For Sale: Legendary Photographic ‘Proof’ of Fairies and Gnomes

In 1917, two young girls with a camera pranked the world.

In summer and autumn of 1917, teenage Elsie Wright and her adolescent cousin, Frances Griffiths, borrowed a glass-plate camera from Wright’s father and tromped to Cottingley Beck, in West Yorkshire. They photographed each other on the bank of the stream and in the grass of a sun-dappled glen—and also captured some special guests.

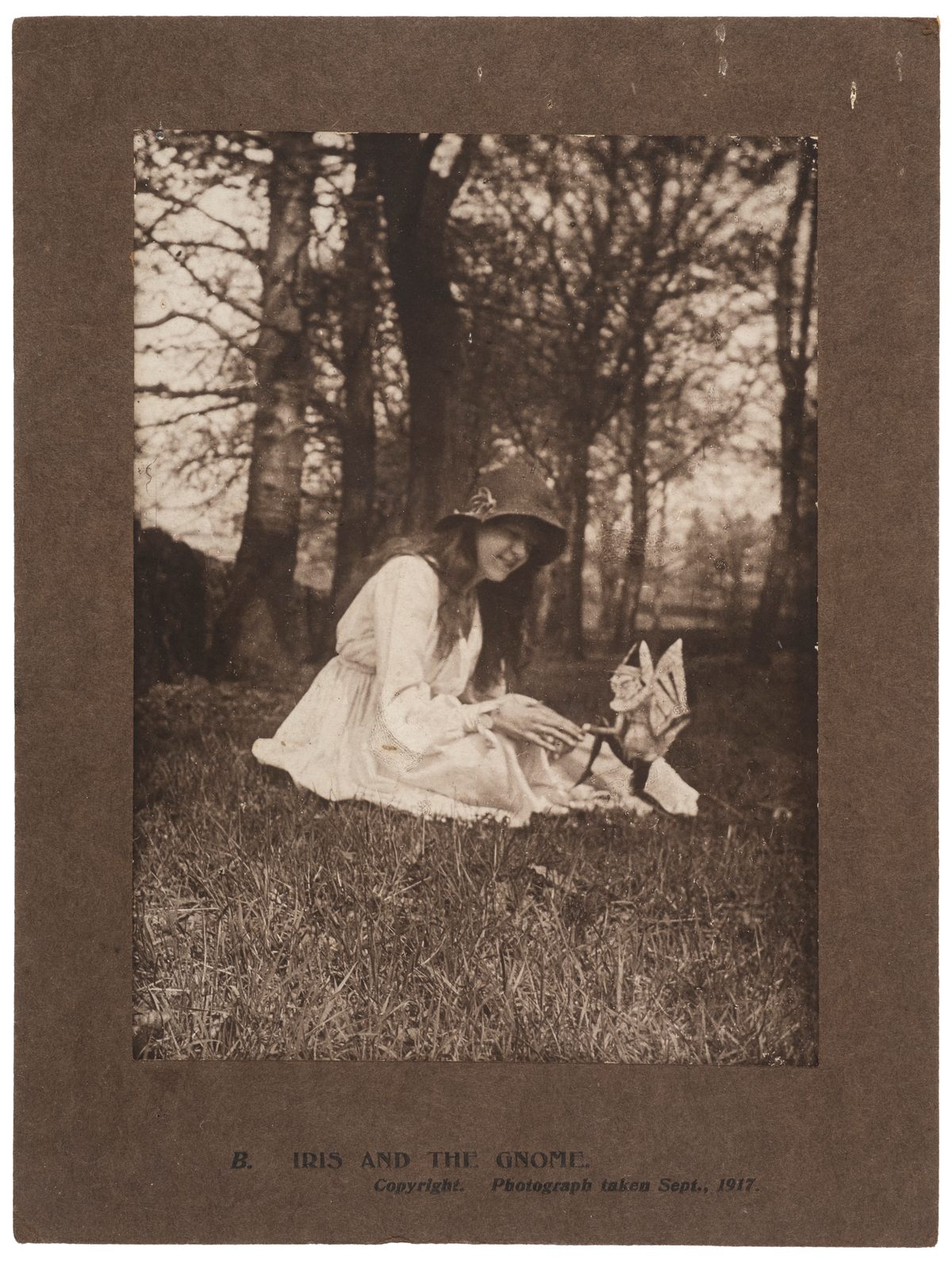

One image shows Griffiths, looking wistful, chin in hand, with a cavorting troupe of fairies. In another, a smiling Wright greets a gnome high-stepping through the grass.

For those inclined to believe in the existence of small, magical forest creatures, the photos felt like ironclad proof—the ultimate rebuke to the skeptics, clear as day. Some of the most ardent support for the veracity of the images, known as the “Cottingley Fairies,” came from Arthur Conan Doyle. Years after he had dreamed up Sherlock Holmes, the author campaigned for belief in Spiritualism, which boomed during and after World War I. Conan Doyle, who had lost his son Kingsley in the war, seized on the girls’ photographs as evidence of the mystical world. He compiled his arguments into a volume called The Coming of the Fairies. The pictures, he wrote, “represent either the most elaborate and ingenious hoax ever played upon the public, or else they constitute an event in human history which may in the future appear to have been epoch-making in its character.”

The cousins stuck to their story for decades. It wasn’t until the 1980s that an elderly Wright finally fessed up, after Geoffrey Crawley, a chemist and photography editor, embarked on a 10-part, nearly forensic analysis of the images in the British Journal of Photography.

The hoax, it turned out, wasn’t so elaborate. The cousins had carefully cut the creatures out of paper and staked them to the ground with little hat pins to create the illusion of floating. Hints of this sleight-of-hand were there, for those looking closely. The gnome’s belly, for instance, had a tiny hole where the pin poked through. Conan Doyle, for one, proposed that the little hole was a navel.

Now we have a fresh chance to be duped and charmed, when two of the photographs go up for sale at Dominic Winter Auctioneers, in Gloucestershire, on October 4. The auction house suspects that these prints were made in 1920, probably to be peddled at theosophical lectures. Each is expected to fetch between £700 and £1000 (roughly $900 to $1,300). Where Lots 921 and 922 will go next is a mystery, but they’re still magical reminders of a truly fantastic prank.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook