Found: The Goofiest Crab That Ever Lived

It has the legs of a sea scorpion, the body of a lobster, and the eyes of an enormous larva.

Javier Luque’s soulmate isn’t just any other crab. Its legs aren’t slender and long like the gams on most crabs, but rather huge, flapping paddles. Its carapace, the hard upper shell of its body, isn’t round but elongated, rather like a lobster. Its eyes aren’t the typical crustacean pinpricks, but soft and glassy orbs so huge that they would be the equivalent of eyes the size of soccer balls on the average human. But still, Luque—who, it’s worth mentioning, is a human, and not a crustacean—loves this crab. “This animal came into my life without asking, like a lucky strike,” Luque says. “I know we were meant for each other.”

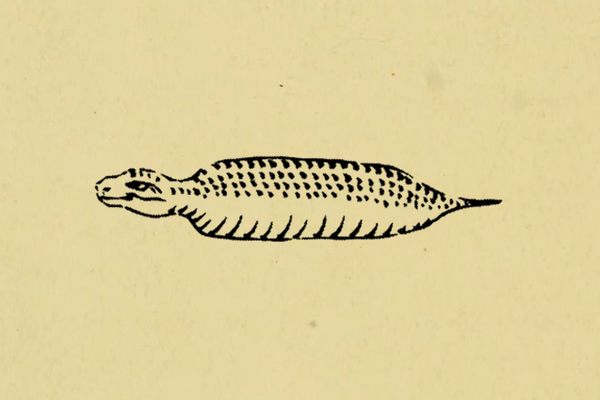

Luque, who works as a postdoctoral paleontologist in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Alberta and Yale University, named the newly described and very confusing crab Callichimaera perplexa, or “perplexing beautiful chimera,” in homage to its strange hodgepodge of features, according to a study published on April 24, 2019, in Science Advances. The name references the chimera of Greek mythology: a creature with a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and a snake’s tail. This odd crab is just as terrifying as its namesake, but on a smaller scale.

The chimeric fossil first entered Luque’s life in 2005, when he was an undergraduate student in geology. While hunting for fossils in Pesca, a town high in the Colombian Andes Mountains, Luque and a friend had stopped to catch their breath while walking back home after a long day in the field. As any budding geologist is wont to do, Luque hammered a nearby rock, which split to reveal a layer crammed with hundreds of crustaceans. As Luque looked closer, he recognized many fossils of comma shrimp and ammonites, as well as, he initially thought, some strange kind of spider, with eight flappy legs and huge bulky eyes. But as he peered closer, he saw the creature had pincers.

Luque proceeded to call several experts in fossilized crustaceans to see if anyone could identify his bizarre discovery. To his surprise, everyone else was just as stumped by the perfectly preserved specimen. “If you get to baffle the most knowledgeable experts on fossil crustaceans in the world, imagine how baffled I was!” Luque says. The creature transfixed him so deeply that Luque switched gears from dinosaurs and toward prehistoric crustaceans. Officially a crab—though technically a mystery—Callichimaera represents a novel branch in the modern crab’s ancestral tree, though its body parts bear an uncanny resemblance to animals from other groups. For this reason, Luque calls it “the platypus of the crab world.”

One of the quarter-sized crab’s most bizarre features are its mysteriously enormous eyes, which likely swiveled freely, too large to be contained by any eye socket. Luque finds them extremely cute. “We think the chimera might have had development similar to an axolotl, where it retained its baby features,” Luque says. “Which is why it looks like a pocket Pokémon.” He says these eyes suggest Callichimaera was a predator, as scavengers have little need for good vision. “If you had to have eyes that big, you would be using them actively,” he says. The crab might have dined on comma shrimp, which Luque calls “the noodles of the shrimp world.”

While most long-legged crabs crawled on the seafloor, Callichimaera swam. Its elongated body was much more hydrodynamic than a regular crab’s, and its oar-like legs helped it paddle through the water. “Most crabs in the world are crawly critters,” Luque says. “But this one was a dreamer! It dared to swim away into the water column, like a bird. Not many crabs do that.”

Beyond its evolutionary absurdity, Callichimaera has even greater significance as a fossil discovery made in the tropics. It’s quite understandable that very few researchers go to the tropics to find fossils, as the region has dense layers of vegetation and harsh weather that can make quick work of a fossil. But this lack of focus means researchers know very little about the prehistoric critters of those regions, according to Luque. “We are beginning to scratch the tip of an iceberg,” he says, adding that research institutions in the tropics often lack the budget and resources afforded to institutions in North America, Asia, and Australia.

For now, Luque will continue to investigate his goofy soulmate. He hopes to ascertain how the creature swam, what it ate, and, most importantly, how it saw the world. When Luque lies in bed at night, he often finds himself unable to sleep because he is too transfixed by the crab’s enormous, wobbly, and woefully unprotected eyes. “What were you using those eyes for!” Luque nearly shouts into the phone. “I must know.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook