Rotten Apples That Will Last Forever

A close-up look at the botanical glass artist Rudolf Blaschka’s last—and strangest—project.

To enter the Glass Flowers exhibit at the Harvard Museum of Natural History is to be immediately overwhelmed by perfection. The walls are lined with thousands of flawless plant examples, all rendered exquisitely in glass. The models, created by father-and-son team Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka beginning in 1886, were meant to help botanists study plant anatomy; as such, the room is full of bright stems, pert petals, and luscious fruits.

Currently, though, visitors have the chance to be tempted by a slightly different exhibit. In the mid-1920s, a few decades after his father’s death, Rudolf Blaschka began work on a series of diseased fruits, including about half a peck of sickly apples. After about 15 years in storage, these perfectly imperfect specimens—blackened, spotted, spore-ridden and spongey-looking—are back by popular demand, displayed in special cases in the middle of the exhibit space. “When they aren’t up, people look for them,” says collection manager Jennifer Brown. “They ask, ‘Where are the rotten apples?’”

As Donald Pfister, a professor of systemic botany at Harvard, explains, the models were originally meant as “an educational venture” in the then-burgeoning field of plant pathology. “It’s very modern to think about sustainability,” he says, “but back then, people were, too. They were always asking: What are the diseases and pests that might limit crop production?” In the absence of today’s tools—DNA analysis; color photography—the glass facsimiles “could answer the question, ‘What’s that blotchy thing?’”

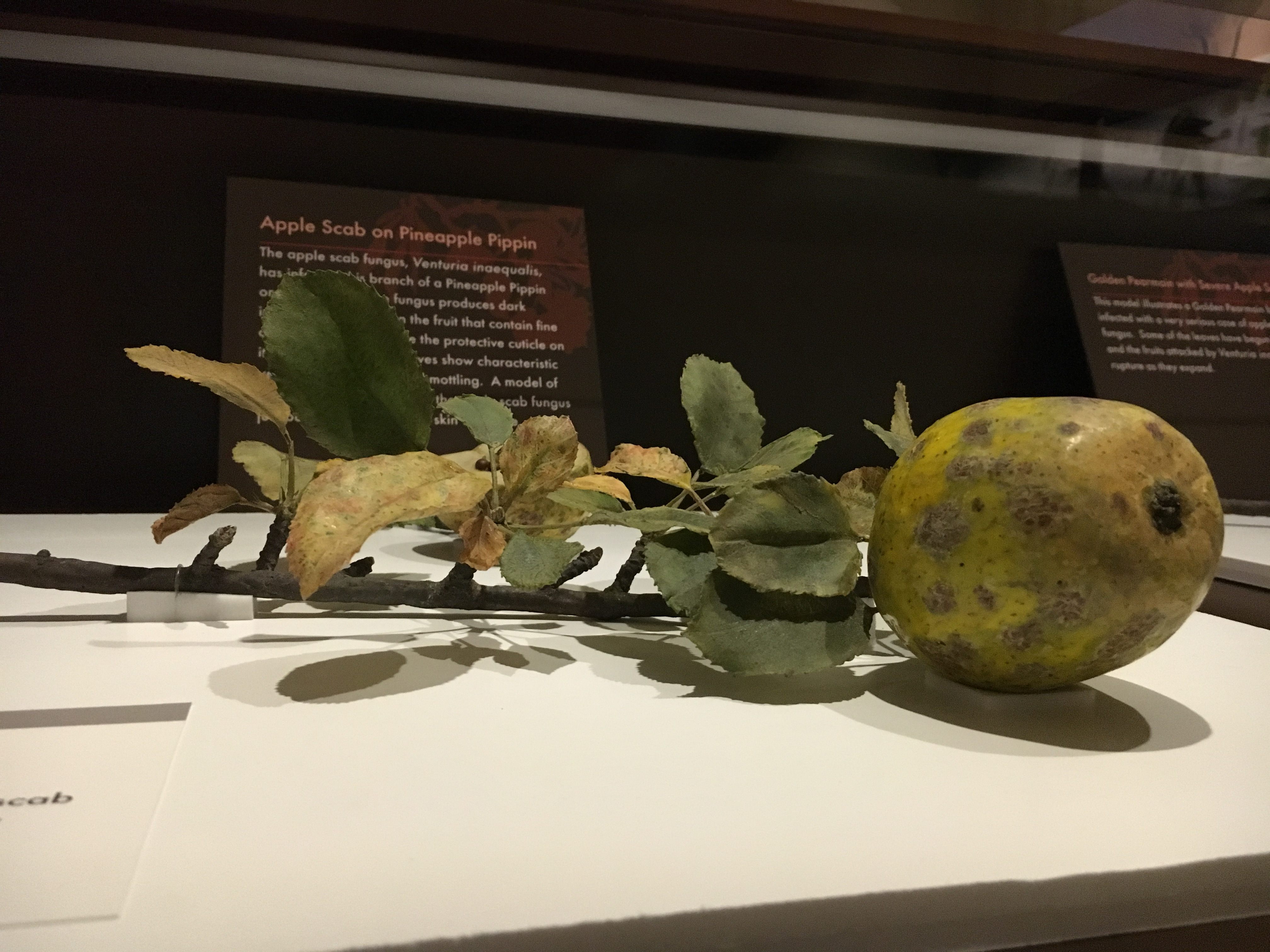

A survey of the blotchy things on view makes it clear that there are a lot of ways for an apple to go bad. Several of the glass fruits suffer from “apple scab,” an infection by the fungus Venturia inaequalis that yellows leaves and covers the fruit in small brown spots. Others have “water core,” from too much sun, or “apple scald,” which develops in storage. (The glass apples are coming off of about 15 years in storage themselves, and required some cleanup, as seen in this video.)

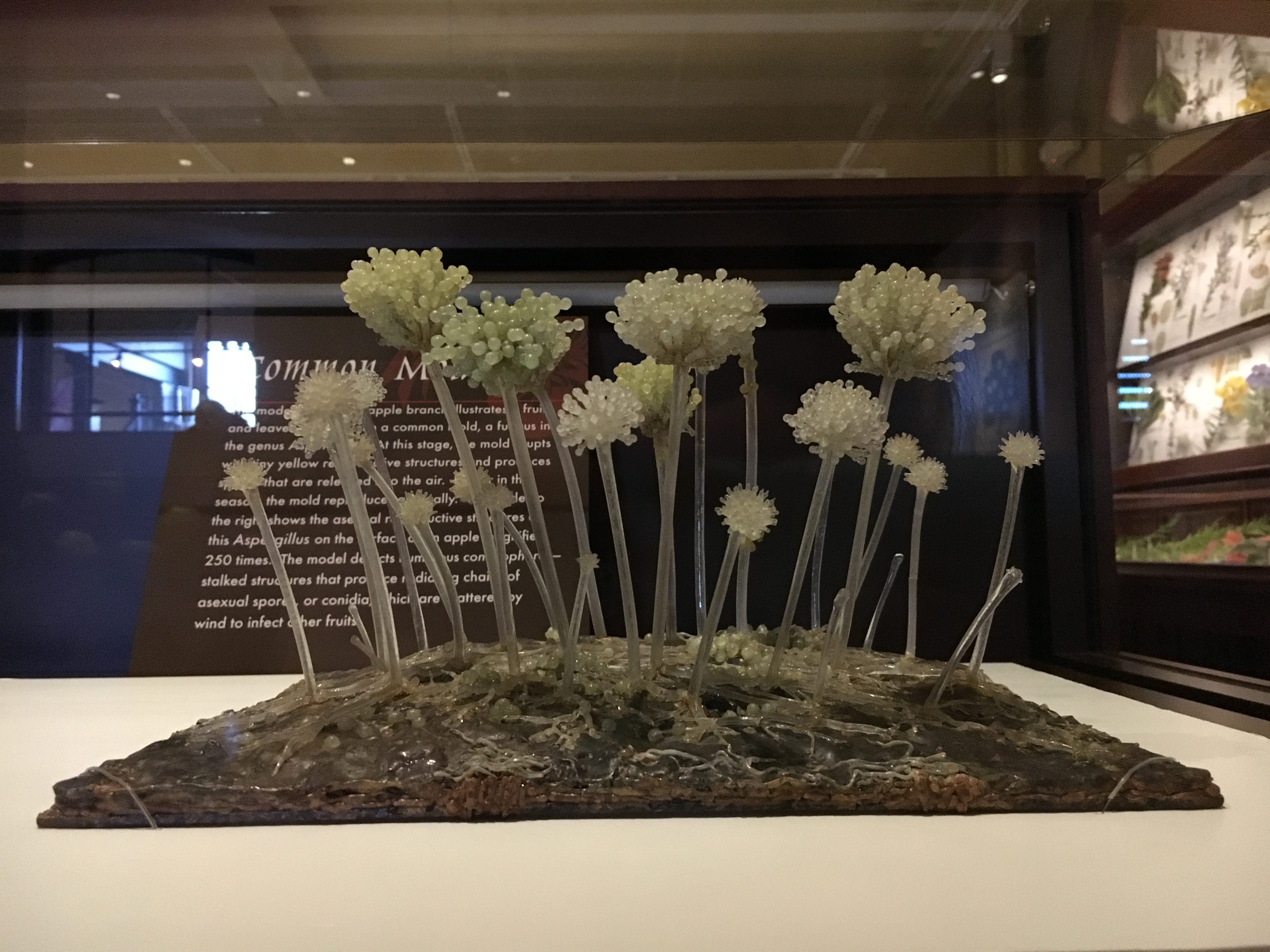

Many have brown rot, which means they’ve been “mummified” by another fungus, Monilinia fructigena, and turned into spore-producing machines. Because brown rot manifests in a variety of ways, Blaschka made a corresponding variety of apples, some covered in tumescences, others black and shriveled. He also made a blown-up patch of Aspergillus, another common infectious mold, which looks like a nightmarish, blob-ridden forest.

Blaschka lavished the same care on these diseased specimens as he did on his other, heartier models. Each crusty patch of apple skin is lovingly textured, every yellowed leaf perfectly shaped. “They’re the last body of work Rudolf worked on,” Brown says. He died just three years after he shipped them, in May of 1939, at the age of 81.

Most of the apples are about that age now. Unlike their creator—and the rest of us—they may well last forever, in a state of perpetual, beautiful decay.

“Rotten Apples: Botanical Models of Diversity and Disease” will be on display through September 2018.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook