Found: Vulgar Mosaics in a Roman Latrine

They offered bathroom-goers some raunchy entertainment.

It’s the year 200, you’re in southern Anatolia, and you’ve gotta go to the bathroom. If you happen upon the right latrine, you’re in for relief—of the comic kind.

Researchers from the Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project were surprised this summer to find crude, comic mosaics adorning one Roman latrine, satirizing figures from Greek and Roman mythology by depicting their nether regions. The vibrant, incidental find now lies carefully covered in Turkey, awaiting future study—but honestly, first glance kind of tells you everything you need to know.

One section of the mosaic depicts Narcissus, ostensibly admiring his own reflection like he does in the myth (just what he’s looking at is, unfortunately, obscured by dirt). But in this Anatolian take, Narcissus is admiring more than his face: In his left hand he proudly holds his penis, clearly impressed with himself and trying to impress us. But the artist won’t let him get away with it. Narcissus’ nose is exaggerated in the mosaic, contrary to the contemporary beauty standards he thinks he defines.

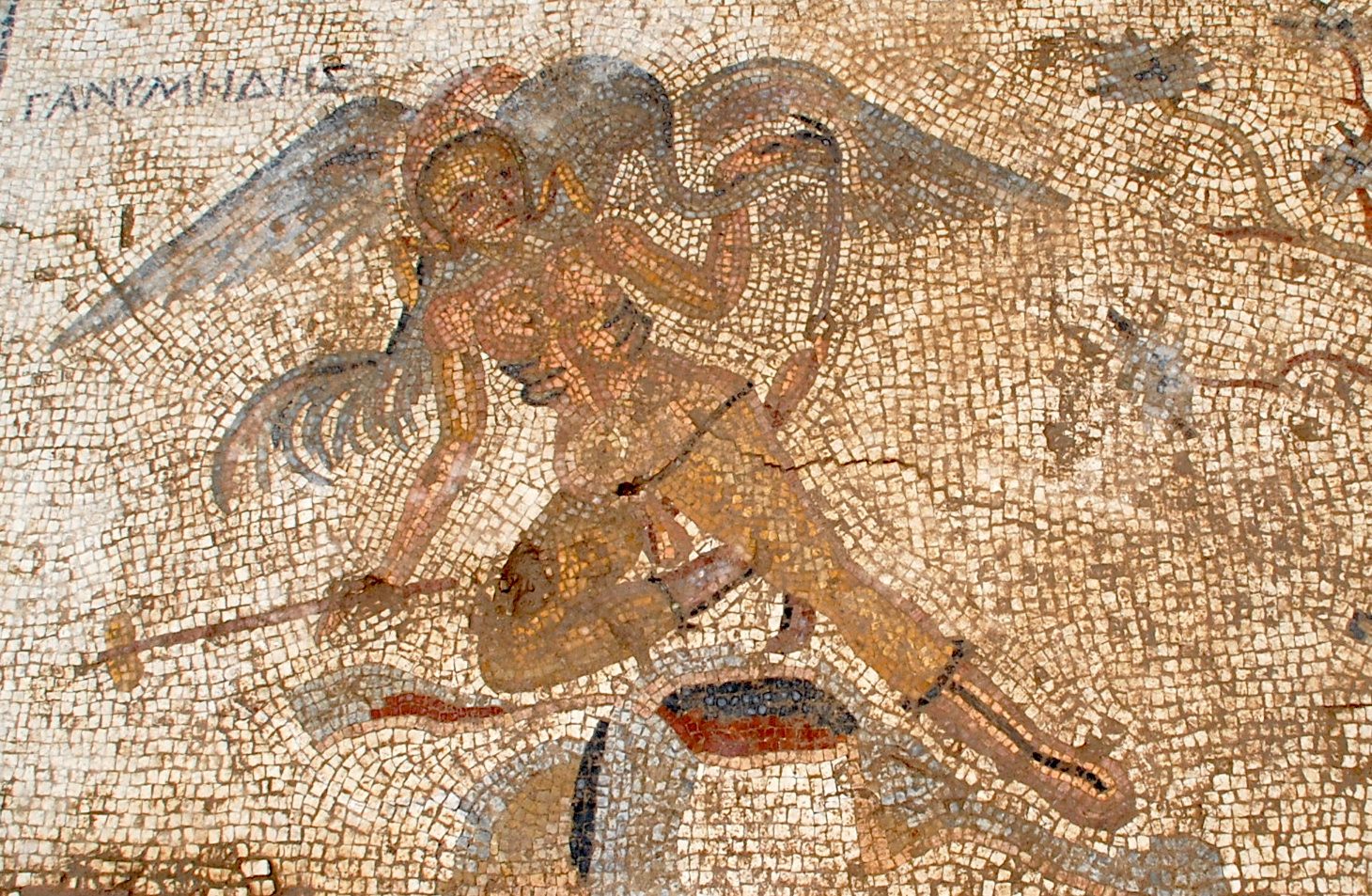

The other section is rather more subtle (and harder to discern), but just as bawdy. Some mythological context—supplied by the University of Nebraska’s Michael Hoff, one of the researchers—might help: Legend has it that Ganymede, another famously beautiful young man, was abducted by a smitten Zeus, who transformed into an eagle to swoop down to earth and carry the boy back to Olympus. To emphasize his boyish innocence, artists often depict Ganymede holding a hoop and a stick so he can enjoy some carefree hoop rolling, a common Greco-Roman game involving, well, spinning a hoop with a stick. Here, Ganymede is indeed holding a stick—but with a sponge at its end, so he can clean himself off like everyone else after using the facilities. It doesn’t seem like he needs it. Instead, an avian Zeus is cleaning Ganymede’s genitals—bent behind his back—with a sponge held in his beak.

Hoff rejects that the scene is meant to suggest sexual activity between Zeus and Ganymede. Instead, he says, it’s a sendup of iconic tropes that has few archaeological peers. (He estimates that the mosaic dates to the 2nd or 3rd century.) Excavated latrines rarely reveal hidden mosaics, says Hoff, let alone works with such risqué imagery. These artworks are the products of “pretty specialized labor” more befitting, say, a temple. So, depending on the results of future research at this and other sites, the effort expended on decorating the latrine could say a lot about Antiochia ad Cragum’s culture and priorities. Hoff, who has been researching the site for 13 years with the Research Project, says he became interested in the ancient city because it wasn’t a major, influential hub—“pretty small potatoes,” actually. It offers, he says, a sense of “what the regular people were like in Asia Minor.”

Rather irreverent, apparently.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook