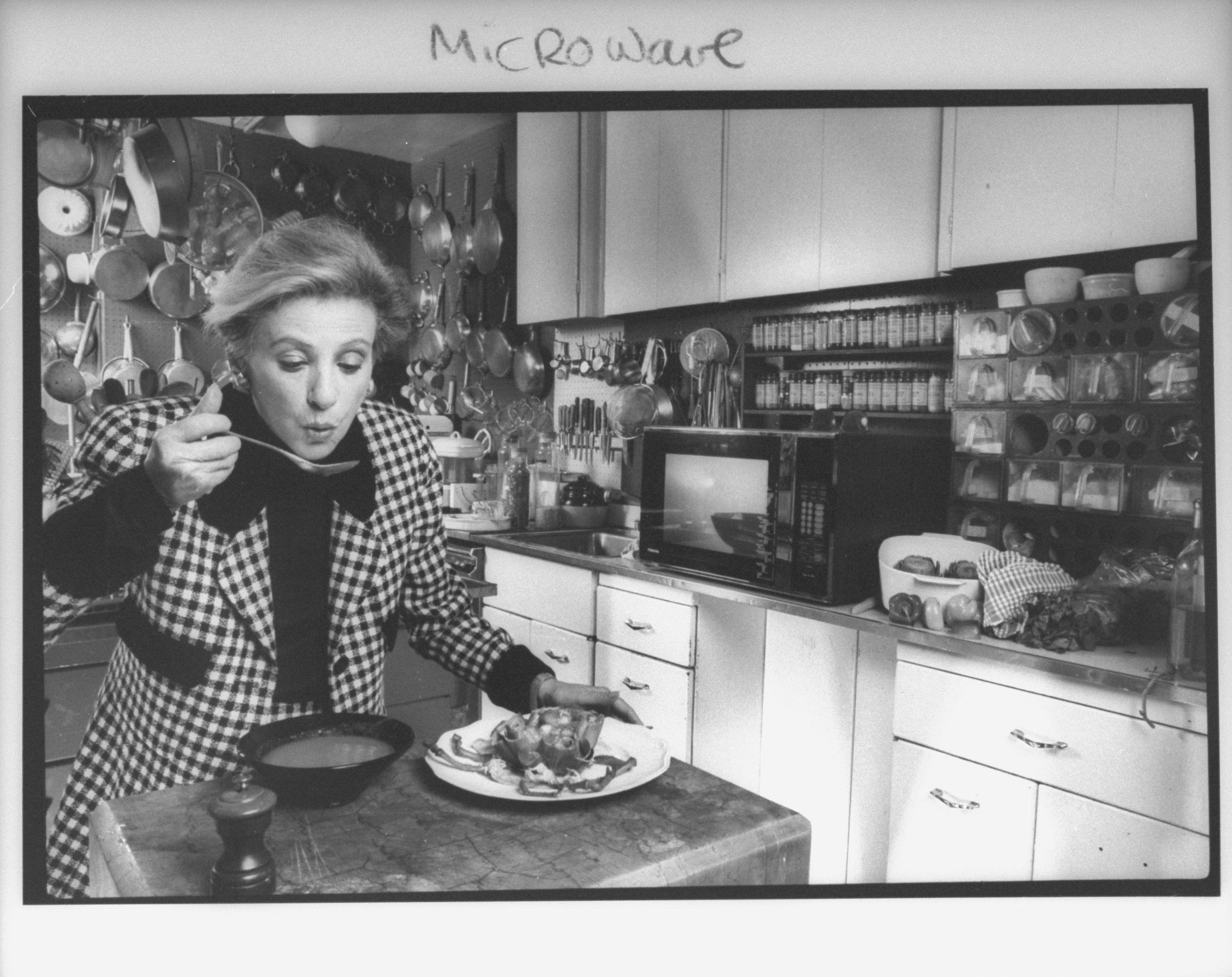

Remembering the Cookbook Author Who Made Microwave Meals Gourmet

Barbara Kafka bucked assumptions about kitchen appliances.

Earlier this month, Barbara Kafka—the contrarian cookbook author, chef, and former ballerina—passed away at her home in Manhattan. She was 84 years old. Her husband, Ernest Kafka, told The Washington Post that she’d wrestled with Parkinson’s disease, among other health complications. Kafka, who hailed from a well-to-do New York City family, was an accomplished cook who wrote about an unlikely kitchen tool—microwaves—and made seriously good food in them.

Kafka was born on August 6, 1933. Her mother was a labor attorney, and the first woman to litigate a Supreme Court Case, and her father was an executive with Parfums D’Orsay, a fragrance company. As a young woman, she often accompanied her father to dinner, which is how she got a taste of fine cuisine. She briefly danced in a company as a child and as a teenager, but suddenly stopped and rarely spoke about it. Later on, she edited copy for medical journals, which she once said was excellent cookbook training “because you have to be very exact or somebody’s going to die.”

She wrote many cookbooks, including one informed by her celiac disease and lactose intolerance known as The Intolerant Gourmet. Yet it was her 1987 cookbook, The Microwave Gourmet, that became her most well-known contribution to the culinary canon. At first, she admitted that she was a “microwave snob, as most of my chef and food-writing friends still are.” She turned a corner thanks to her daughter, Nicole, who let her know that she could heat water quickly in a microwave. Kafka made an artichoke, and was shocked at how good it was.

“The microwave oven makes it possible for all of us to cook and eat good homemade food again,” she wrote in the book’s introduction. In characteristic, straightforward style, she added: “If the microwave oven cooks something badly, I will be the first to tell you; but you will find that it cooks some things better than any other kind of cooking.” In particular, Kafka swore by the microwave to cook time-consuming fare such as risotto. “I feel I must defend making risotto in the microwave oven as so many of my readers have done this,” she once wrote to fellow cookbook author Mark Bittman. “There is really not a lot of stirring. I don’t know about your shoulders, but mine are grateful.”

As someone who had bucked the conventions of her upbringing, Kafka was no stranger to bold statements. She spoke of the microwave as vital to enhancing certain foods and flavors. “Once you have tried microwave-cooking fish, you may never cook it any other way unless you grill it outdoors,” she wrote, much to the chagrin of office workers everywhere. She swore that you get “addicted” to the speed of a microwave. The Microwave Gourmet’s hundreds of thousands of readers could likely attest to that.

She also stirred up culinary controversies by advocating against conventional wisdom: Namely, that a microwave could act as a deep-fat fryer, and that ovens could be heated to 500 degrees to roast poultry, vegetables, and meat. But Kafka was not someone who was easily dissuaded, even though Julia Child and James Beard balked at her techniques (despite her long friendship and collaborations with Beard). “Tell Barbara Kafka that a recipe wouldn’t work or a combination was against the rules, and when you looked up she wouldn’t be there—she’d be in the kitchen,” the food journalist Corby Kummer told The New York Times.

Kafka is remembered as a prolific writer and a celebrated cook, one who was honored with a James Beard Lifetime Achievement Award in 2007. But more than anything, she was immensely curious, had a knack for challenging conventions, and was a voracious reader. “I don’t believe in reinventing the wheel,” she once said. “There are cultures that are not mine. And in order to learn about them, I read.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook