Found: A Natural Egg-Incubator in the Deep Ocean

Who knew hydrothermal vents make such great nurseries?

For deep ocean dwellers, everything seems to take a long time. Take the Pacific white skate (Bathyraja spinosissima), a pale, cartilaginous fish that can live nearly 10,000 feet down. Once a skate has laid a fertilized egg—in a tough case called a “mermaid’s purse“—it can take four years of incubation before a new skate emerges. But according to a new study, the creatures have a way to speed up the process.

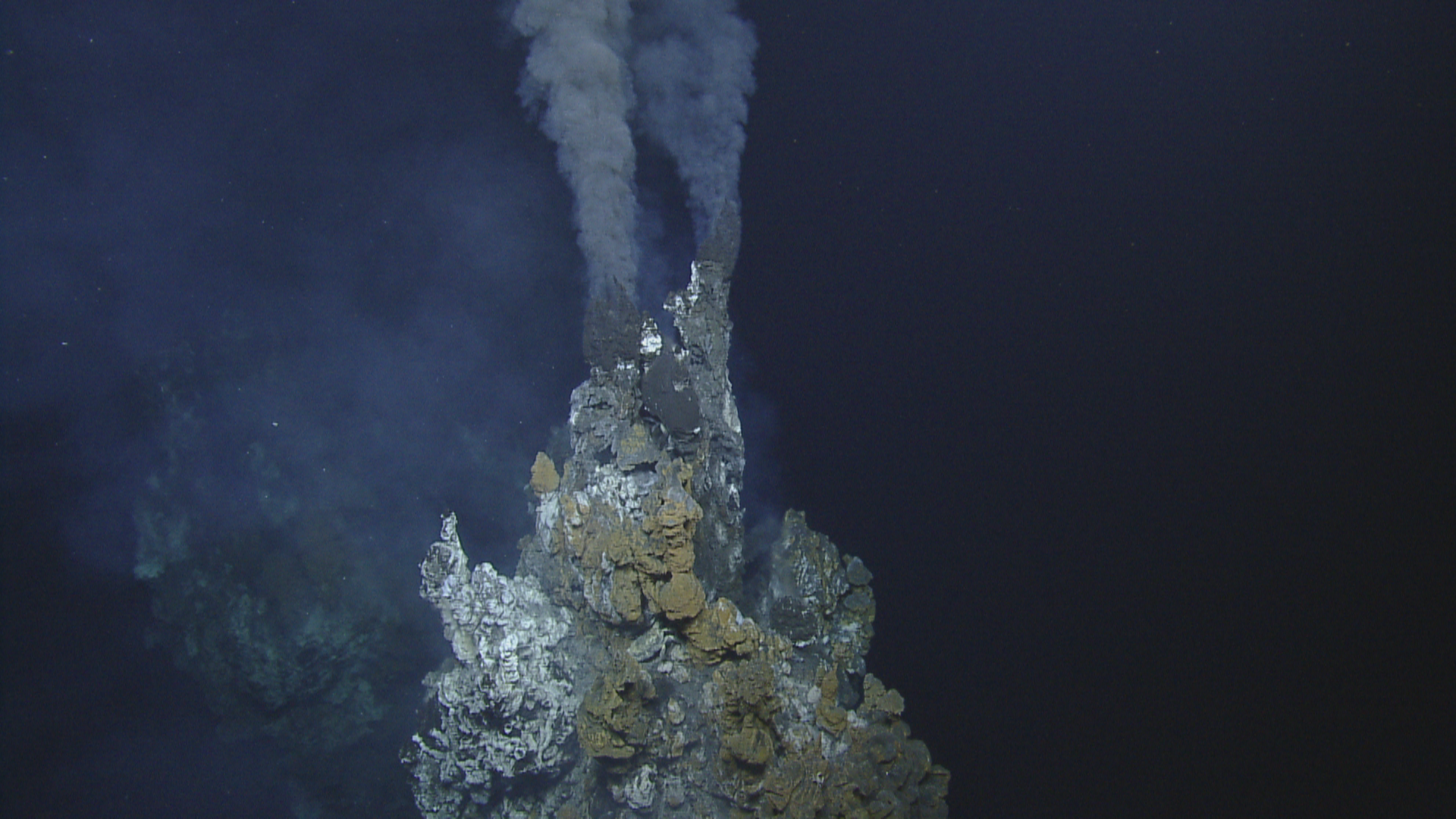

In 2015 a team of scientists from the University of Rhode Island (URI) and the Charles Darwin Research Station were exploring the deep seafloor in the eastern Pacific Ocean, near the Galápagos Islands, when they noticed a large number of skate eggs lying close to hydrothermal vents, fissures in the seafloor that produce plumes of water heated by geothermal activity below.

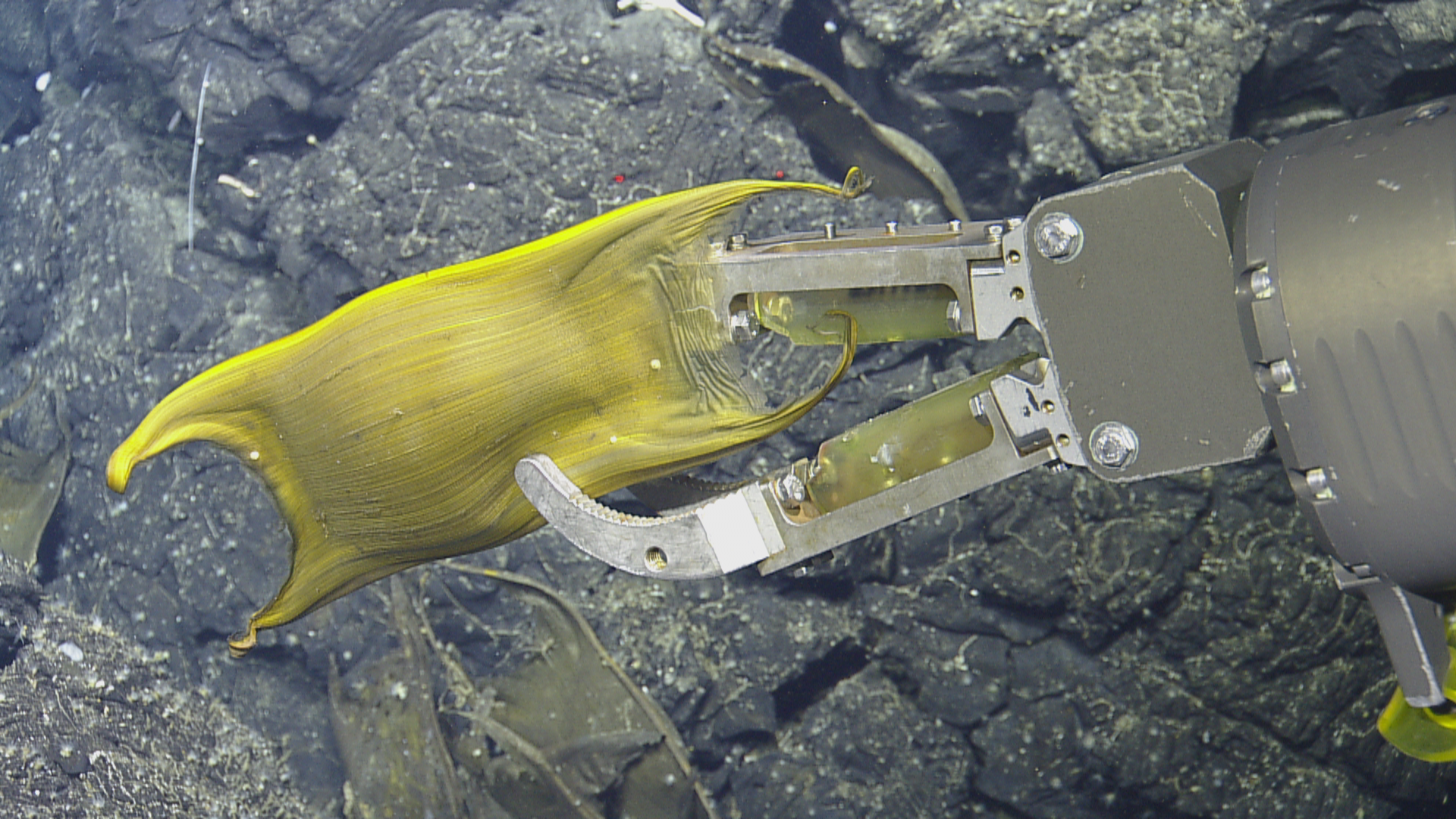

“We were on a really deep dive in a hydrothermally active rift valley, with walls 30 meters tall on either side, and the ROV [remotely operated vehicle] was meandering back and forth looking for vents,” said Brennan Phillips, an oceanographer at URI who led the exploration, in a statement. “We started noticing all these egg cases, and we recorded their location and collected a few but then just kept going.”

The ROV gathered data on the location of 157 egg cases in total, and observed that more than half of them were seen within 66 feet of hot vents, and nearly 90 percent were in places where geothermal activity warmed the surrounding water.

“The eggs weren’t right next to the active vents, because the water can get so hot—hundreds of degrees—that it would kill them,” Phillips added. “We found most of them in lukewarm water not far from the vents and near some extinct vents.” As reported in a study published this week in the journal Scientific Reports, the team concluded that skates intentionally place their nurseries near vents to accelerate the development of the embryos.

According to the study, it is known from fossil evidence that some dinosaurs laid their eggs in soil warmed by volcanoes, a practice also employed by Polynesian megapode birds. But this is the first time that such a strategy has been reported in the ocean. Researchers now hope to identify and protect these underwater nurseries.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook