Fighting Whitewashed History With MIT’s Diversity Hackers

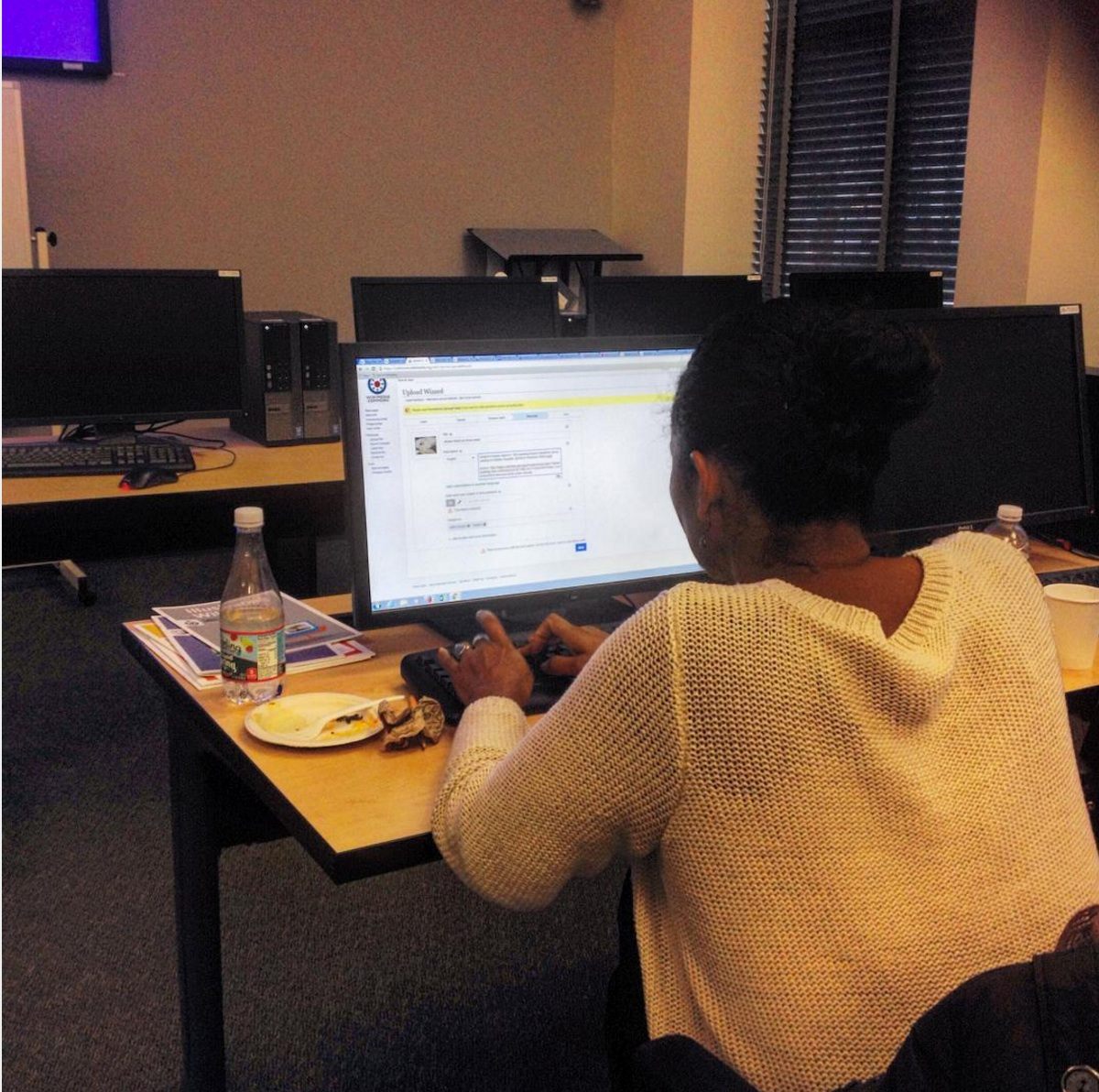

Hackathon participant Nelly Rosario, making the Wiki-world a more textured place. (Photo: Atlas Obscura)

It’s a scene no one would look twice at–on a Friday afternoon at the end of January, in a gray-walled MIT computer lab, a dozen wrinkle-browed hackers stare at their screens, surrounded by coffee cups and half-eaten cookies.

But this is no ordinary afternoon hack. The group is unusually diverse–old and young, male and female, from the Institute and the surrounding community. Most of them have books cracked open on their laps. And at the front of the room, on a whiteboard, is a list of subjects to tackle: not Python scripts or Javascript arrays, but “Marron William Fort” and “Margaret S. Collins.” For the next few hours, this group will lend their interdisciplinary talents to a surprisingly difficult task–editing black history into Wikipedia.

“Wikipedia’s goal is to share with the entire planet the sum of all human knowledge,” Phoebe Ayers, one of the hackathon’s organizers, tells the crowd as they set to work. “We’re not even close to that goal.” Ayers, a longtime Wikipedia editor who has cowritten a book on the subject, has just finished an extensive introduction of Wiki do’s and don’ts, arming the volunteers with the tools to make good edits and additions.

Around the room, the hackers choose their subjects, rifling through library books and going deep on Google searches. Tips fly from desk to desk: “obituary sections are full of interesting people,” or “look for Army photos, they’re all free to use.”

Hackers need snacks too. (Photo: Atlas Obscura)

Nelly Rosario, a writer and researcher for the Blacks at MIT History Project and a member of the Class of ‘94, is hoping to flesh out some existing pages. “Texture is so important to me,” she says. “I think sometimes we flatten history. If we know these people as human beings, we know the texture of their daily life, it becomes more real to us.”

Rosario has lately become fascinated by a 1920s celebrity couple, Myra Adele Logan and Charles Alston. “She was a surgeon at the Harlem Hospital, and he was a muralist–like the Diego Rivera of Harlem,” she says. “I’m trying to fill in some of her entry from details of his entry, which is way more in-depth than hers.”

Wikipedia’s skewed perspective is a well-known problem, acknowledged by the Wikimedia Foundation and much of the larger community, some of whom who have formed groups and campaigns to address it. What to do about it is much less clear. The issue is deeper than the site itself: as Ayers says, “there are a lot of inherent problems in how knowledge is represented,” throughout history and across media.

Since Wikipedia is a compendium of information that already exists elsewhere, it reflects this long-standing bias. In addition, Wikipedia’s editorship–the tens of millions of volunteers who add, tinker with, and argue about articles–is not particularly diverse.

“It’s largely younger, largely male, largely white,” Ayers says. “And people often write about their own interests, which is natural and makes sense. But what that means is that we have a lot of articles about software and famous military figures, and not a lot about, say, traditional women’s handicrafts or activists in the developing world.” For a site that aims to “really reflect the fullness of our collective human experience,” Ayers says, this is a big issue.

A Black History edit-a-thon in London in 2015. (Photo: Caroline Bressey/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

It’s “a nightmarishly vexed problem,” says Adam Hyland, a content expert at the Wiki Education Foundation, which works to bridge the gap between the site and academia. Hyland, who sports a black and green “Ask Me About Wikipedia” shirt, spends his afternoon jumping from computer to computer, helping people format sources and hashing out the finer points of the “Five Pillars,” the fundamental principles that underlay the whole Wikipedia endeavor. The last of these pillars is “Wikipedia has no rules,” a Fight Club-esque paradox that, though necessary to the spirit of the site, makes it difficult to exert change.

When new perspectives do manage to eke their way through, they’re subject to intense scrutiny. Groups of old-guard editors write scripts that show them edits from new users, and then police them overzealously, Hyland says, reversing their contributions and often scaring them off for good. The only thing that has “really moved the needle” is educational outreach–give a diverse group of people the tools, the desire, and the support to get through these obstacles, and the whole thing starts looking less monolithic.

Even at organized events, this is easier said than done. As the hackers dig in, roadblocks keep popping up–some common to all historical efforts, others unique to this one. One hacker, trying to separate a psychologist couple into two independent pages (“it’s like she’s glued to her husband’s side!”) has difficulty finding sources that credit the female half of the pair with anything. Another recalls making a prior effort, only to find her changes immediately reversed by the overzealous editors Hyland was talking about. Still another finds she can’t edit a page at all–it has been locked to new contributors after a different user repeatedly vandalized it.

Maya Wagoner dives into Dr. Dorothy Celeste Boulding Farabee’s page. (Photo: Atlas Obscura)

Maya Wagoner, a graduate student in comparative media studies, has been researching black history on her own since high school, and recently got involved in the Wikipedia scene. “So far it’s been terrifying,” she says. “It seems very easy to do, and then when you edit something, there is all this aggressive language–‘so and so patrolled your pages and took down your addition.’”

Wagoner is expanding the page for Dr. Dorothy Celeste Boulding Farabee, a 20th century obstetrician and civil rights activist, and has pages and pages of notes. “I’m afraid that even after I add a bunch to this, someone’s going to patrol it and take it down… as a new editor, all I’ve experienced is negativity,” she says.

Still, she says, “I’ll probably keep trying.” Rosario will too–in fact, she’s having trouble stopping. “I drove in from New York for this,” she says. “Now I understand why this is a four-hour session. I’m in a wormhole!” If she and her fellow hackers can keep their footing, that wormhole might start to look a little more like Earth.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook