England, But New: How John Smith’s 1616 Map Helped Define America

The name “New England” was like a colonial real estate ad.

In the mythology of the Americas, the English soldier John Smith is most famous for his association with Pocahontas, the Powhatan woman known for her interactions with Jamestown settlers. But he made another indelible contribution to what’s now the United States—he named the area of the country that stretches from Cape Cod up the coast of Maine. The region would later become a key part of the American narrative, the site of the first Thanksgiving. He called it “New England,” and the name stuck.

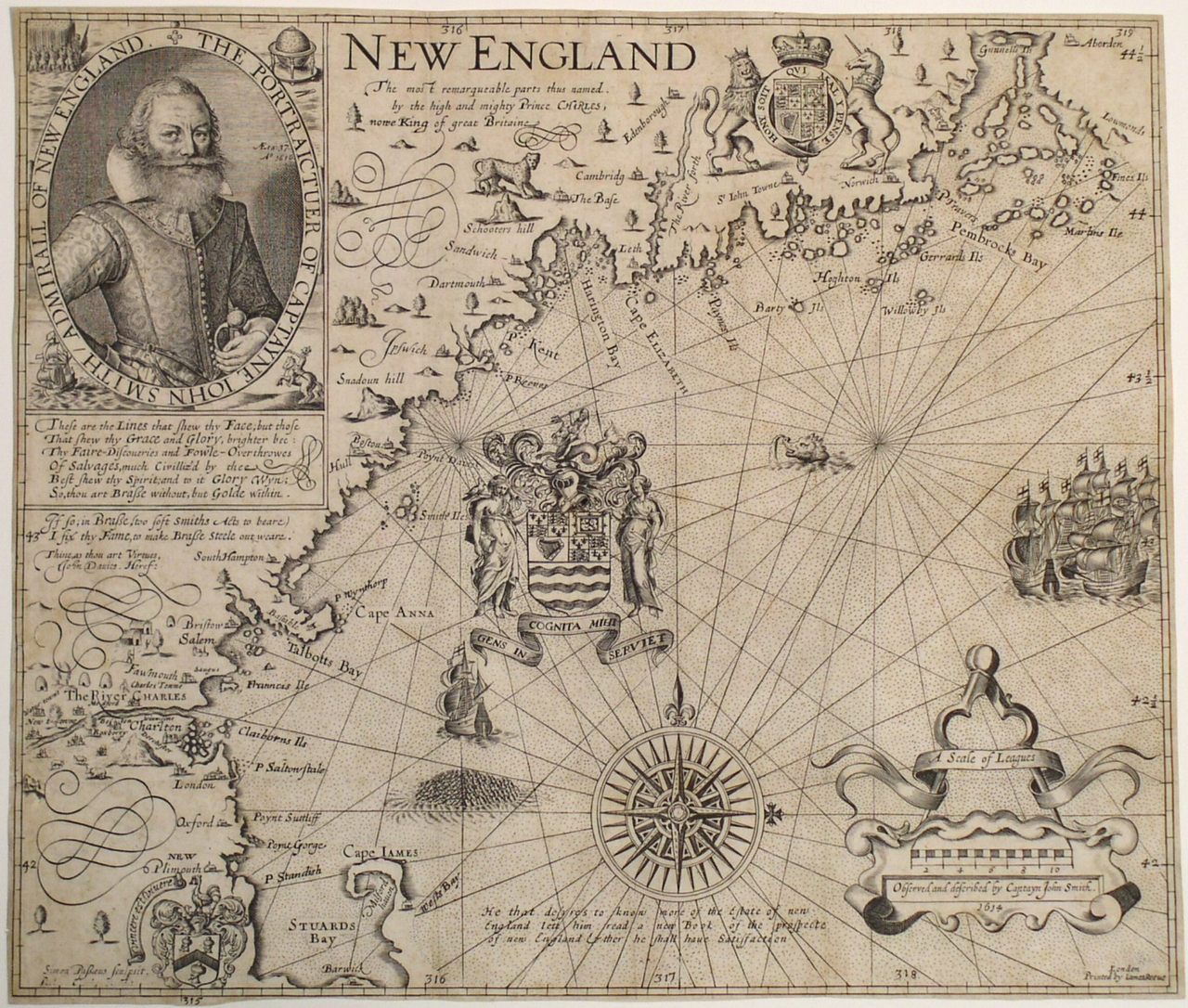

The map above, first published in 1616, marks the first time anyone called New England “New England.” Two years before, after being shut out of the leadership of Jamestown, and looking for a new foothold in the Americas, Smith joined an expedition that sailed up the coast of what was then called “North Virginia.” What he saw there sparked his colonial imagination. He could envision British settlements scattered along rivers, surviving on the rich fisheries, ample hunting, and potential farmland.

So Smith raised money to bring a party of settlers across the ocean, and in 1615 they set out, only to be quickly captured by pirates. After his release, Smith struggled to find further financing. When Pocahontas—who by then went by the name Rebecca Rolfe—planned a trip to London, Smith rushed to publish an account of his American experience, which included the New England map. “I would rather live here than anywhere,” he wrote.

It was an advertisement, a real estate brochure, of sorts. “The map conveys settlement as a sure bet,” writes historian Susan Schulten, in her book A History of America, in 100 Maps, published in fall 2018. But in 1616 the villages that dotted the map didn’t really exist. Smith let the then–Prince Charles (who would become king in 1626) swap in whatever he wanted for the indigenous names of places marked on the map. We still use a few of those names today—Cape Ann, the River Charles, Plymouth.

Before they set out across the Atlantic, the Pilgrims bought a copy of Smith’s map, although it’s unclear if they brought it with them, since they had intended to sail farther south. But they were blown to the area that Charles had called “Plimouth,” and they stayed there.

The New England that Smith imagined took form over the following decades, and in 1677 William Hubbard and John Foster published a homegrown map of the region (above). The settlers had just fought a war against the Wampanoag leader Metacomet (also known as King Philip), and the map is “the first that was ever here cut,” the creators note. It shows British settlements spreading through the Massachusetts Bay colony to the Connecticut River. It’s one of the only images left that New Englanders made in that era.

Smith’s map had left native tribes out altogether. The later map had to include them, as it was meant to show, in part, the conflicts settlers encountered. But Schulten points out that the native settlements are marked by trees, as if they’re part of the natural landscape. Whatever stories British settlers told about the “pristine” landscapes of “New England,” their maps reflected. To some extent, we still indulge in those myths today. The story of Thanksgiving, in its typical form, is about cooperation between settlers and the tribes who lived here already. But as these early maps indicate, colonists never saw the residents of this land as an important part of the story. They saw the land they wanted to make their own.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook