Rediscovering the Newsletter That Inspired a Generation of Comedians

Billy Glason’s “Fun-Master Gag Files” influenced the joke industry for decades.

Joe Garden was at a barn auction in upstate New York when a mysterious box full of typed notebooks came up for bidding. “[The auctioneer] was describing them as ‘scripts,’” says Garden. It was only after winning the item that Garden discovered he’d acquired a rare collection of the Fun-Master Gag Files, a mid-century newsletter for the joke industry.

At first, Garden—a former features editor at The Onion who’s currently working as an antique and second-hand dealer—didn’t know what he was looking at. But as he started researching the Fun-Master Gag Files, he soon learned that its author, the comedy writer Billy Glason, had spent decades advertising monthly joke collections in the back pages of showbiz publications including Variety, Backstage, and Show Business. “Let a real professional train you!” promised one ad, alongside offers for Glason’s longer titles, such as How to Master the Ceremonies.

“He had a lot of services. He had the ‘Blue Book,’ which was not X-rated, but R-rated jokes; he had the ‘Blackouts,’ which were old vaudeville and burlesque sketches,” says Glason’s one-time student, Tommy Moore, who now bills himself as “The Professor of Fun.” In the 1970s, Moore trained under Glason in the older comic’s cluttered Manhattan apartment, even purchasing a $3,000, multi-volume “encyclopedia” of jokes from the man. “He was a cranky old guy, but he knew his stuff. He was Yoda,” says Moore, who would later devote a chapter in his book, A Ph.D. in Happiness From the Great Comedians, to Glason.

Glason got his start in entertainment at a young age. According to the 2012 book The Encyclopedia of Vaudeville, Glason was born in Boston in 1904 (although the vaudeville historian Trav S.D. contends that he may have been older), and started singing funny songs at small venues in his teens. He eventually became a staple of the U.S. East Coast comedy circuit, making a name for himself as an opening act who was tough to follow. “Look, you bring ‘em in and I’ll entertain ‘em,” he was often quoted as saying. Like many performers of the day, Glason’s act mixed music and Borscht Belt one-liners designed to entertain any crowd, every time.

As the years went by, radio brought a new type of entertainment into the home, endangering a number of vaudeville careers, including Glason’s. By the 1940s, Glason had made a name for himself as a joke writer, selling gags to anyone willing to pay for them. Eventually, the Fun-Master Gag Files were born.

“He told me, [a comedy career] is like opening a store, and the products are your jokes,” says Moore.

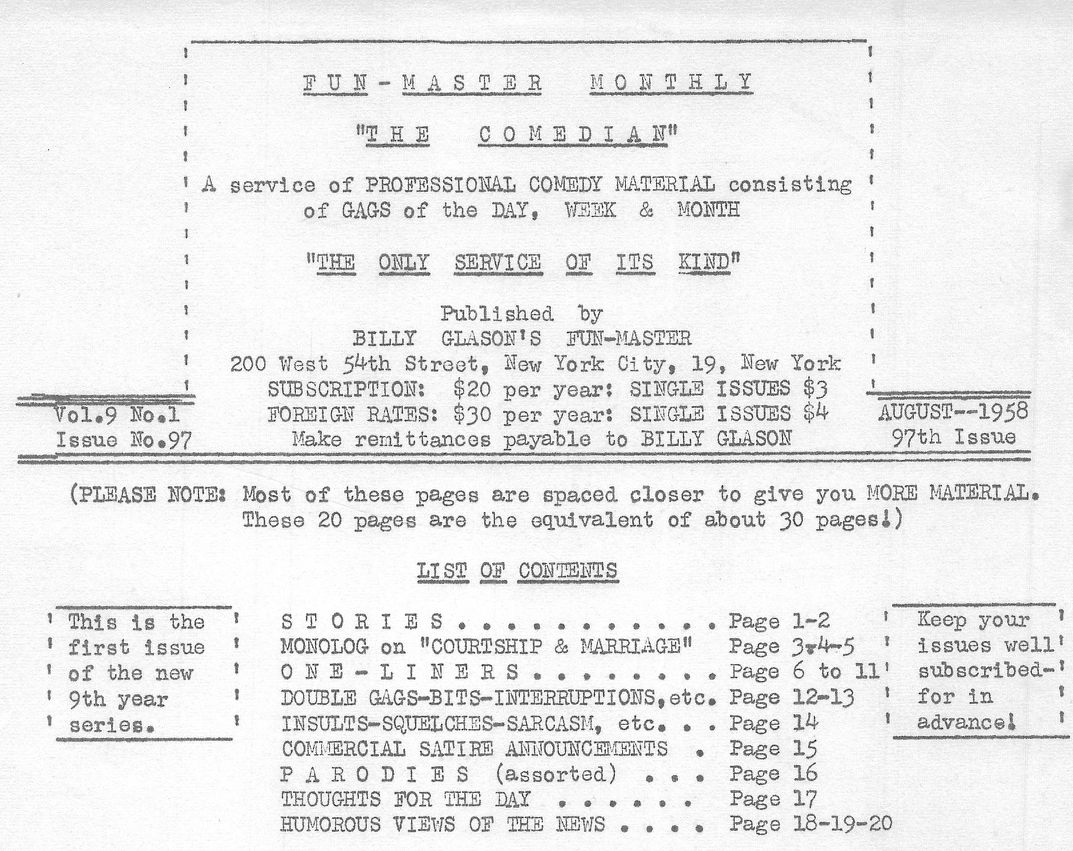

The monthly Fun-Master newsletter, which cost a few dollars per issue, contained sometimes as many as 20 pages of jokes, broken up into subsections such as “Stories,” “Insults—Squelches—Sarcasm,” and “Humorous Views of the News.” The jokes and gags within ran the gamut from cleverly convoluted yarns to snappy one-liners:

“I know a Texan who rides on a solid gold saddle. Every time he hits a bump, he strikes it rich!”

“Last week I played golf on a real crummy golf course. It had holes in it!”

“He’s a real hypochondriac. When he goes to a cocktail party, he stirs his drink with a thermometer!”

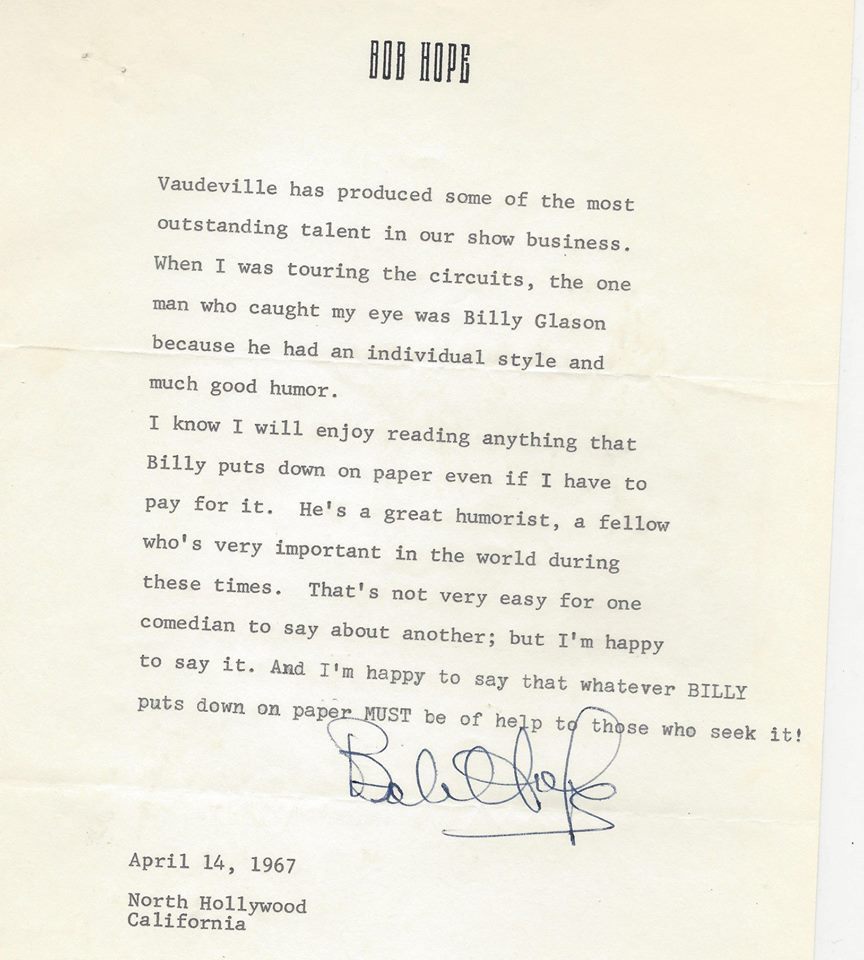

Thanks to Glason’s constant back-page advertising, Moore says the newsletter became a well-known industry resource. Famous comedians including Flip Wilson, Dick Gregory, Bob Hope, and Johnny Carson reportedly subscribed, or otherwise got jokes and training from Glason—even if not all of them wanted to admit it. “Jackie Gleason didn’t want to be on record as buying the Billy Glason gag files, so he had his writer, Harry Crane, buy them,” says Moore. “It was the writer who bought them, but it was Jackie Gleason who ended up with them.”

While Glason made a brisk business of selling jokes, he was against stealing another comic’s material. “He said, ‘these jokes that I’m telling you are basic, old format jokes.’ He said, ‘you can take these because these are public domain. You can take these and reword them to suit your own style,’” says Moore. While much of the material in the gag files was undoubtedly Glason’s original material, some of the jokes certainly came from comic traditions older than him. “In one of the ones I was flipping through, there was even a ‘How to get to Carnegie Hall’ joke,” says Garden. “Even in the late ’50s that one had whiskers.”

It wasn’t only comedians who took advantage of Glason’s jokes. Moore says that the newsletter was also bought by ventriloquists, DJs, and magicians. Anybody who needed some jokes in their act.

The Fun-Master newsletters were also often representative of the comedy of the day, for better and for worse. Jokes about nagging, controlling wives—or marriage as a prison sentence for men—abound, along with a number of ethnic stereotypes. Garden says that his auction haul also included another of Glason’s collections titled Pedro: A Compilation of Gags for the Spanish or Mexican Character, which he says is unsurprisingly filled with dated, offensive stereotypes and racially insensitive material. At the same time, during his career, Glason maintained a staunch insistence on working clean. “It used to really make him angry when people used profanity for the sake of getting a shock laugh,” says Moore.

It’s not clear when the first Fun-Master newsletter, originally titled The Comedian, was released. Judging by the dates on later editions, Glason likely started producing them in the late 1940s. All of Glason’s newsletters and collections were hand-typed and reproduced on a mimeograph. His apartment on 54th Street in Manhattan became a literal joke factory. “The front room of his apartment was his office, and it was legitimately waist deep in mimeographed copies that he was putting together for his monthly edition,” says Moore.

Glason died in 1985, and Moore says that he later learned from Glason’s daughter that most of the vaudevillian’s copious writings had been disposed of, making Garden’s find even more amazing. As Moore tells it, Glason only produced 26 copies of his complete encyclopedia, which collected editions of the Fun-Master along with other material, and to his knowledge only three of those complete works survive.

But even as the memory of Glason’s work has faded somewhat from the public consciousness, Moore sees his legacy in the work of later comedians like Steven Wright. “Any one-liner comedian is affected by what [Glason] put out for all of those years,” he says.

As for Garden’s finds, he plans to split up the physical collection among friends, many of whom are fans of comedy history. But first he made sure to digitize them all. “This is the last time this particular collection is going to be in one place. So the comedy historian, the comedy person in me is kind of [inspired to document it,]” he says. Call them cheesy, call them offensive, you just can’t call the Fun-Master newsletters forgotten.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook