This Ancient Egyptian Textile Is Hanging By a Thread

Only 20 khayamiya artisans are left, in one dusty alley in Cairo. Can e-commerce save them?

Behind a dense curtain of colorful patchwork, Ekramy Al Farouk begins stitching the quilt he started days ago. He hopes to sell the finished product later today. But as he learned from his father—who learned from his father—the laborious, painstaking process of khayamiya can’t be sped up.

It’s not unusual for one piece of this ancient Egyptian art—a decorative appliqué textile made nowhere else in the world—to take weeks to complete. Patient artisans like Al Farouk, 44, who began stitching when he was 12 years old, train for years to master its intricacies.

“Learning khayamiya goes through different levels,” Al Farouk says. “It takes a lot of time to learn even the simple pieces, and I had to learn those before the professional ones.”

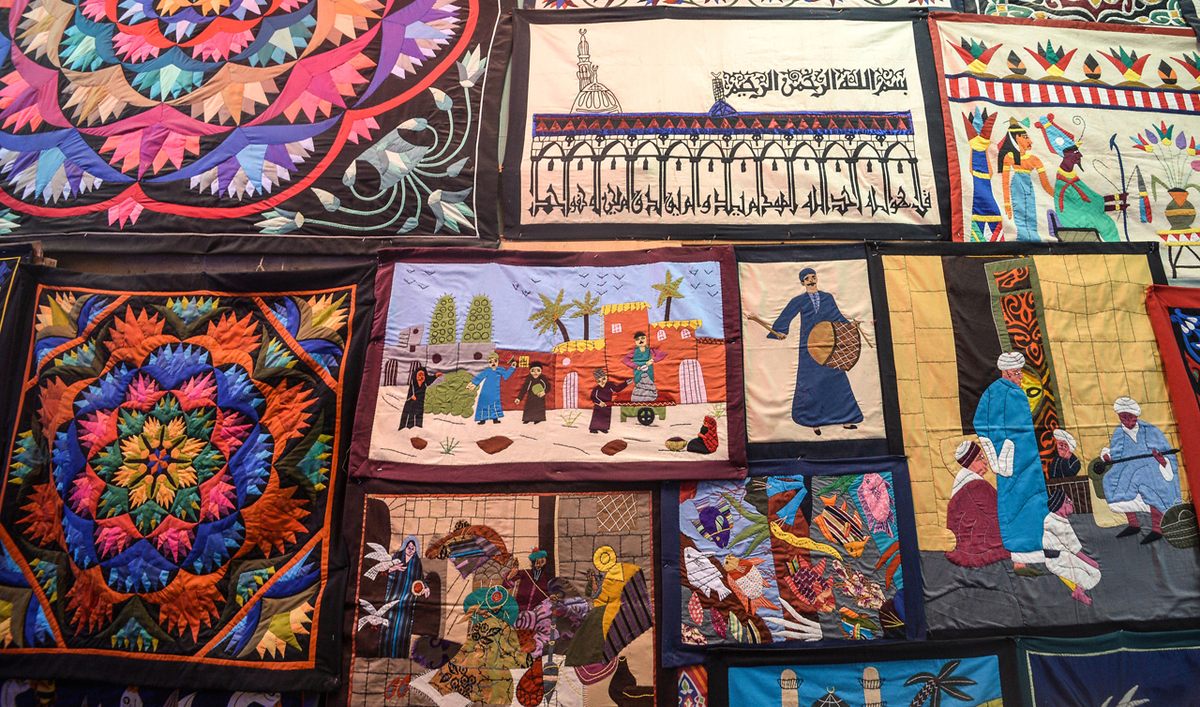

Generations of khayamiya artisans like Al Farouk have plied their trade in this dusty alley—a quiet stretch of storefronts in Islamic Cairo that’s overshadowed by the neighborhood’s famous towering mosques and minaret-topped mausoleums. Known as Sharia Khayamiya—the Street of the Tentmakers, or the Tentmakers Market—the alley is named for the art form’s original purpose: tent decoration. Like many forms of art, it’s taken different shapes over the years. Nowadays vibrant quilts and detailed cushion covers hang in the alley, bringing life and color to the market’s otherwise drab, deteriorating walls.

Some believe that khayamiya dates back as far as the pharaohs. But the business of selling it today looks different than it ever has before. And not just because these artisans—the last 20 left in the world—are surrounded by roaring mopeds and other marketeers on cell phones.

Tourism on the Street of the Tentmakers, as in much of Egypt, plummeted after the revolution in January 2011. As protestors swarmed downtown Cairo, embassies urged travelers to change their plans. The market, then bustling, grew quiet. Khayamiya’s primary target—tourists—stayed home. Those who braved a trip to Egypt skipped the chaotic, potentially hazardous maze of Old Cairo, opting instead for visits to the heavily guarded Great Sphinx or Great Pyramid of Giza.

For an art form like khayamiya, which has always relied on tourism, lack of foot traffic can sound like a death knell. Yet that’s only one of the challenges khayamiya faces today. Another is its perception as archaic, particularly among younger Egyptians. Many locals—including those who might have once taken up khayamiya themselves—see the traditional textile as outdated.

Séverine Evanno, who collects and sells khayamiya through her online store and Etsy shop, Couleurs du Nil, says kids today don’t want to follow in their fathers’ artisanal footsteps. “Young people are not patient enough to learn the job,” she says. “They prefer to drive taxis or Uber. They have no time to learn the stitchwork.”

Or any of the other things that go into making khayamiya. Artisans first sketch their design on paper, then poke tiny holes along the paper outline and use soot or powder to create a subtle stitching roadmap on the canvas. Once that’s in place they can begin laboriously hand-stitching each detail. It’s a process that takes hours, days—sometimes even weeks.

“The difficulty of crafting khayamiya is having patience, concentration, and skill,” says Al Farouk.

(And the ability to multitask. Khayamiya artisans, who work in the cramped back corners of their shops, also have to decorate their storefronts, market their work, and bargain with shoppers.)

Yet the result is something wholly unique—a fusion of color and artistic detailing unlike any other art form. Those intricacies are what drew Evanno to the Street of the Tentmakers in the first place. After one walk-through, she couldn’t get enough.

But after living in Cairo for six years, Evanno and her Egyptian husband moved to France, where she’s from. Evanno yearned for a way to stay connected to her second home. That’s when it hit her: khayamiya. By selling khayamiya in her online shop, she always has a reason to return to Cairo and the Street of the Tentmakers.

She’s since become a familiar and welcome face here—having an Egyptian husband and speaking the language helps too—who’s granted the rare opportunity to see the real khayamiya community in action. Behind the hand-stitched curtain, Evanno has found a mixture of kinship and competition.

“There’s a very special link between these artisans,” she says. “But they’re also competitive.” As business owners, khayamiya artisans tend to chase the selling trends, then innovate when there’s downtime. “If one of them starts to make a beautiful pattern and it becomes successful, the others won’t be happy, and they’ll start making the same one. That’s why you can go in every shop and see identical patterns.”

This approach can make it tough for individual khayamiya artisans to stand out. That’s where big smiles and sharp sales skills used to come into play. But with fewer tourists in the market these days, such opportunities have dwindled.

Beyond the internal rivalries bubbling within the khayamiya community, the remaining 20 artisans are also struggling with external competition. A new crop of khayamiya-style artwork—fabric replicas—is attracting local buyers who love the look of hand-stitched khayamiya but can’t afford the price. (A khayamiya quilt costs $200 or more, while two yards of replica fabric is $25.)

The khayamiya artisans consider these knockoffs a form of forgery. But Evanno—who also sells fabric replicas in her Etsy shop—thinks both versions play a role in preserving the tradition. “The khayamiya patchwork is like a painting, and the fabric is like a photo of the painting,” she says. “They’re not the same, and they’re not for the same use or the same population.”

Traditional hand-stitched khayamiya products are equal parts artwork and decor. The quilts, cushion covers, and wall hangings are not meant to be cut or tailored by the owner. For purists, that’s akin to ripping a painting in half.

So is treating the replicas like a true fabric. In recent years, some creative Egyptian buyers have begun adapting their cheap replicas into khayamiya clothing and curtains.

Some grumble that this approach is changing the traditional purpose of khayamiya as art. Evanno and others, however, argue that clothes and curtains are simply “changing the purpose to keep it relevant.”

Relevance is key to khayamiya’s survival. And nothing is as relevant today as the internet. Evanno’s digital storefront attracts shoppers from all over the world. But she’s hardly the only one selling khayamiya online. Traditional artisans now partner with Egyptian Etsy shop owners to reach customers where they are: on the web.

“Every shop owner has some partner working on selling khayamiya,” said Alshimaa Moustafa, who sells Al Farouk’s work in his Kufic Khayamiya Etsy shop. “Since they don’t have online shops [themselves], they sell their products wholesale, and the [online] shop owner markets and sells them in his own way.”

Time will tell if this ancient patchwork has found a digital salvation. But it’s the best hope for khayamiya’s survival. The fact that khayamiya is now available to anyone with an Internet connection and an Etsy account is what might ultimately save it from extinction.

Ironically, just as the khayamiya industry is adapting to the brave new world of online shopping, tourism in Egypt is starting to come back. Before the 2011 revolution the country counted as many as 14 million tourists a year. That figure dipped to 5 million in 2016. But in 2018, 11.3 million tourists visited Egypt, according to the global economic database CEIC.

Meaning the brick-and-mortar khayamiya shops may yet rebound. But only if travelers take the time to visit.

“People go to Egypt for sites like the pyramid[s] and the Sphinx,” says Evanno. “So many tour operators leave this area off their itinerary. You need to have tourists who ask to see something different, who ask to go off the beaten path.”

For those who do, the Street of the Tentmakers is waiting for them, right where it’s always been—alive with color, charisma, and khayamiya.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook