Exploring the Haphazard Archive of a Paris Film Legend

Henri Langlois rescued thousands of rare reels, but was “famously bad” at caring for them.

In 2014, an archivist at the Paris-based Cinémathèque Française opened a box labeled “Sherlock Holmes.” Inside, she found three different films. One of them turned out to be a long-lost treasure: a late 19th-century American silent film starring an actor named William Gilette, who also played Holmes on stage over three decades. Posters for the film had endured and made it something of a legend among Sherlock devotees, but no copies were thought to have survived.

The Cinematheque restored the footage in partnership with the San Francisco Silent Film Festival and it was released on DVD the following year.

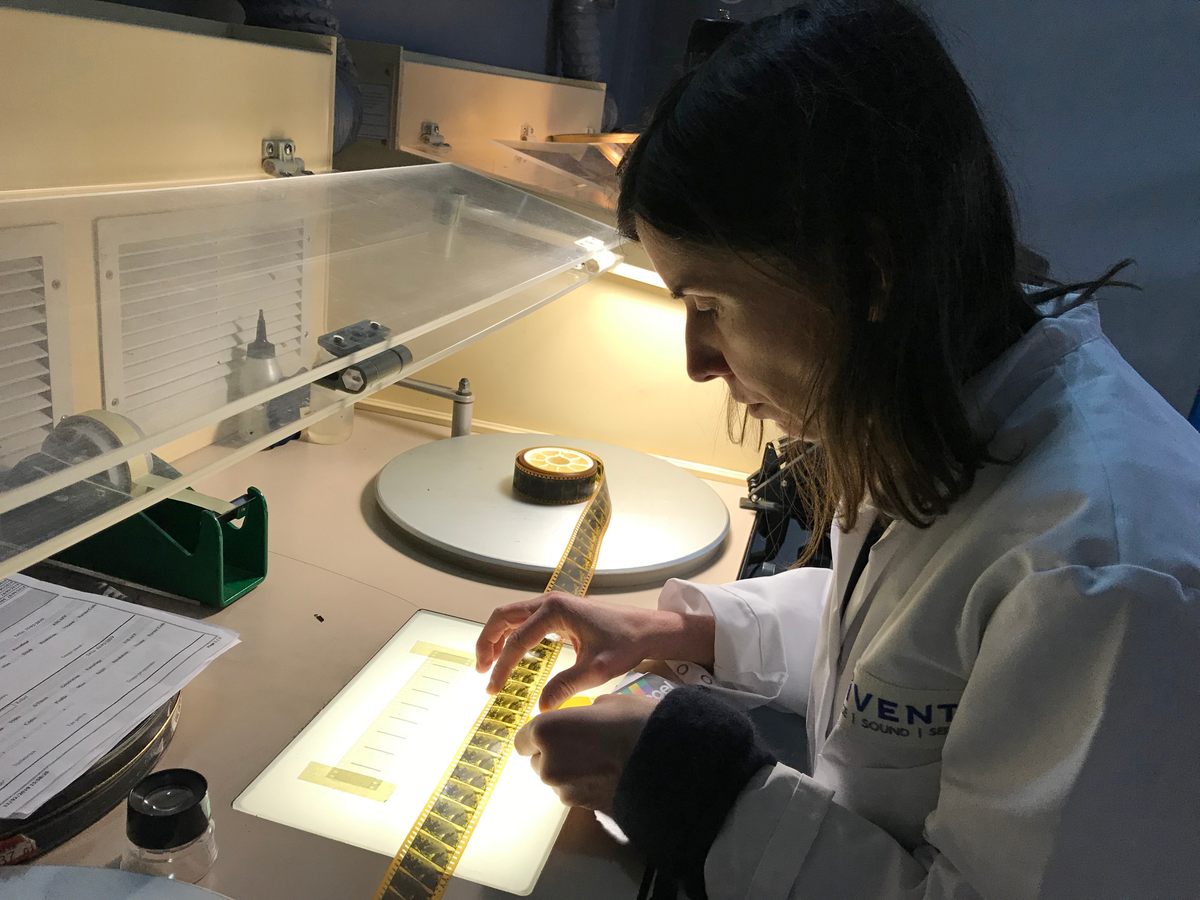

Discoveries like these have been happening since staff of the Cinémathèque began the process of re-cataloguing its collection in 1992. Because aging film can warp and crumple over time, especially in less-than-ideal preservation conditions, staff open every box and film canister, confirm what’s inside, and note its state of preservation.

“I think we’ll finish perhaps in 10 years,” said lead conservator Céline Ruivo in June of 2019, a full 27 years after the project began.

The Cinémathèque Française, the now-massive audiovisual archive, began under the bed of a very young French film enthusiast named Henry Langlois.

In the mid-1930s, as talking pictures grew more popular, Langlois began acquiring—you could say rescuing—silent films.

Even in these films’ heyday, reels were often dumped unceremoniously after their runs in theaters. With little commercial value, reels of silent films were melted down wholesale for their raw ingredients and to become consumer products, from combs to nail polish.

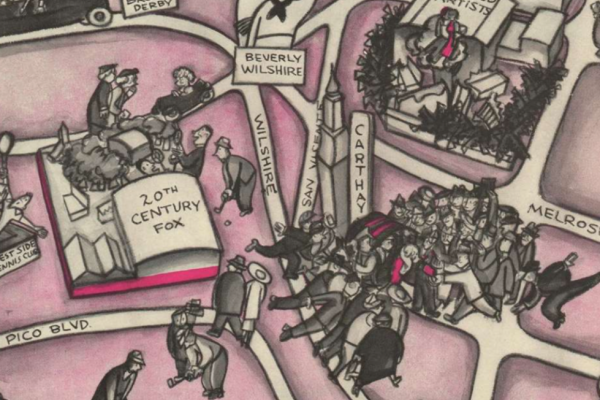

By the time young Langlois acquired his first film (the German silent horror flick The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), nearly all of Paris’s 200-plus movie theaters had been outfitted for sound, according to film historian Eric Smoodin. The destruction of silent films accelerated, to Langlois and other silent film buffs’ dismay.

Fledgling cinema preservation movements emerged in parallel in several European countries, the United States and Australia. Significant early archives were formed by MoMA in the United States, and the British Film Institute (BFI) in the United Kingdom.

In France, Langlois and friends took on this less-than-glamorous work, rescuing reels of film from recycling facilities, financially strapped distribution houses, and even flea markets. Stacks of the extremely flammable nitrate-based film stock eventually filled his parents’ apartment. With Georges Franju, Langlois founded La Cinémathèque Française in 1936, to continue saving films and, equally importantly, continue screening them.

“He used to say films have to breathe, so if you don’t project them regularly, they will die,” says Jan Christopher Horak, former director of the UCLA Film & Television Archive. But by running the film through a projector “without checking if there was a negative or a backup print of a film … you were putting them at a significant danger.”

During the German Occupation of World War II, Langloise continued his preservation efforts opportunistically, taking funding from the collaborationist Vichy government while also subverting German censorship.

The Vichy granted the Cinémathèque administrative space in a building shared with the General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs, which oversaw the implementation of the Vichy regime’s anti-Semitic policies. Langlois used his relationships to protect and grow his collection. When an SS officer asked for a military history film, Langlois bartered with him for the original negative of the 1930 film, The Blue Angel, starring Marlene Dietrich.

The Germans had an outright ban on British and American films by 1942, as well as a list of French films considered to have subversive anti-German messaging. Langlois set out to conceal films the Germans wanted destroyed and smuggle others overseas. At his request, Langlois’ allies hid film canisters in their homes and gardens. His colleague, Jewish-German emigre and film historian Lotte Eisner, spent time in hiding with a cache of films, including Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, in the dungeons of a chateau in the Unoccupied Zone of southern France.

In Paris, Langlois also organized secret showings of Soviet and American movies the Germans had outlawed, including at the Cinémathèque’s theater housed in a museum called the Musee de l’Homme.

Jean Rouch, then an engineering student, wrote that “In this empty Paris of the German occupation, in 1940-41, the Musee de l’Homme was the only open door to the rest of the world.” Rouch would later become a filmmaker.

“All this contributed to the mythological status of the Cinémathèque,” says Ruivo. After the war, Langlois held marathon film screenings. Attendees included directors who would go on to create French New Wave cinema, including Jean-Luc Godard, director of Breathless, and François Truffaut, creator of The 400 Blows.

Langlois had “incredible influence [on the] post-war generation of filmmakers,” says Horak, “who literally took their seats for weeks at a time in the Cinémathèque Française, watching film after film after film.”

Langlois became a larger-than-life figure, eclipsing his international peers and collaborators, such as Franju and Eisner. Described as rail-thin in his youth and elephant-like in his old age, Langlois chain-smoked and seemed to work incessantly. He appeared frequently in the media as a charismatic and often disheveled visionary.

In a 1971 profile of Langlois in LIFE Magazine, Rudolph Chelminski wrote of the collector’s “omnivorous appetite.”

“He collects everything, absolutely everything. If someone offered him a training film on brick-laying he would accept it with thanks and stick it off somewhere in one of the innumerable subterranean vaults that hold his treasures like so many bottles of vintage Bordeaux,” Chelminski marveled.

Langlois came to see film as a part of the historical record, and discouraged predictions for what would turn out to be of value.

“Judging, like criticism is a game,” Langlois told Chelminski. “It is gambling with the future. So, I take all films.”

“He didn’t define cinema as simply narrative fiction + documentary + avant-garde/experimental,” Rick Prelinger wrote of Langlois in an email.

The founder of the Prelinger archives of commercial, educational and other extra-canonical historical films held that Langlois “collected widely and without prejudice, and in so doing enabled expanded senses of viewing, research and appreciation that would last long beyond his own life.”

“[Langlois] is without a doubt,” says Horak, “the most famous film archivist on the planet.”

However, the scale of Langlois’ ambitions for the Cinémathèque were often at odds with his characteristic, improvisational style. With few resources, Langlois pinballed between carrying out restorations himself, organizing viewings, and creating a museum of cinema artifacts.

For decades, the Cinémathèquee had no comprehensive film catalogue. Many fragile reels were stored in conditions that hastened their decay. In 1959, 5,000 films nitrate left outside on a hot July day under a glass canopy awaiting transport caught fire and were completely destroyed.

“His methods are sort of famously bad,” says Smoodin. Langlois “was not really a modern archivist because his practices were so ad hoc and haphazard.”

“Procedures were not adequately respected,” acknowledges the Cinémathèque’s present-day conservator, Ruivo, “but mostly because of a lack of means.”

In 1968, the Cinémathèque’s board, with the support of French culture minister André Malraux, who had clashed with Langlois over the disorganization of the archives, removed him from the top of the institution. Street protests drew New Wave directors including Truffaut and Godard, finally leading to Langlois’ reinstatement. He received an Academy Award for his efforts on behalf of cinema just a few years before his death in 1977.

“There is a great deal of nostalgia for the Cinémathèque as it was in the ’50s and ’60s” under Langlois, says Smoodin. “Malraux is still seen as the bad guy in all this even though it’s understood Langlois’ methods are terrible.”

Today though, at least organizationally, says Ruivo, the “Cinémathèque of Langlois is no more.”

After losses sustained in another fire in 1997, the government invested in rehabilitating the institution. Its library, museum, and screening rooms moved to a Frank Gehry-designed building in eastern Paris.

The organization now holds more than 44,000 films, not to mention documents and ephemera, costumes, and a sizable collection of vintage cameras. For now, tens of thousands of films reside in the stone Fort de Saint-Cyr outside Paris; others made from early and unstable cellulose nitrate stock share space with the younger Centre National du Cinéma (CNC) archive. Planning is underway for a new facility that will unite the entire archive.

Ruivo now manages a team of archivists. As cataloguing moves forward, they can only speculate about whether a film discovered in a box with a completely different title was mislabeled by an overtaxed Langlois or deliberately hidden from the occupying Germans.

Entire lost films turn up maybe once or twice a year. More often, conservators discover salvageable fragments, which can be recombined with pieces held in other archives to recreate a damaged work.

“The really positive and beautiful side of the archives is rediscovery,” says Ruivo. “When we rediscover titles we’re also changing the history of cinema in a certain way, which is often written as a function of the films that were accessible at the time.”

Langlois’ legacy is also undergoing a process of revision, says Horak. The Cinémathèque holds its own institutional archives, which upon review seem to reveal a larger role for Lotte Eisner—the Jewish employee who hid with the banned films in the French chateau during the war—in organizing the acquisitions that allowed the Cinematheque to continue to grow.

“She worked for the Cinémathèque Française for decades,” Horak says, “even though she never got credit for anything.”

Horak fondly evokes a famous line from the 1962 Western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance to sum up Langlois’ legacy. It is originally delivered by a newspaperman about the movie’s villain, played by John Wayne.

“If you had a choice between printing the truth and the legend,” Horak loosely quotes the reporter, “print the legend.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook