Central New Jersey Doesn’t Exist, But Don’t Tell Central Jerseyans That

Exploring what makes a region distinct.

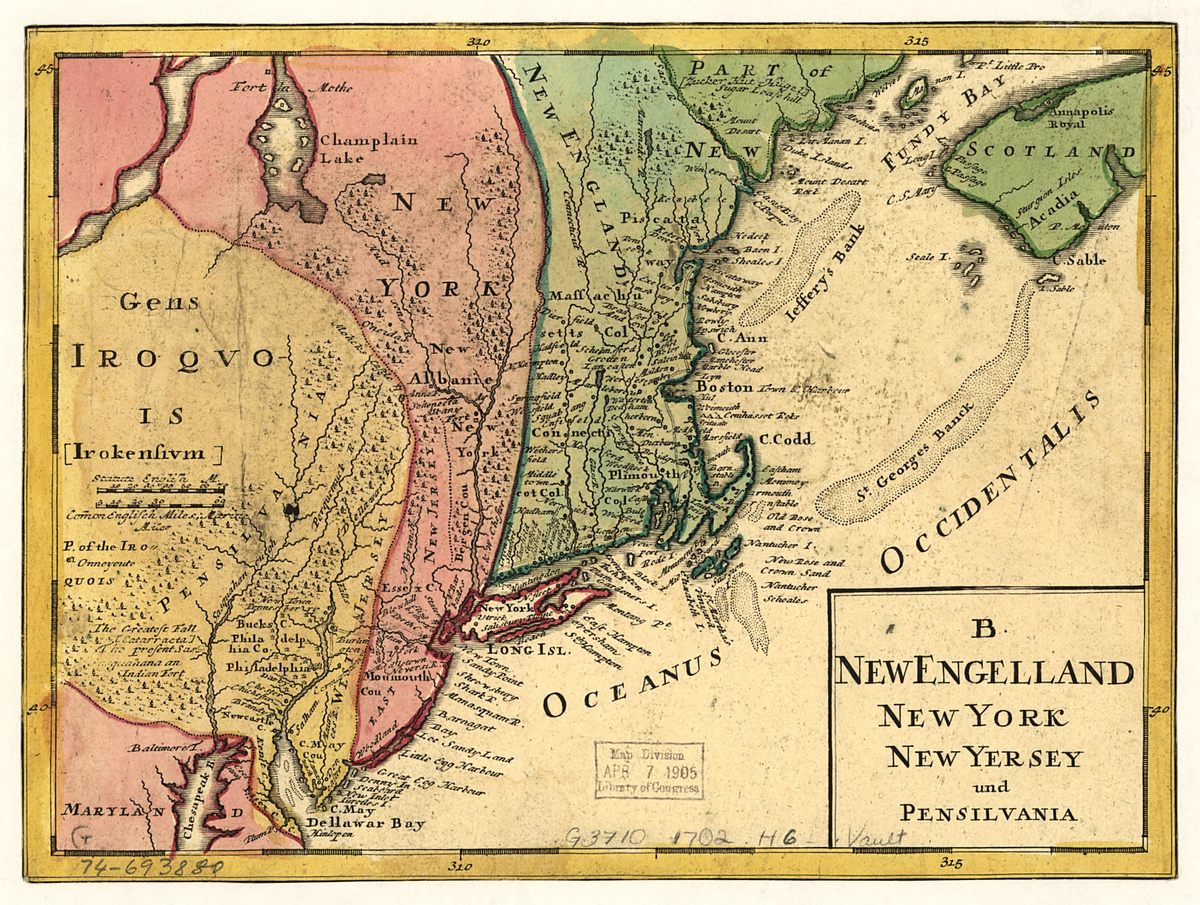

Throughout its entire history, after European colonization at least, the land now known as New Jersey has been split into two parts. Before 1702, it was two territories, known as East and West Jersey, with a diagonal border between them. After it was united as a colony and then a state, it maintained almost that exact same diagonal border, forming two culturally distinct if not officially recognized regions: North Jersey and South Jersey.

Yet for the greater part of a century, some have insisted that New Jersey has a third region. These folks are, overwhelmingly, those who actually live in the alleged region, which lies along that old diagonal border. What is Central Jersey? And, more importantly, what does it mean for the people who claim to reside there?

The first Europeans to stake a claim in the land now known as New Jersey were the Dutch, followed by some Swedes in the southwest of the territory. That was all ceded to the English with the Treaty of Westminster in 1674. In that agreement, King Charles II acquired a strangely shaped piece of land between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers. He ended up giving it to two loyalists, Lord John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret. In 1675, Berkeley, finding the whole collection of taxes thing to be annoying, sold his western half to some Quakers for £1,000.

For the next 30 years, there were two provinces: East Jersey, which was seen as an adjunct of the former Dutch land that’s now New York, and West Jersey, under the control of the Quakers, more closely tied to lands to the west, in Pennsylvania. Then as now, people argued over the actual borders between East and West Jersey; there were at least three major mapping projects, all of which ended up with a vaguely diagonal line that ran from Long Beach Island, on the Jersey Shore, to the Delaware Water Gap, give or take.

In 1702, East and West Jersey were united into one royal colony, named New Jersey, but the people of New Jersey have never really been convinced that their home colony, or state, is a single place. New Jersey maintained two capitals all the way until 1776: Burlington in the west and Perth Amboy in the east—even when these separate Jerseys weren’t supposed to exist. “It was still talked about as ‘the Jerseys’ even after unification,” says Patrick Murray, who has conducted polls about New Jersey for the Monmouth University Polling Institute.

The Industrial Revolution gave New Jersey, by then a state, a bunch of successful small cities: Paterson, Camden, Jersey City. The 1900s saw the rise of several more: Newark, Trenton, Elizabeth. Some of these cities are pretty good-sized, too; Newark today has more people than Orlando. Modern New Jersey is the most densely populated state in the country: 47th in area, but 11th in population.

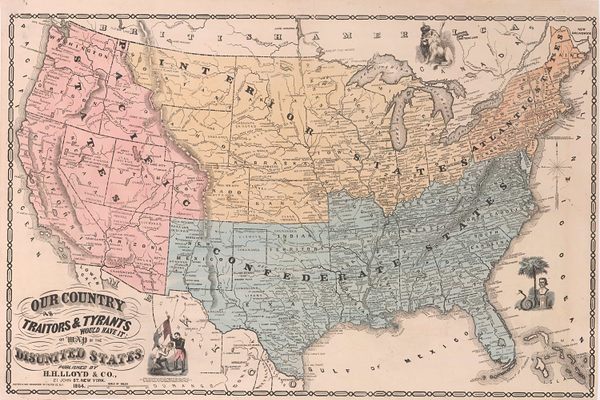

Despite that, New Jersey has never had—not in 1674, and not today—a singular hub city. From the moment King Charles II gifted a bunch of land to two of his toadies, New Jersey was defined by what it is not. It is not Pennsylvania, and it is not New York. It is the space in between the rivers, and immediately on the other side of those rivers are two huge cities, New York and Philadelphia.

The state today is so thoroughly shaped by its proximity to those two cities that, despite having nearly nine million residents, Nielsen does not consider it to have its own media market. The entire state is split between the New York City market and the Philadelphia market. There is, apart from a PBS station, just a single television station dedicated to New Jersey, and it is part of a network of small regional news channels, each of which covers a different section of … the New York City media market. In New Jersey, even the most local television station is from New York.

None of this is to say that modern New Jersey does not have its own culture, foods, language, attitudes, and sports—well, just a single team of its own left. (Thanks for the gift of the Brooklyn Nets! What a fun team.) But that culture exists within the orbits of New York City and Philadelphia, urban centers that have, not to be cruel, divided the state up. There is no linguistic difference between a New York City accent and a North Jersey accent, or a Philadelphia accent and a South Jersey accent. A great many New Jerseyans commute across one of the rivers to work in a city outside their state of residence. Sports fandom shows a clean division: Eagles fans over here, Giants fans over here. (Jets fans probably exist, too.)

They have distinct names for foods: Taylor ham/pork roll, sub/hoagie, Italian ice/water ice. Aside from that first one, which is a New Jersey creation, most of those other regional terms are borrowed from New York City or Philadephia.

Democrats often* control the state government, but there are two factions of the New Jersey Democratic Party, according to Murray. “The politics of the two places are fascinating,” he says. “South Jersey Democrats have a lot more in common with Democrats out in places like, say, Ohio, or Iowa, than they do with Democrats in Connecticut.” The South Jersey Democrats are noticeably more conservative than the North Jersey Democrats—in the same way that Philadelphia Democrats are more conservative than New York City Democrats.

New Jerseyans do distinguish themselves by geographic region. This isn’t weird; the same thing happens in California, Texas, New York, and just about everywhere else. In New Jersey, that divide is typically into either North or South Jersey. In 2008, Murray conducted a poll in which he asked New Jerseyans to choose whether certain towns are in North Jersey or South Jersey. He specifically chose towns along the perceived border between North and South, and, incredibly, the results follow, almost exactly, the line that officially separated East and West Jersey in the 1600s. That same line separates Giants fans from Eagles fans.

But things got a little weird. The respondents in the poll were given only two options: North or South. And yet those who hail from right around the border made it clear that those options weren’t acceptable to them. They, and they alone, claimed those towns as Central Jersey. “Central” wasn’t even an option; they wrote it in.

I spoke to several people who self-identify as Central Jerseyans to find out what makes the region they claim as their own different from the rest of the state. That’s the definition of a region, right? There must be something—language, food, geography, clothing, anything—that a neighboring region doesn’t have. No difference, no region, right?

The Central Jerseyans were very good-natured about me saying they’re liars. “I get why people say Central Jersey doesn’t exist,” says Brian Feldman, who grew up in Highland Park, near New Brunswick. “Because in my experience, where you’re from in New Jersey is mostly defined by whether you’re closer to Philadelphia or New York.” Feldman says that his hometown is within the orbit of New York City, but that it did not feel entirely defined by that association, the way a prototypical North Jersey town, like Hoboken or Newark, does.

“There is a type of person from North Jersey—we all watched The Sopranos—that’s kind of a typical North Jersey person, and we in Central Jersey are certainly not like that,” says Corey Hersh, from East Brunswick. “I know Central Jerseyans like to call themselves Central Jerseyans, mainly because they don’t want to be associated with the Philly culture of South Jersey and the New York culture of North Jersey.”

“My response is more a negative response than a positive one—it’s like, ‘We’re not this, we’re not this,’” says Katie Baker, from Pennington, near Princeton. Baker says that growing up, she was in the Philadelphia orbit. “I do call them hoagies, because Hoagie Haven is in Princeton,” she says. “That kind of goes against my whole cred that I’m not South Jersey.”

Central Jerseyans—rather like their state as a whole—define themselves by what they are not. They are not bridge-and-tunnel North Jerseyans. They are not cheesesteak-eating Philadelphians from South Jersey. So what exactly are they? That’s harder to put a finger on. A couple of people told me that they get both Philadelphia and New York City television channels: two of each major network. That’s interesting and weird, but maybe not enough to define a region.

There is (I think) some self-loathing involved in being a Central Jerseyan. New Jersey is a wildly stigmatized state; surely no other state, at least outside of Florida, is so widely mocked. Nationally known depictions of New Jersey—The Sopranos, Jersey Shore, The Real Housewives of New Jersey, On the Waterfront, Garden State—represent North Jersey, and not in a particularly flattering light.

Nationally, South Jersey has almost no pop culture profile, but it is still stigmatized—from within. As a Philadelphian who loves my home city but understands the national attitudes toward it, I’d suggest that South Jersey suffers from a double whammy: It is both New Jersey (bad) and Philadelphia (bad). “South Jerseyans really have animosity towards North Jersey,” says Murray, who is himself from South Jersey. “And what makes it worse for South Jersey folks is that North Jersey doesn’t have animosity for South Jersey; they just think it’s irrelevant.” South Jersey literally tried to secede from the state in 1980.

To say you’re from Central Jersey is to say, “Hey, whatever you know about New Jersey, that’s not me.” It’s a combination of pride and the acknowledgment of, or even agreement with, the negative view many people have of the state.

Yet negation is only half of a response. Take two small cities commonly claimed as Central Jersey: New Brunswick, on the outer edges of the New York City orbit, and thus North Jersey, and Princeton, on the outer edges of the Philadelphia orbit, and thus South Jersey. They must have something in common, right? Or is simply saying “Central Jersey” enough times enough to force it into existence?

There is one thing, at least. “I would say that it’s almost entirely college towns,” says Miles Read, who grew up in Princeton. New Jersey has a startling number of colleges and universities, but most of the largest or best-known fall under the Central Jerseyan’s definition of Central Jersey. There’s Princeton, Rutgers, Monmouth, Kean, and the College of New Jersey, among others. Both North and South Jersey have colleges, but the towns they are located in—Newark, Edison, Camden—haven’t really become “college towns.” They’re too close to New York and Philadelphia to have distinguished themselves in that way.

But in Central Jersey, where the pull of New York and Philadelphia is real but faint, a college in town can more clearly define the character of an area; there’s something about having a town full of academia that creates an outsized influence. The schools serve as cultural centers, with art and music coming to what would otherwise be too small of a town for national cultural figures to bother with. They usually have walkable urban cores. Baker told me that, though she went to Philadelphia fairly often, her go-to place to hang out and walk around was Princeton itself.

I think this all contributes to the Central Jersey mystique. But in reality, there isn’t anything especially different about Central Jersey. Everyone I talked to could, fairly comfortably, convince themselves that they’re really from North or South Jersey. “I’m totally a Central Jersey defender, but I don’t, like, disagree with anything you’re saying,” laughs Baker.

“Maybe we didn’t do a good job of carving out our own culture,” says Hersh.

“I have encountered this debate before,” says Feldman. “I’m not so stubborn as to not admit that they have a point.”

* Correction: This story was updated to make it clear that Democrats don’t always control the New Jersey state government.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook