A Rooster, a Duck, and a Sheep Walk Into a Hot Air Balloon…

…and make aviation history, of course!

In the year 2018, we tend to take human flight largely for granted. But in the early days of aviation, even sending up a large balloon seemed like a potentially deadly bit of hubris. So when the first passenger-ready hot air balloons began taking to the skies, their designers decided to test them out with some animals first.

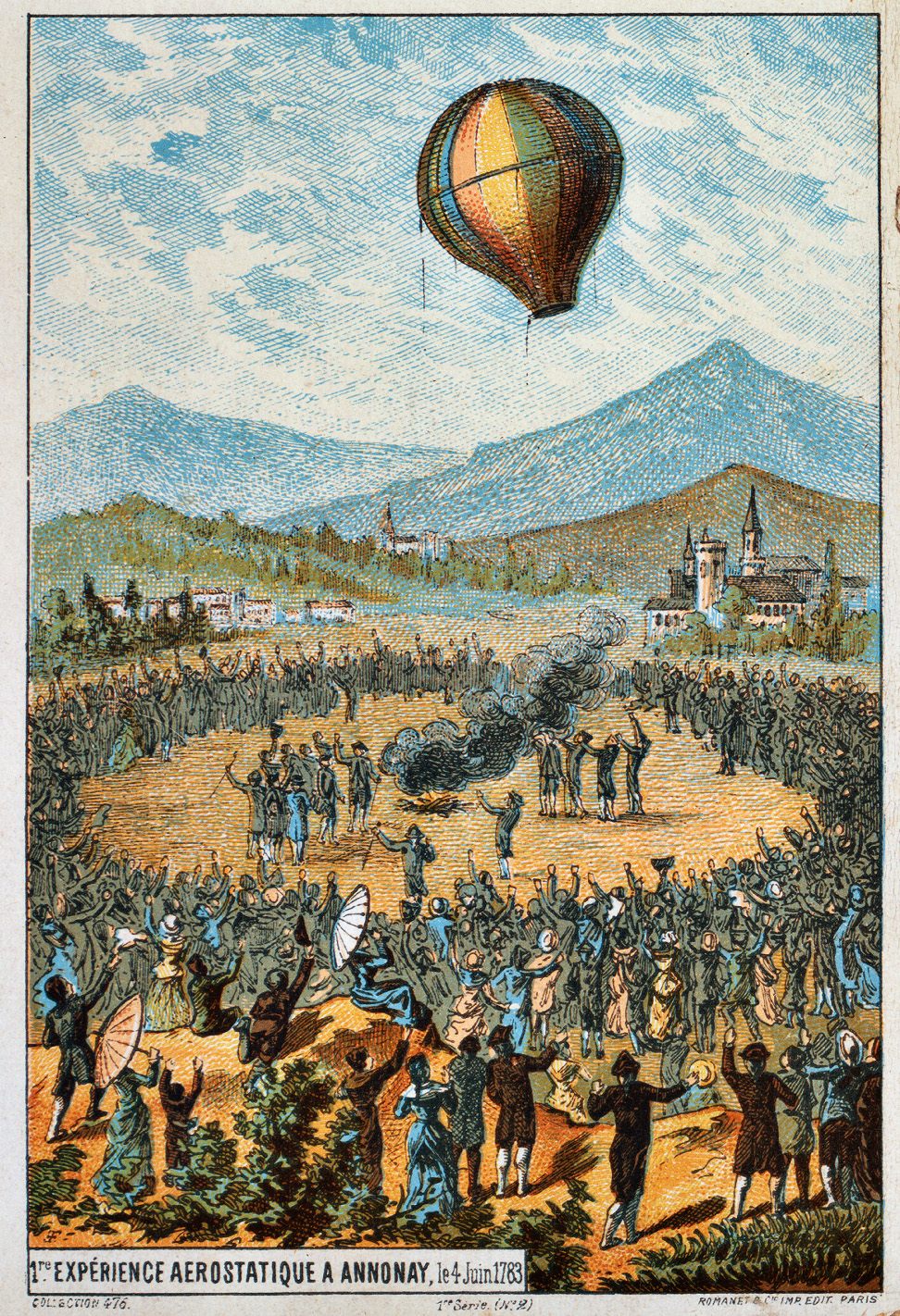

Even though it would be a rooster, a duck, and a sheep that would first brave the air in a balloon, we have the brothers Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier to thank for it. The Montgolfier brothers pioneered the hot air balloon as we know it (which is to say, a large balloon that floats under the power of heated air, as opposed to a lighter-than-air gas such as helium) in the late 1700s. They were just two of 16 children born to their family in a region of south-central France, which at the time was known for its paper-making. As adults, the two brothers became well-known paper manufacturers, but an interest in invention eventually led their lives in a different direction.

It’s unclear where exactly the Montgolfier brothers got the idea to tinker with hot air balloons (the basic technology had been around for ages in China), although the story tends to be that one of the brothers noticed some laundry rising up over a fire as it dried. Whatever the impetus, they first began experimenting with small-scale versions of their eventual creation. They built boxes made of lightweight wood, which they covered in thin taffeta fabric and then filled with hot, smoky air. The experiments worked, even if they didn’t totally understand why at first (at one point they even speculated that smoke contained a rare, lighter-than-air component they dubbed “Montgolfier Gas”). After a series of successful scale tests in 1782, it was time to try the real thing.

On September 19, 1783, the Montgolfier brothers set up an exhibition of their new flying balloon at Versailles, which would, for the first time, carry living creatures. Over a year or more of testing, their balloon had evolved to resemble the bulbous shape we’re familiar with today, and they knew from previous public tests in their hometown that it would fly. What they didn’t know was what altitude might do to a living thing.

In addition to the thousands of people who gathered to watch the flight, the Versailles demonstration had been organized for the benefit of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. To best test the effects of altitude, the King suggested that the brothers send up a couple of convicts, but the Montgolfiers instead went with a trio of animals. They selected one sheep, one duck, and one rooster to brave the unknown heights. According to Introduction to Aerospace Engineering With a Flight Test Perspective, an aviation textbook, the sheep (named, Montauciel, French for “Climb to the Sky”) was chosen for its similarities to human physiology; the duck, clearly already able to fly at high altitudes, would act as a control; and the rooster, a bird that never gets very high off the ground, would act as a comparative case for the duck.

The animals were placed in a cage suspended beneath the now-iconic blue-and-gold balloon, and they were set aloft. As described in an account contained in the 1983 book The Montgolfier Brothers and the Invention of Aviation 1783-1784, the balloon was heavily buffeted by wind as it was being inflated, but eventually lifted off, sailing uncontrollably for about eight minutes before landing in a wooded area some two miles away.

When the animals were finally recovered they appeared virtually unharmed from the trip (not accounting for psychological damage). As recalled in a 1921 Aviation Review from the U.S. Navy, the only injuries suffered were from the sheep kicking the rooster.

The Montgolfier brothers would go on to perform a series of successful hot air balloon flights with humans aboard, and the rest is aviation history. But we all owe a debt to that trio of creatures who not only spared some inmates from a bit of human experimentation, but also gave us the confidence to keep on flying.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook