The First Scientist to Study Dinosaur Footprints Thought Giant Birds Made Them

Edward Hitchcock clung to his theory, even when paleontologists said it didn’t fly.

Gigantic flightless birds roamed New England in the Jurassic. At least that was the hypothesis proposed by 19th-century geologist and natural theologian Professor Edward Hitchcock, based on the thousands of fossilized three-toed footprints he found all over the Connecticut Valley. Native Americans and European colonists had known about the strange tracks for hundreds of years, of course. Some settlers even jokingly ascribed them to Noah’s Raven, the bird that had been released after the biblical deluge to find dry land. Professor Hitchcock, however, claimed to be the first person to study them scientifically.

Born in 1793 in Deerfield, Massachusetts, Hitchcock was eager to learn from a very young age. Growing up, he was often hindered in his studies by bouts of illness, culminating in a case of the mumps in 1814 that left him temporarily blind.

Believing that a closer connection with nature might alleviate his ailments, Hitchcock took extended walks in the sandstone valley that splits central Connecticut and Massachusetts. These excursions ignited within him a deep love and fascination with the natural history of the region and he soon became an expert on the valley, despite having no advanced education beyond the basic schooling of the time. He eventually gained so much renown as an authority on local geology that the Trustees of Amherst College in Massachusetts appointed him Professor of Natural History and Chemistry in 1826.

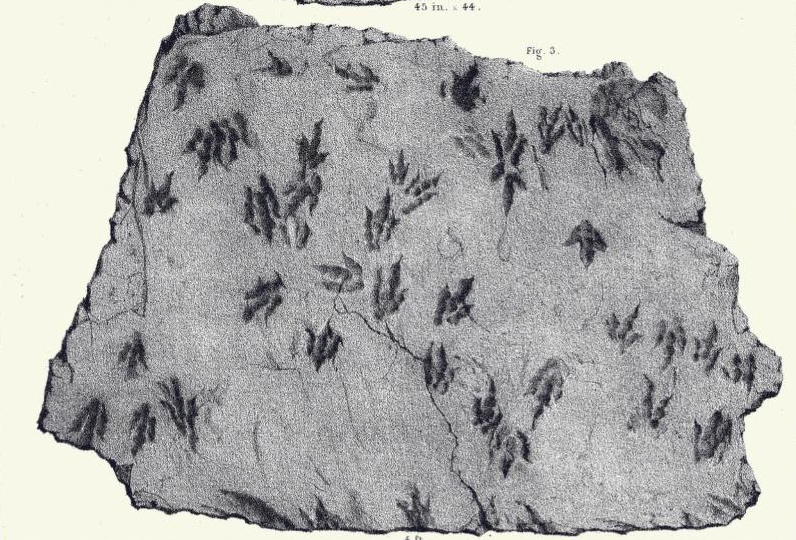

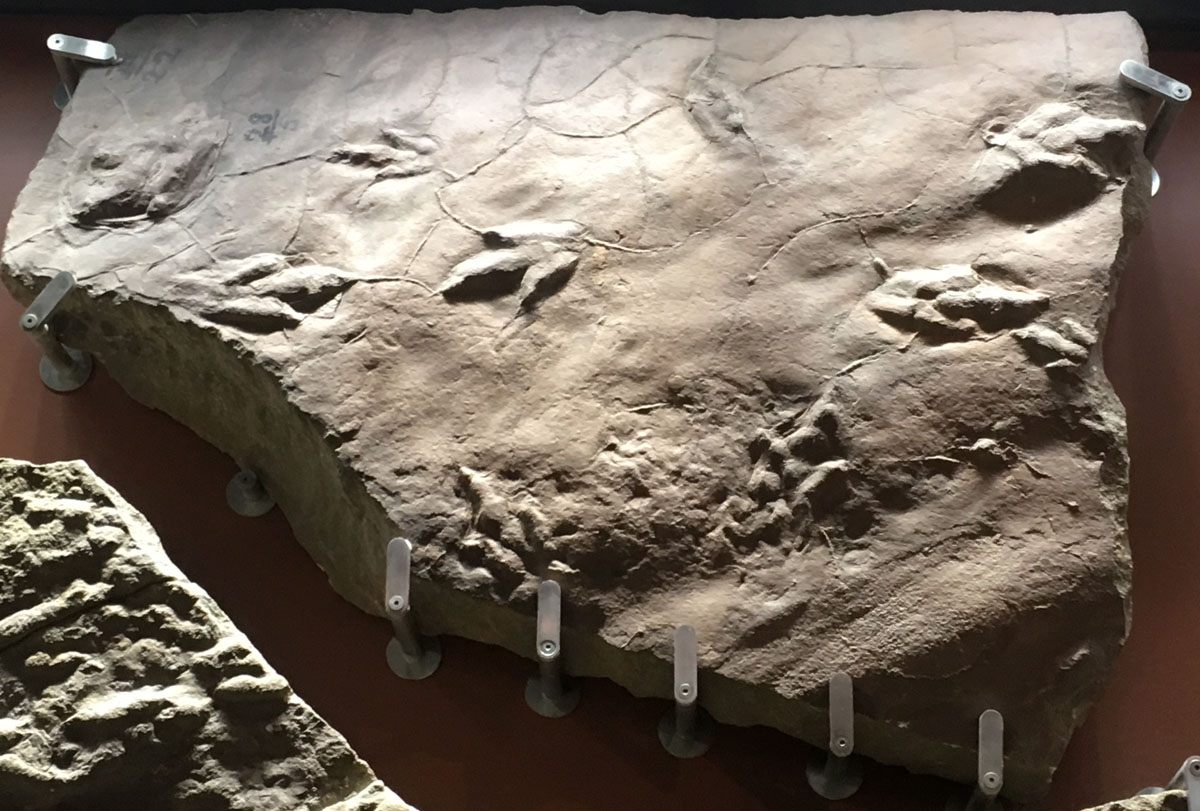

Hitchcock first learned of his beloved valley’s fossil footprints in 1835 from a physician, Dr. James Deane, who wrote to him about some flagstones he had seen that bore gigantic turkey-like tracks. After gazing upon these fossils himself, Hitchcock became obsessed. He visited sandstone quarries all over the valley, discovering tracks everywhere. He amassed a huge collection of footprint slabs and stored them in a dedicated room at Amherst.

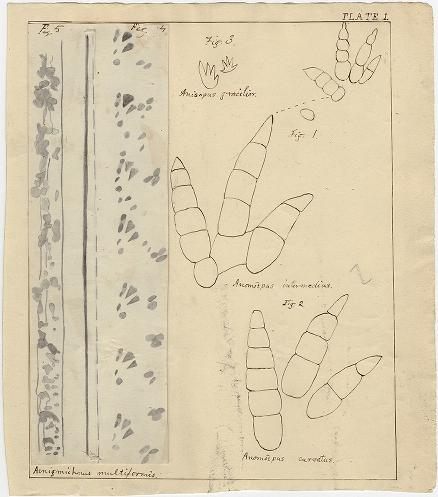

He identified several distinct “species” of tracks and gave them their own scientific names, including Anomoepus, Otozoum, and Eubrontes, the latter of which is the state fossil of Connecticut. It should be noted that these names refer specifically to the tracks themselves and not to the animals that made them since it is difficult, if not impossible, to determine precisely what prehistoric creature made a set of fossil footprints. Based on their distinct clawed, three-toed shape, though, Hitchcock hypothesized that these tracks had been made by giant flightless birds.

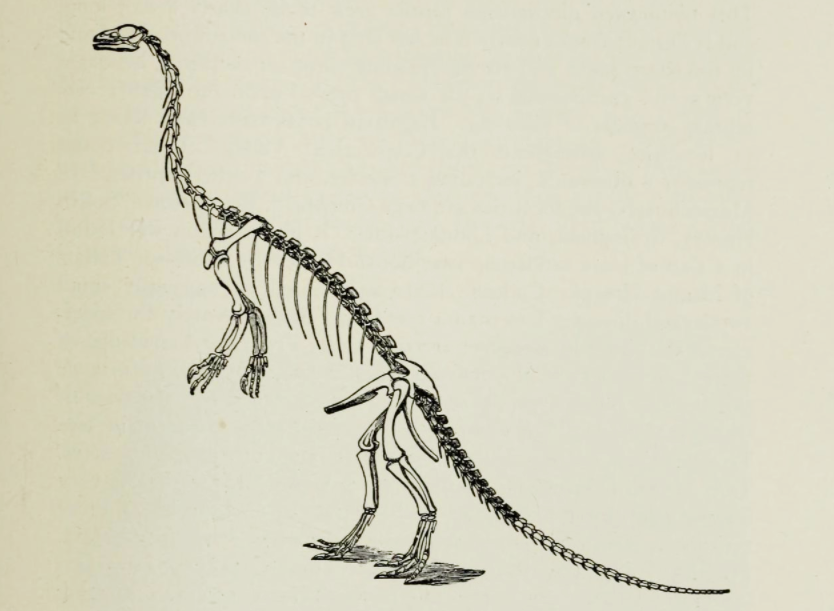

We know now that Eubrontes, Anomoepus, and their fellow footprint species were made by dinosaurs and other reptiles from the Jurassic period. But the term Dinosauria was unknown at the time that Hitchcock began his studies, and would not appear in the scientific literature until seven years later in 1842 when it was formally coined by British paleontologist Sir Richard Owen. Even then, Owen depicted dinosaurs as sluggish, lumbering, quadrupedal reptiles, a poor fit for the narrow, agile-looking, and clearly bipedal tracks in the Connecticut Valley.

Hitchcock coined the term Ornithoichnology, the study of “stony bird tracks”—later shortened to Ichnology—to describe his specialized area of study. Though the professor focused only on footprints, today this field has expanded to encompass the study of fossil burrows, eggshells, dung, and other traces of animal behavior.

To Hitchcock, birds as the track originators made far more sense, even if contemporary birds of this size were unknown. In 1843, he found what he believed to be vindication for his belief when he heard about the discovery of bones from nine-foot-tall moa birds that had only recently gone extinct in New Zealand.

As time went on and more dinosaur skeletons were unearthed, scientists began to describe them as more active, upright and, yes, relatively bird-like. By the 1850s many paleontologists—including Richard Owen, with whom Hitchcock was good friends—came to believe that the Connecticut Valley prints had been made by these saurians. Hitchcock, however, clung to his theory that the tracks had been made by fully modern avians. In 1858, he advocated for his theory in a large volume called Ichnology of New England and would hold this view until he died in 1864.

Nancy Pick, author of Curious Footprints: Professor Hitchcock’s Dinosaur Tracks and Other Natural History Treasures at Amherst College, provides some insight on his stance. “I still believe that Edward Hitchcock clung stubbornly to his ‘gigantic ancient bird’ idea because he had a poetic soul,” says Pick over email. “He wanted to believe that God’s creations were beautiful, not monstrous, and he also wanted them to fit into his biblical view of the world. There were no dinosaurs on Noah’s ark!”

Ironically Hitchcock’s bird hypothesis was, in essence, not too far off the mark since one branch of dinosaurs contained the ancestors of modern-day birds.

Though his curiosity about the natural world drove his scientific career, his true passion was always religion. He was raised a devout Christian and remained so throughout his life. Of his beliefs, Pick says, “Hitchcock refused to accept the cruel concept of ‘survival of the fittest,’ even though he admired Darwin and corresponded with him.” He believed instead that God had created and destroyed several ages of animal life, one after the other. Although the label was not used widely during his lifetime, it wouldn’t be a stretch to describe Hitchcock as a creationist.

Hitchcock was no dour New England Puritan, however. He took great joy in studying natural history, believing that it elucidated divine creativity in nature, an idea that he expanded upon in his 1851 book The Religion of Geology and Its Connected Sciences and in his religious lectures to the students of Amherst. “By bringing before the imagination the most brilliant objects of the natural world,” he wrote in his lecture, “The Triumphal Arch of Summer,” “we get some faint conception of its magnificence; or rather, we learn that the most splendid scenes of earth are only faint emblems of the New Jerusalem and the Glory of God which forms its light.”

“I believe he saw God’s hand everywhere he looked, whether he was gazing at animal tracks, plants, or geological formations,” Pick says. “Like many scientists of his era—though he came at the tail end of it— he was an extraordinarily acute observer of natural phenomena who continued to place all his observations within a religious framework.”

Even if his idea of birds as trackmakers was ultimately incorrect, Hitchcock contributed a great deal to the developing field of geology. Based on fossil plants he and his colleagues found in the valley, he deduced that the climate in New England in the Jurassic period had been warm and tropical with alternating wet and dry seasons. He also discovered that the sedimentary rocks of the valley had formed on an ancient delta floodplain, and that Eubrontes and other fossil footprints had been laid down on their muddy shores. He also produced the first geological map of Massachusetts which “even today is considered an impressively accurate guide to the state’s basic rock formations,” Pick wrote in her book Curious Footprints.

In his diary, Hitchcock wrote that “Should (Amherst) College pass into the hands of men who reject this system [Evangelical Christianity], I want them to feel that they have no right to use my collections but should give them up to my heirs.” Luckily this wish was not heeded and the professor’s vast and diverse collection of Connecticut Valley dinosaur footprints is on full display for everyone to enjoy at the Beneski Museum of Natural History at Amherst.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook