The Historian of Hell and the Undead Takes on Dragons

Medieval expert Scott Bruce delves into the darker—and sometimes more hopeful—corners of human imagination.

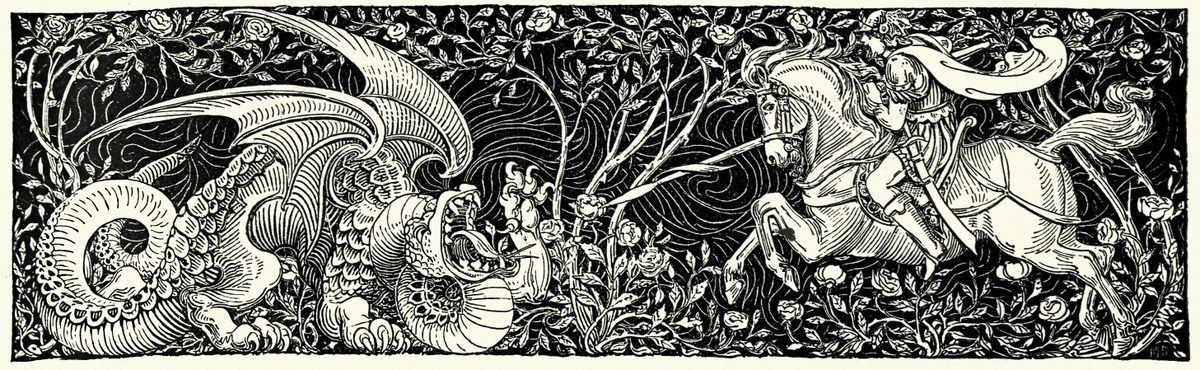

Scott Bruce knows a thing or two about what scares us. As a medieval historian at Fordham University, Bruce focuses on early monastic traditions, but he’s also the editor of Penguin Classics anthologies on hell and the undead. His latest collection, The Penguin Book of Dragons (October 2021), is a guide to the fantastic beasts and where to find them in the world’s mythological and literary traditions.

From 19th-century newspaper reports of monsters in America’s Wild West to ancient Japanese beasts that were more worried about giant centipedes than puny human weapons, Bruce explores how the idea of what a dragon is varies by place and time—something that it shares with our notions of the afterlife. And, like tales of hell and ghosts, dragon stories serve some purpose in this world, rather than the next.

Atlas Obscura spoke with Bruce about ghosts, gravedigging, and why we need dragons.

How did you start down the path to hell (and your other areas of interest)?

I came of age in the 70s and spent a lot of time reading comic books. It was back in the day when your dad could send you down to the corner store to buy him a pack of cigarettes when you were like six. My dad did this regularly, and would say “Here’s a quarter for a comic book.” I also gravitated toward fantastic movies that would be on television on a Sunday afternoon, like The Seven Voyages of Sinbad and Jason and the Argonauts. I loved myth, I loved fantasy, I loved sci-fi. I was also an avid Dungeons & Dragons player. I credit my literacy and any lecturing skills I have to being a dungeon master when I was young.

In grad school, I started studying monastic communities. Imagine my delight to discover the monks were also interested in ghosts and dragons and hell, all the imagery that would inform the literature I read.

You worked as a gravedigger for a time to put yourself through college in Toronto. How did that shape your work now?

It’s hard work. In the Canadian winter, the ground was often frozen so we’d use jackhammers. But at the same time, it brought out another aspect of me that I use as a historian: It made me very empathetic. I had to deal with people who were in mourning. And whether that’s somebody in your immediate present or you’re reading about someone a thousand years ago, empathy is the key to good history, at least the kind of history I do, because I take seriously the things that these people think and feel. Behind all this belief is feeling.

Why do you think stories of hell and ghosts are so universal?

The undead and hell are connected. Every culture thinks about them. There is no purely nihilistic culture that denies an afterlife, though there may be individuals within a culture who do. For most people, there’s this hope that the story continues, and then we have to populate that with ideas about how it continues. That act of imagining all comes out of our own uncertainty about what happens at the end of our story, and what the new story, if there is one, will be. Ghost stories are not static, they change, their meaning changes, and they often teach us something about what’s to come. The hell one is very similar. Something like 54 percent of Americans believe in hell, a place where people are punished for their sins—but only three or four percent believe they’re going there, which I think is very telling.

What about the near-universal cultural references to dragons?

I think dragons are there because they are the creature against which we measure the virtue of our heroes. In Western culture, where martial prowess is the key thing, whether they are soldiers or saints, you need something that is superhuman against which to fight. But in Eastern cultures, it’s also the measure of courage. In one of the Japanese stories in the book, a dragon comes to a warrior and says, “Look, my family needs your help because there’s an even worse monster, a giant centipede that’s going to eat us all, and I know you are a brave and virtuous human being. Can you save us from it?” and that also bears the measure of the hero’s generosity, because he does go and save them. We need dragons in a sense because they provide us with a rod against which we measure the heroism of our heroes.

What do you make of the ubiquity of dragons in pop culture today, from Game of Thrones to the cute dragon emojis on our smartphones?

It began a hundred years ago, when dragons were effectively domesticated. In the late 19th century, people started writing children’s stories where the dragon in the story is friendly and nice. [Now] they’re everywhere. You can’t escape them. I think now that we’ve mastered them, we feel like we own them.

There’s a bigger thesis that can be made here, in that the 20th century really saw the domestication of all sorts of imaginary creatures that we used to think of as frightening. Angels used to be considered extremely frightening. When my medieval monks encounter angels they are terrified of them. And angels are usually angry, too. They’re not nice. Similarly, vampires used to be frightening and now they’re teenage love interests. [With dragons], the coolness factor is that they’re big and potentially scary, but they don’t have to be scary if we can control them. So dragons are now like your really fancy, big dog.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook