Found: A Rare Carved Stone That Could Rewrite Art History

A miniature masterpiece from the Greek tomb of the “Griffin Warrior.”

In spring 2016, a team of archeologists from the University of Cincinnati was digging at a Mycenaean site in the Pylos region of Greece when they made a surprising discovery: the intact tomb of a Bronze Age warrior dating to about 1500 B.C. The Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports declared the find the “most important to have been discovered in 65 years.”

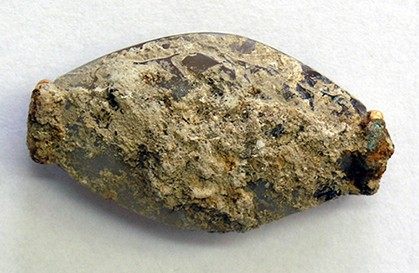

Now, almost two years later, the tomb has revealed its most valuable secret, and intricately carved sealstone that researchers are calling “one of the finest works of prehistoric Greek art ever discovered.” It didn’t look so at first, but once a thick crust of limestone was cleared off it revealed a detailed scene of a victorious warrior, one defeated opponent beneath his feet and another falling at the tip of his sword. And all this was carved in meticulous detail on a piece of stone just over 1.4 inches long.

The dig’s coleaders, married team Shari Stocker and Jack Davis of the University of Cincinnati, were surprised by the detailed engravings, including intricate weaponry ornamentation and jewelry decoration. Such work has never been seen before in art from the Aegean Bronze Age. “What is fascinating is that the representation of the human body is at a level of detail and musculature that one doesn’t find again until the classical period of Greek art 1,000 years later,” Davis explained in a release. “It’s a spectacular find.”

Indeed many of the details in the “Pylos Combat Agate,” as it has been dubbed for the type of rock it is carved on, become clear only when viewed with photomicroscopy, which has left the researchers wondering about the technique behind it. “Some of the details on this are only a half-millimeter big,” said Davis. “They’re incomprehensibly small.”

The “Griffin Warrior,” who was buried in the tomb and gets his name from an adorned ivory plaque buried with him, probably died around the time when the militaristic and austere Mycenaean culture, based in mainland Greece, conquered the culturally sophisticated Minoans, based on the large island of Crete, just south of Pylos. But much of what was found in the tomb appears to be of Minoan fabrication, which suggests greater and more complex cultural interchange between the civilizations than was previously known.

Stocker and Davis will present their findings in a paper to be published later this month in the journal Hesperia. According to Stocker, “This seal should be included in all forthcoming art history texts, and will change the way that prehistoric art is viewed.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook