Hell on Earth: Five Experiences of Eternal Damnation before Death

Devoured by a monstrous worm or boiled nude in a vat of searing pus — what sort of extraordinary agonies await you sinners in the afterlife? Mythological and religious concepts of death and the afterlife are loaded with convolution, ambiguity, and speculation. Many cultures embrace a trial of judgment after death, whereupon their souls are either salvaged or pitched into eternal damnation. Here we will look at five representations of hell, and what transpires during that final judgment.

Chinese Mythology: Diyu

Fengdu Ghost City, which was built to represent Diyu (photograph by Robin/Flickr)

Fengdu Ghost City, which was built to represent Diyu (photograph by Robin/Flickr)

In Chinese mythology the concept of Diyu, or “earth prison,” meshes the combined afterlife variants of Confucianism, Taoism, folk tales, and the Buddhist hell realm of Naraka. Diyu serves as a temporary zone in which the dead are brutally smited until their tenderized souls are ready for reincarnation. Originally consisting of over 90,000 hells, various interpretations have reduced the number to ten courts or 18 levels, each dealing with a different atonement.

King Yama, wrathful ruler of Diyu, oversees the punishment of all the dead and administers a formidable yet temporary, atonement that directly correlates to the severity of their sins. Perpetrators may be sawed in half, trampled and penetrated by a horned beast, deep fried in a wok, or be forced to climb mountains barbed with knives.

For mortals who want to get a taste of Diyu before their judgment day comes, they may visit Fengdu, the Chinese “ghost city” modeled after the nether world and its daunting trials.

Torture in the afterlife in Fengdu City (photograph by GS3/Wikimedia)

Woman being put in a cauldron of blood & skulls in Fengdu Ghost City (photograph by GS3/Wikimedia)

Man being sawed in half in Fengdu Ghost City (photograph by GS3/Wikimedia)

Man being sawed in half in Fengdu Ghost City (photograph by GS3/Wikimedia)

Norse Paganism: Niflheim

Nidhogg at the Wodan Timbur Coaster (photograph by Jérémy Jännick)

Nidhogg at the Wodan Timbur Coaster (photograph by Jérémy Jännick)

As one of the Nine Worlds of Norse mythology, Hel, or Helheim, is the kingdom of souls for the common civilian who did not earn his death through battle. Eponymously named for this underworld, Hel was also the guardian of the realm, a hulking beast of a woman with a half-blackened face of corpse-like beauty. In the 13th century, Poetic Edda and Icelandic poet Snorri Sturlson’s Prose Edda, suggest that Hel and its even icier netherworld Niflheim (“World of Fog”) were places of the blackest, bitterest, frigid dread.

In the depths of Niflheim, the lowest roots of Yggdrasil, the World Tree, stretch down for nourishment from Hvergelmir, a boiling cauldron of a well. Nidhogg (meaning “malice striker,” or “striker in the dark”), a 30-foot, carrion-obsessed worm gnaws on the roots of the tree while she waits for delectable corpses of perjurers, adulterers, and murderers to wash up on Dead Man’s Shore. Before Christian influence brought focus to individualized punishment for one’s moral standing, the pagan concept envisioned a neutral destination of rot and renewal. Like worms in a compost bin, the messengers of death in the Norse underworld act to encourage rebirth. Old branches die off so that new ones grow stronger. As is true for the Earth itself, the living can only flourish with the existence of decay.

To experience Niflheim while you’re still mortal, take a ride on the Wodan Timbur Coaster, a massive wooden coaster at the Europa-Park theme park in Rust, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany. Passengers queue up inside the nine enchanting worlds of Norse mythology, including the chilling, primordial, frost cave of Niflheim, where the scornful Hel herself reigns supreme.

Wodan Timbur Coaster (photograph by Jérémy Jännick)

Wodan Timbur Coaster (photograph by Jérémy Jännick)

Wodan Timbur Coaster (photograph by Jérémy Jännick)

Wodan Timbur Coaster (photograph by Jérémy Jännick)

Mayan Xibalba

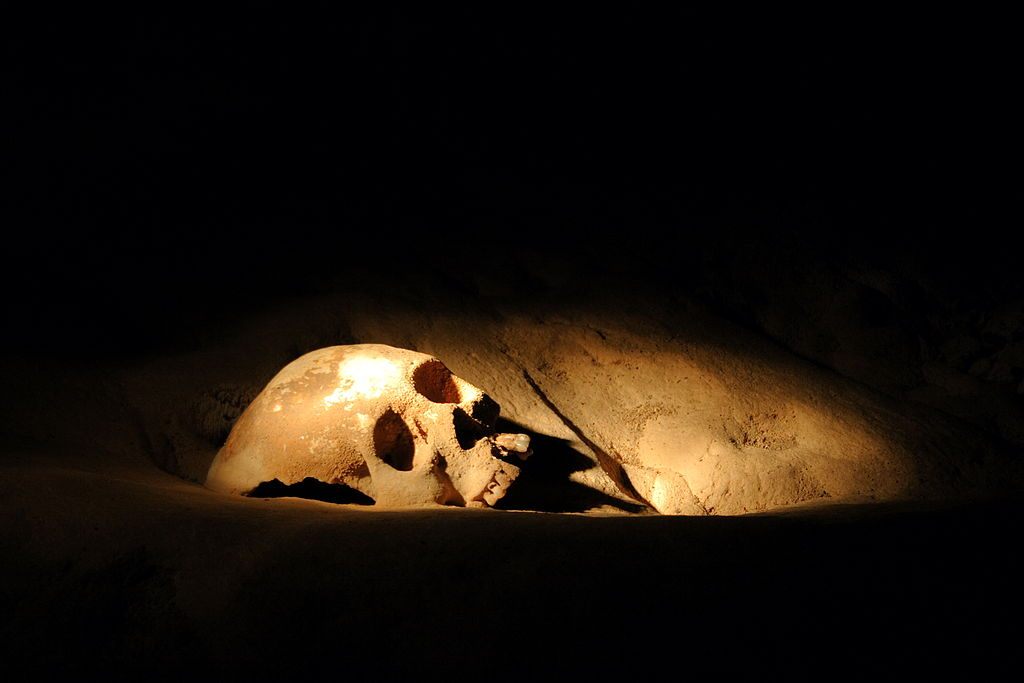

Skull in Actun Tunichil Muknal, Belize (photograph by Antti T. Nissinen/Wikimedia)

Skull in Actun Tunichil Muknal, Belize (photograph by Antti T. Nissinen/Wikimedia)

According to Mayan mythological texts, including the seminal Popol Vuh, the Mayan underworld Xibalba, translated as “a place of fear,” is an underworld ruled by 12 lords. Hell-bent on human suffering, the Lords of Xibalba, with names like Pus Master and Bloody Claws, wield their weapons of fear, pain, and starvation in various houses full of treacherous obstacles, from rivers full of blood, pus, and venomous insects, to trials of personal humiliation.

In the 16th century, the physical entrance to Xibalba was believed to be the Candelaria Caves in Cobán, Guatemala. Actun Tunichil Muknal (Cave of the Crystal Sepulchre), a cave structure in the Tapir Mountain Nature Reserve of Belize, is also believed to be the passageway to Xibalba. Access to the cave requires a laborious trek with extensive hiking, underwater swimming, and hours of wading through a cold river. Inside the cave, vaulted ceilings display dripping outcrops of stalactites between bored holes of nesting bats.

Skeletal remains from ritual sacrifices and ceremonial ceramics containing “kill holes” to release the spirits of the deceased line the cave floor. The most famous skeleton in residence is the “Crystal Maiden,” the calcified remains of a teenager who may have been sacrificed to a Mayan god nearly 1,000 years ago.

The “Crystal Maiden” in Actun Tunichil Muknal (photograph by Peter Andersen/Wikimedia)

The “Crystal Maiden” in Actun Tunichil Muknal (photograph by Peter Andersen/Wikimedia)

Persian Zoroastrianism: House of Lies

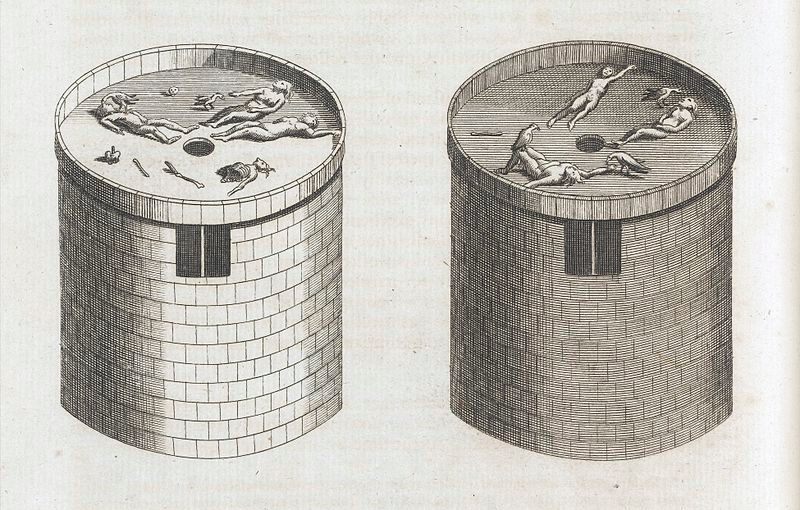

Drawing of the Zoroastrian “Towers of Silence,” where bodies are picked by the vultures (via Wellcome Images)

Drawing of the Zoroastrian “Towers of Silence,” where bodies are picked by the vultures (via Wellcome Images)

The ancient Persian religion of Zoroastrianism once reigned over the land that is now Iran. Still followed today by 2.5 million, the Zoroastrian belief is that your soul will be judged harshly upon death. Traditionally, this sect believed that a dead body was unclean and susceptible to demon contamination. Bodies were positioned within the concentric rings atop a Dakhma, or Tower of Silence, where they were washed by the elements, picked clean by vultures, and then tucked into the ossuary to decompose until the remaining substances flowed into the sea.

But what becomes of their souls? After a person dies their soul is believed to suffer some separation anxiety, so it lingers for a few days before its final judgment at the Chinvat Bridge. There stands a woman who reflects the soul of the dead person. If she appears as a beauty, the person is sent to the House of Song for heavenly exaltation. If she is a wretched hag, the wicked soul is cast into the House of Lies, where a dark and fetid wasteland awaits with punishments that fit the crimes.

Inhabited by demons, she-beasts, witches, and noxious animals, Ahriman’s underground kingdom provides unspeakable torture, pain, grief, and a palpable stench you can cut with a knife. Each soul endures their punishment utterly alone, sustaining themselves on a continuous force-fed diet of festering fluids and venomous reptiles.

Yazd Towers of Silence (photograph by Taranis-iuppiter/Wikimedia)

Yazd Towers of Silence (photograph by Taranis-iuppiter/Wikimedia)

Ancient Egyptian Religion: Duat

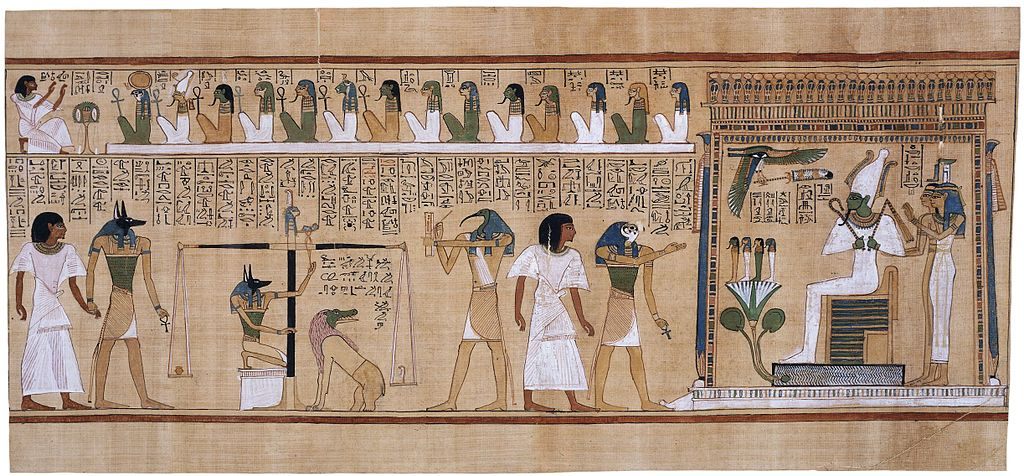

Weighing of the heart in the judgement of Osiris, from the Book of the Dead (via British Museum)

Weighing of the heart in the judgement of Osiris, from the Book of the Dead (via British Museum)

Picture it: Egypt, 2000 BCE. Osiris was dominating as far as deities go, and for a few hundred years he remained the undisputed ruler of the underworld, Duat. He was the only deity to earn the coveted “god” title. Egyptian religion had pragmatic and intuitive motivation, as they favored moral balance over total piety. As with many other religions that reinforce a balanced life, the Egyptian vision of hell functioned as a place to end one life and begin another. The ancient Egyptian concept of hell may have influenced the Christian, Islamic, and Judaic versions.

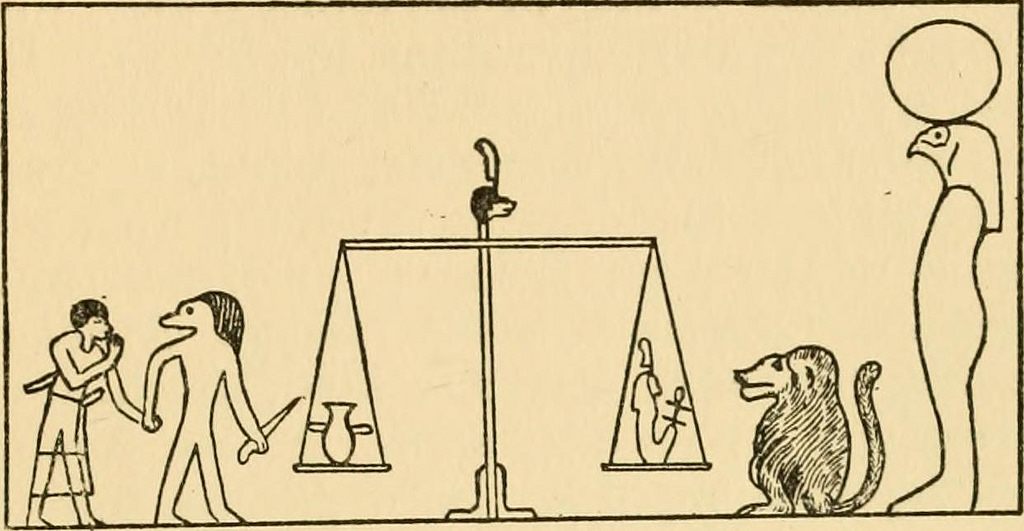

The deceased could give a “Negative Confession,” where they bring attention to all the horrible deeds they did not commit, such as causing pain to the multitude, purloining the cakes of the gods, catching fish with bait of their own bodies, and other shameful acts that repulsed the deities. In the Books of the Netherworld — ancient Egyptian funerary texts inscribed on walls and objects — spells and rituals illustrate instructions for the dead. In the final judgment called “The Weighing of the Heart,” the heart of the deceased is weighed in the scale of Ma’at, goddess of truth, balanced with a single feather. If a man’s good deeds outweigh the evil, his heart will balance with the feather.

One offense too many and he is ravaged by Ammit, “Devourer of the Dead,” a phantasmic gluttonous amalgam of crocodile, lion, and hippopotamus parts. The process is vividly illustrated in the Book of the Dead, which survives in scraps of papyrus in museums around the world, and etched on tombs.

Weighing the Heart, from “Osiris and the Egyptian resurrection” (1911) (via Internet Archive Book Images)

Weighing the Heart, from “Osiris and the Egyptian resurrection” (1911) (via Internet Archive Book Images)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook