Behind the Walls of a Sports Bar, Remnants of Florida’s Early Years

How do you lose an entire elevator?

Picture the fresh, clean walls of a modern interior space. It’s hard to imagine they would hide anything special, but in the case of a former sports bar in St. Petersburg, Florida, some of them concealed a world of history, hidden for decades. When the walls came down during recent construction, they revealed century-old relics from a storied age: a telephone switchboard, a partial staircase, a double-sided fireplace, and an entire elevator with an elegant ceiling flecked with gold leaf.

The artifacts are long-forgotten pieces of the Detroit Hotel, built in 1888 along with a railroad station that helped establish the nascent city on Florida’s west coast. They were uncovered this summer during an extensive commercial renovation, when workers pulled away sheets of drywall around what appeared to be a storage closet.

“As we took the pieces away and pulled the walls down, we realized it was not just a storage closet and not just an elevator—it was original to the building,” says Dana Speer, spokeswoman for Segreti’s Hospitality Group, which is converting the downtown space into sister restaurants with a joint courtyard. “It was quite a fantastic find. It’s been like a treasure hunt in there, discovering the pieces of history that grew up around this building.”

There are many layers of history to peel back, as the site has undergone numerous alterations and renovations since the original Detroit Hotel stood as a beacon to travelers in the late 19th century. With 40 rooms, three-and-a-half floors, and a 70-foot tower, it offered rooms at one point for “$3.00 up”—including breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

The name of the hotel and the city of St. Petersburg reflect the geographic roots of the town founders: John C. Williams, a Detroit native seeking a milder climate for health reasons, and Peter Demens, a Russian aristocrat who anglicized his name after fleeing repression in his home country. In 1888, they entered into a contract to build the hotel near a railway depot to attract visitors to the area and its healthful climate.

Over the next century, the city developed a rich and varied history, as a resort town, a training base for troops during World War II, a site for baseball’s spring training, and a cultural center that includes the Salvador Dalí Museum. The Detroit Hotel drew visits from the likes of Babe Ruth, Joe DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe, and Janis Joplin, says Speer, who is tracking down historic photos to feature in a parlor-like space in the new restaurant.

The Detroit Hotel building evolved with its city through the years, from the removal of the tower and addition of two brick structures in 1911 and 1913, to a stucco facade and extensive renovations at the turn of the millenium that included removing hotel room walls to convert part of the site to condos. (It had closed as a hotel in 1993.)

“The Detroit is a special building because it represents so many different periods in our city’s growth and timeline,” says Laura Duvekot, a historic preservationist for the city of St. Petersburg. “It’s really exciting when evidence of the history is recorded in ways we didn’t even realize.”

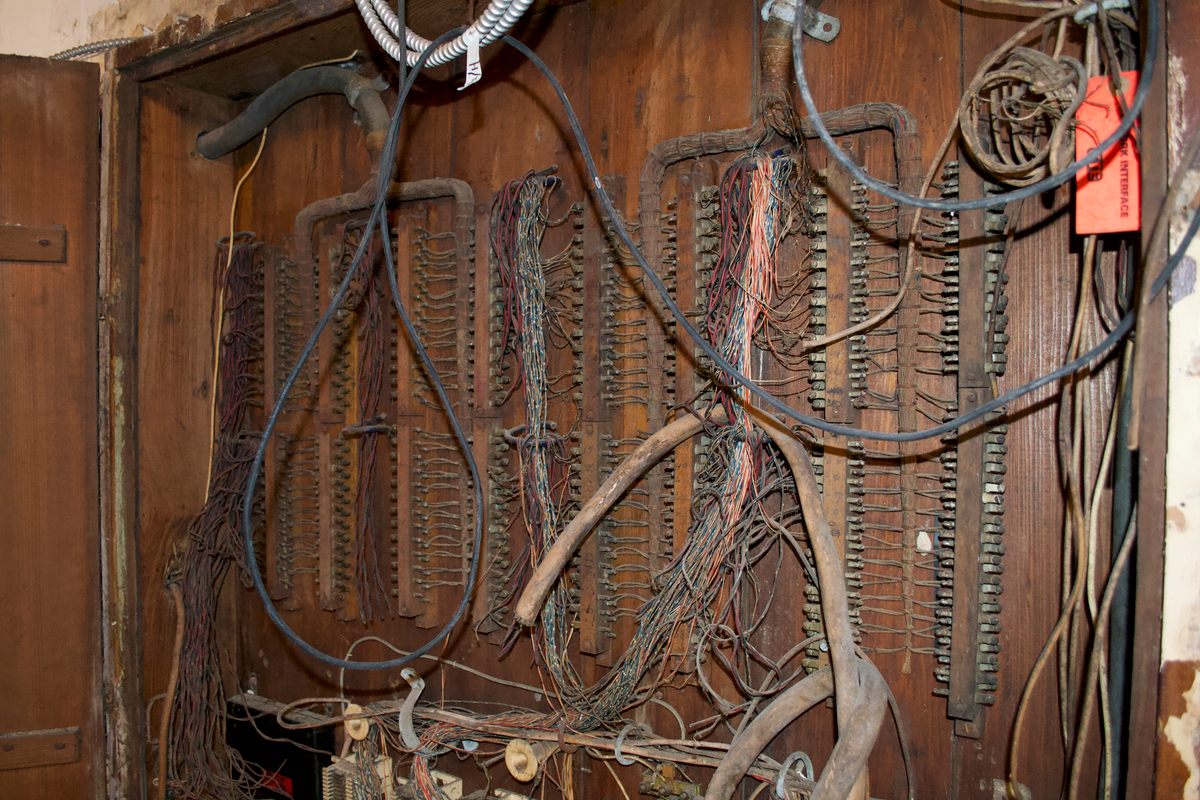

After the recent discovery of the elevator—a novelty in the late 1880s when its maker, the Warner Elevator company of Cincinnati, started manufacturing them—workers found its gears and motor in the floor. “They’re very cool-looking,” says Speer. “We’re going to have them polished up and encased in glass.” As more walls were torn down, the hotel’s original telephone switchboard was revealed as well. As tall as a person and almost as wide, it still bears handwritten room numbers.

Speer says the artifacts fit well into the steampunk aesthetic that was already planned for new space, which is slated to open in December. The Segreti team is keen to preserve and showcase the items in celebration of the city’s history, she adds. Plans call for a photo booth inside the antique elevator, simulated flames in the restored brick fireplace, and artisanal wallpaper accents based on small, hand-painted pieces thought to have been part of the original Detroit.

“We love what we’re doing there. We love bringing back a piece of St. Petersburg and a building that was the pride of the town for a long time,” says Speer. “To not restore it would be to lose something very special.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook