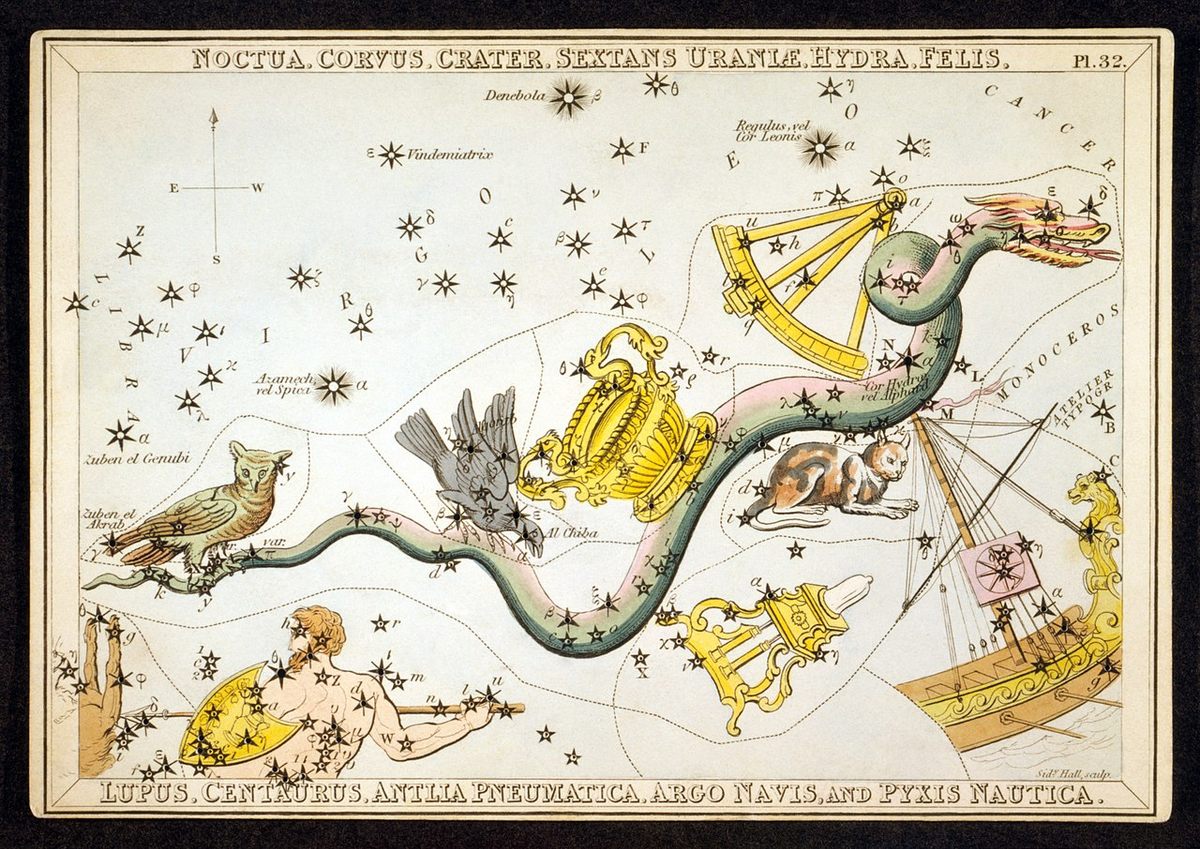

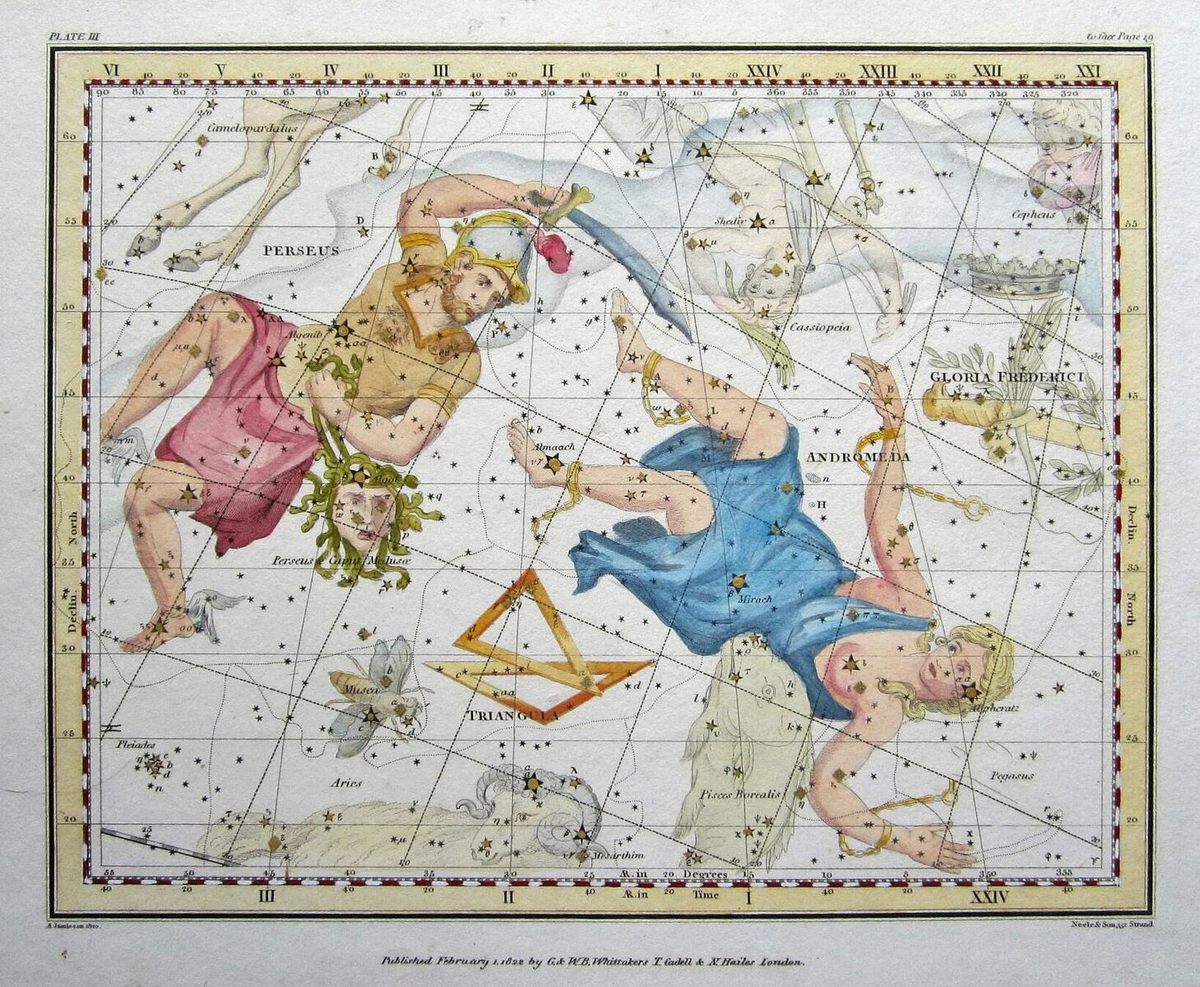

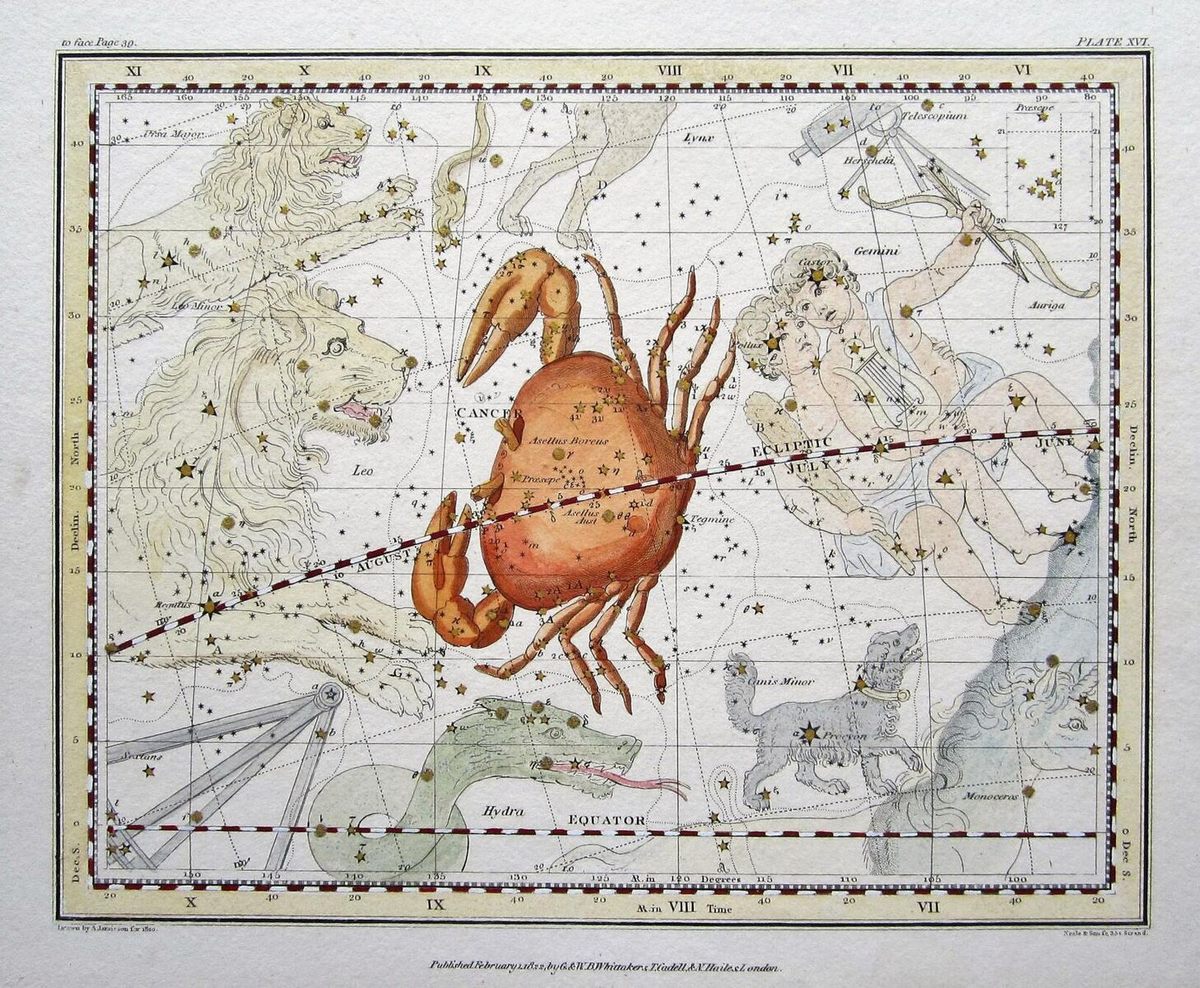

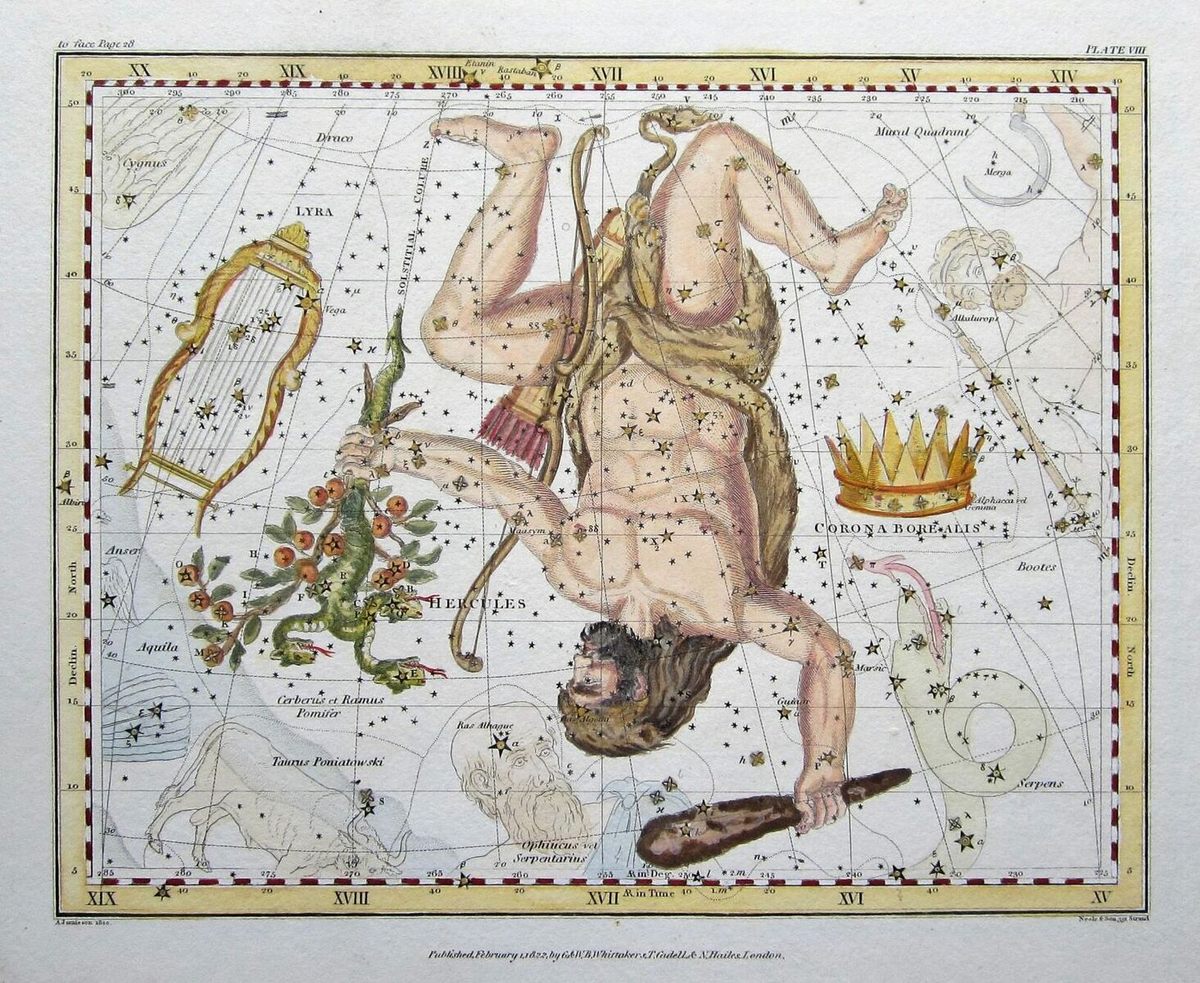

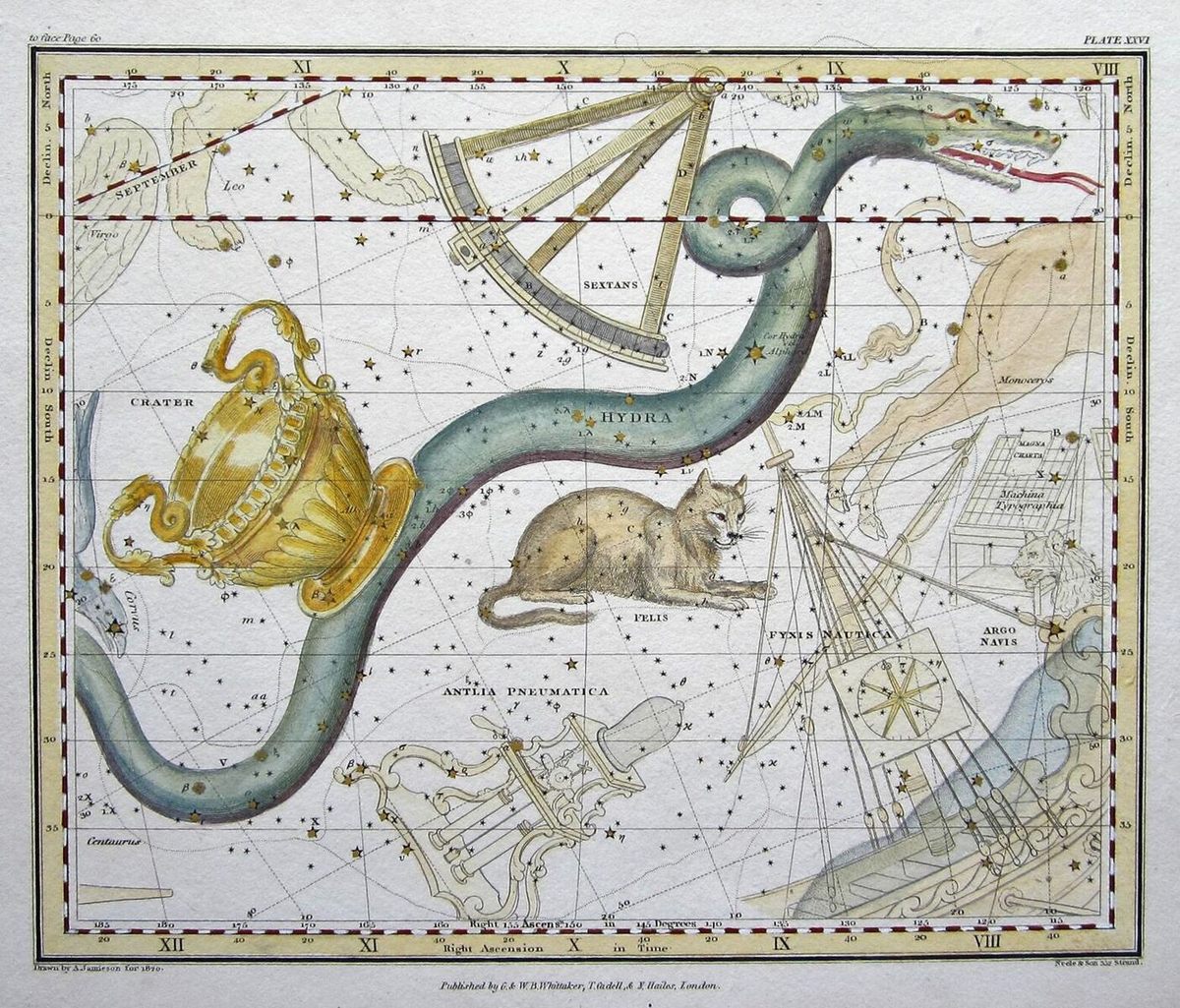

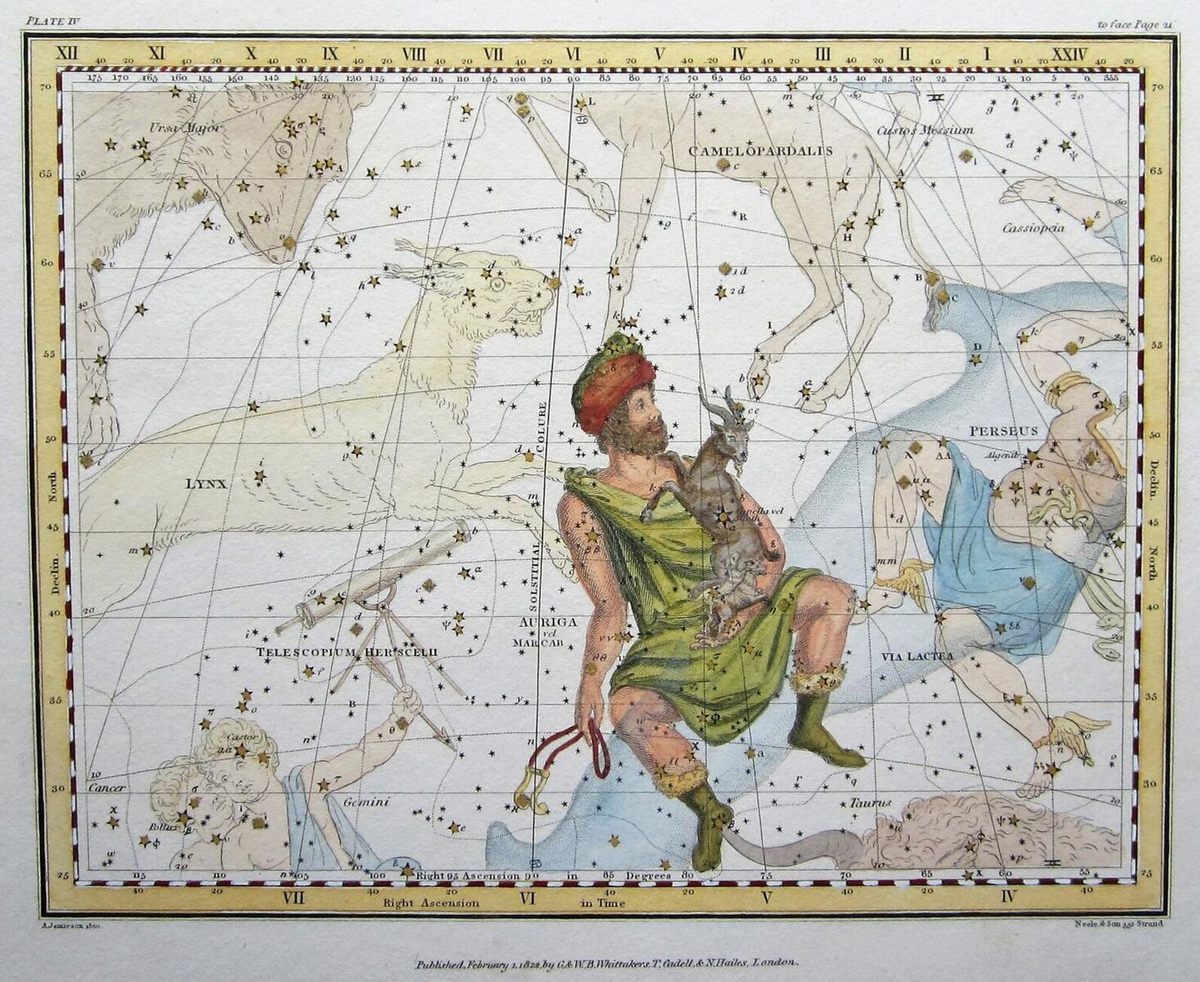

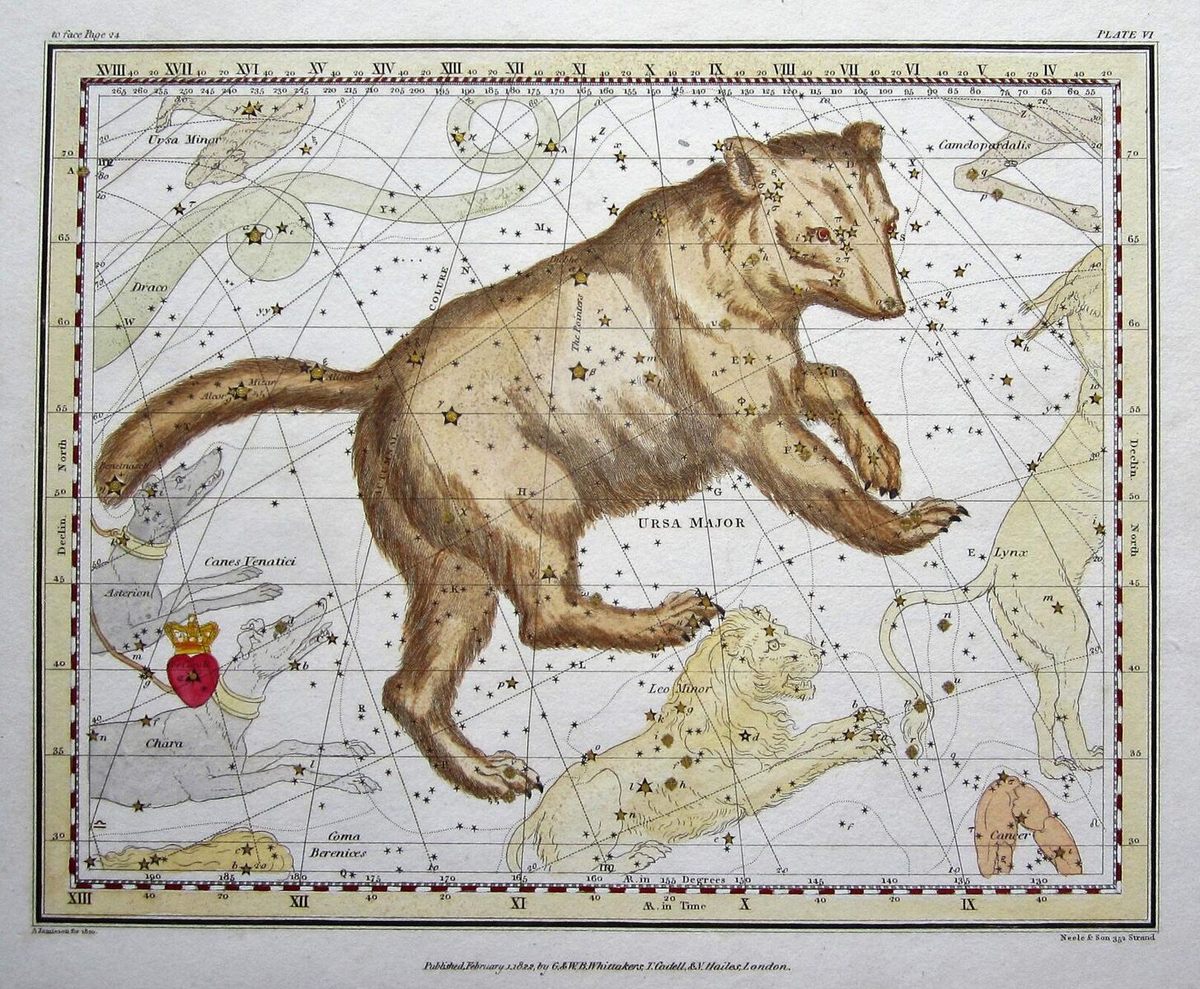

For a relatively modest fee, you could stoke your flights of fancy by flipping through a celestial atlas. These volumes placed an otherworldly landscape in the palms of your hands, and invited readers to search the sky for the constellations on its pages. When night fell—assuming you could glimpse anything through the smog and London’s cloudy weather—you could find crabs and bulls and mythological heroes far above your head.

Constellations were first described in ancient times, but it wasn’t until the early 17th century that these images were compiled into comprehensive atlases. In 1603, Johann Bayer, a German cartographer, partnered with the artist Alexander Mair to produce a hefty volume called Uranometria, which spanned the entire heavens. Its 51 copper-plate engravings wrangled stars into recognizable, wondrous creatures and scenes, often drawn from the ancient myths that gave the constellations their names.

They were drowning in whimsy, but that didn’t dilute the rigor. Star catalogues and visual atlases were intended for scholars and scientists, explains Matthew Edney, a professor of geography at the University of Southern Maine, and curator of the exhibition Art of the Spheres: Picturing the Cosmos Since 1600, at the Osher Map Library in Portland. The maps were annotated with coordinates, so astronomers could locate constellations in the sky and know whether they were looking in the right vicinity, even if there was some wonkiness with their telescopes. “They were meant to summarize, ‘This is the state of the knowledge,’” Edney says.

Then, as the 17th century wore on, “more and more people began making more and more celestial maps for a public audience,” Edney says. As printing prices fell, “cheaper and cheaper variants” sprung up alongside bigger, more expensive tomes.

The use of copperplate engravings was more cost-effective and forgiving than woodblock printing, which wasn’t well-suited to the level of detail the mapmakers aspired to. Unlike the black-and-white prints intended for scholars or the most erudite amateurs, the more popular maps could be lavishly colored. Scholars might have scoffed at these versions, Edney notes, because the richest of the colors—such as red pigments—could actually obscure details in the images.

Colorful plates weren’t ideal for scholarship, but as far as the public was concerned, they were spectacular to look at—especially when they depicted stars that the average person could spot without any expensive equipment.

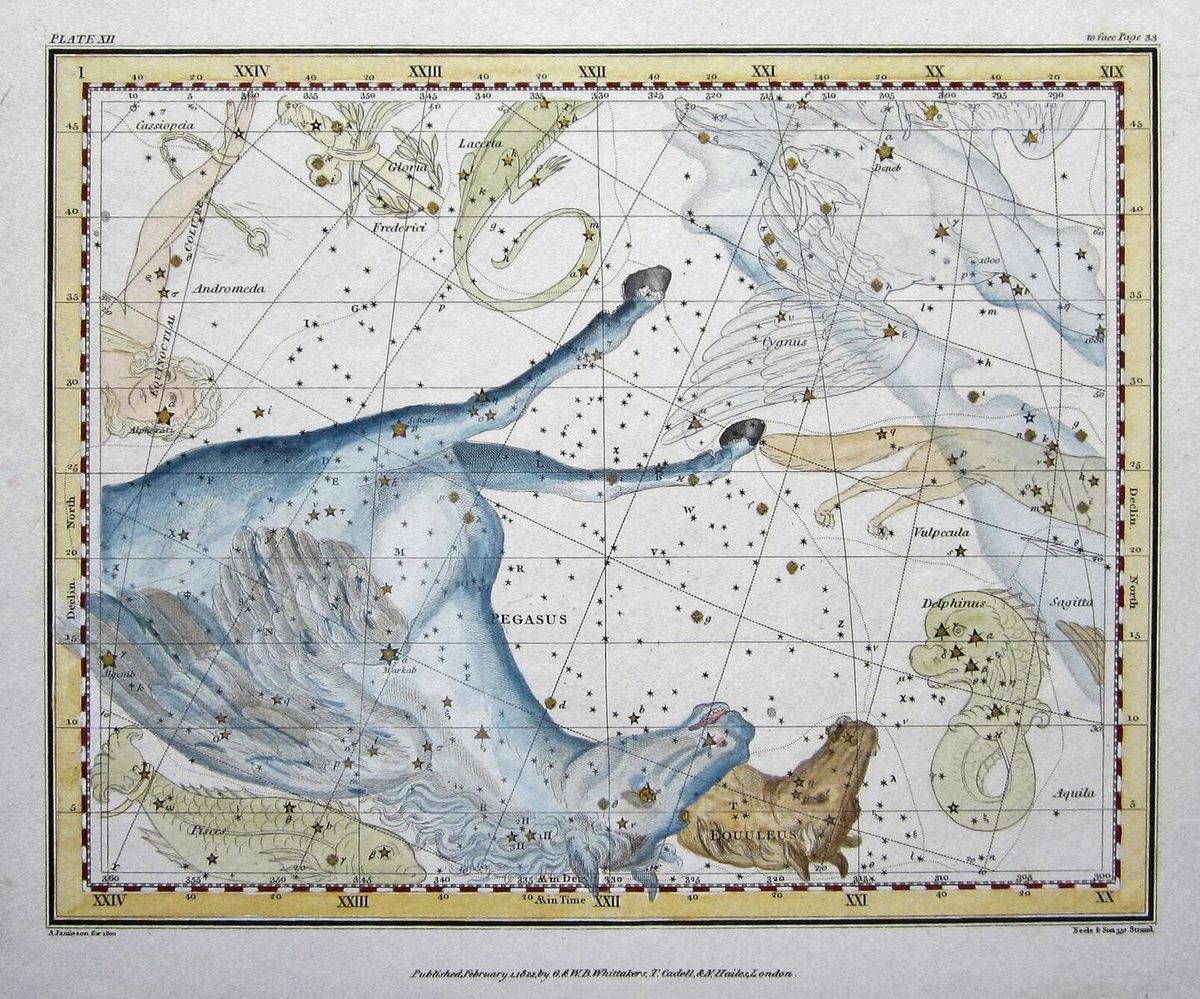

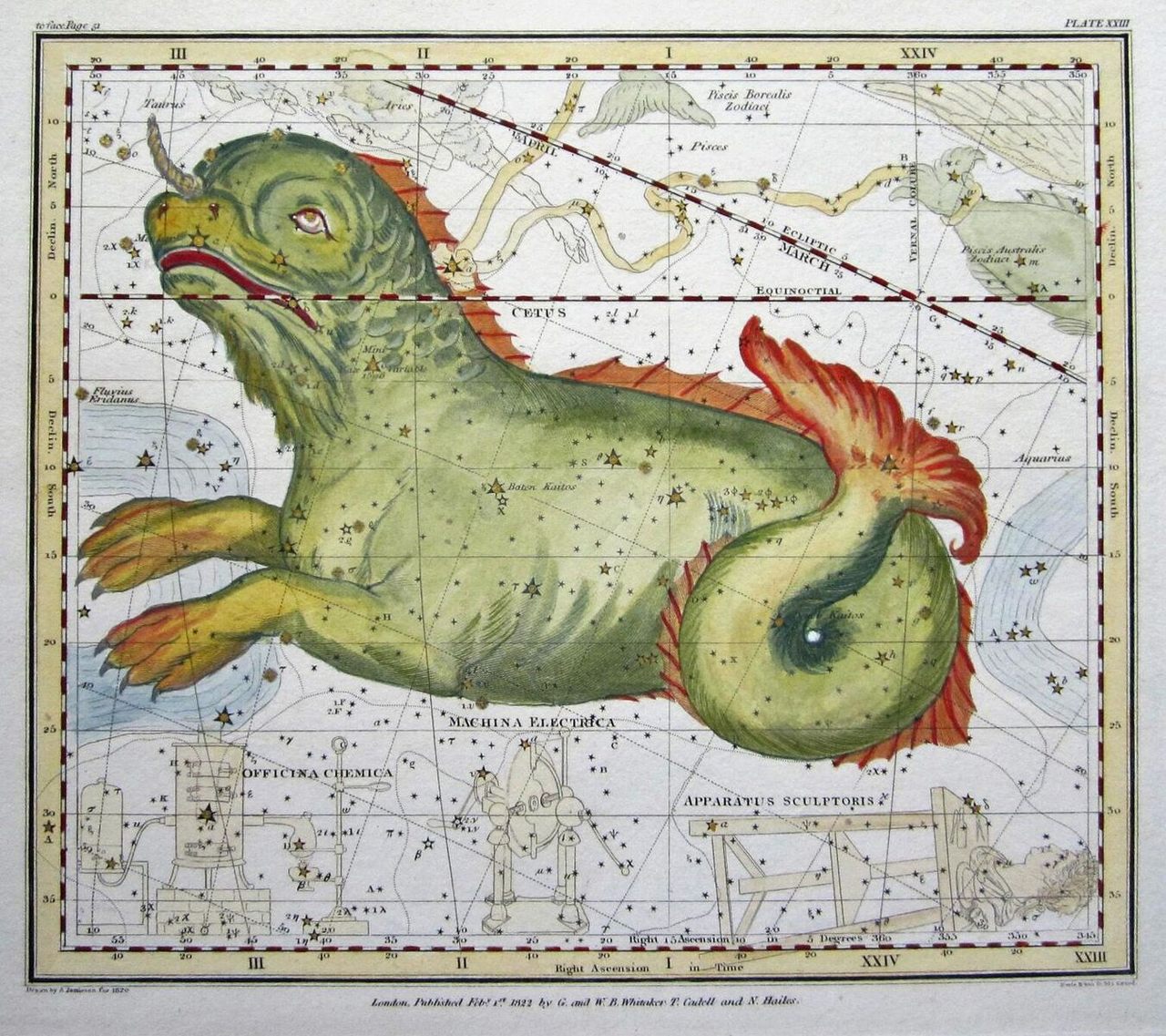

The Celestial Atlas, by Scottish schoolteacher Alexander Jamieson, was one of the ones designed for nonexperts. Printed in London in 1822, its 30 illustrations include only constellations that could be seen with the naked eye.

Measuring just nine inches by seven inches, it was easy to carry around. And the price was just 15 shillings for a black-and-white version (111 shillings and sixpence for color). This wouldn’t have been an impulse purchase, but it was far cheaper than its oversized forebears. (Jamieson’s volume is rare today, with a price tag to match: A complete copy is for sale at $3,201 on AbeBooks.)

Astronomy was a popular pastime, but it’s hard to say for sure how many buyers snatched up the volumes made for the general public, Edney says. “Archives just really haven’t survived,” Edney adds, “at least not that they’ve been found, catalogued, or made available.” We do know that Jamieson released a second edition just a few months after the first, suggesting it was flying off shelves. Striking aesthetic similarities appear in a set of constellation cards called Urania’s Mirror, printed a few years later. The cards were stippled with punched holes, to allow light to pass through and illuminate the constellations. This sincere flattery could be another sign that the first run had been a hit, and it is easy to see why. Atlas Obscura has more illustrations from Jamieson’s Celestial Atlas below.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook