How The World Looked When Jesus Was Born, According to Roman Geographers

It was a far different world when these maps were made.

Two thousand years ago, around the time that Jesus of Nazareth was born, the second Holy Temple was still standing in Jerusalem. The Great Pyramid at Giza was already 2,500 years old, but the Library of Alexandria was still around. In Rome, the Colosseum hadn’t been built yet.

It’s a bit uncanny to think about the political geography of a time and place that’s also the setting for a timeless story—the birth of Jesus Christ. Because that story is so often told, its context feels familiar. And, in the part of the world that Jesus lived in, the best knowledge about the rest of the world was in some ways thorough and accurate. But there were profound differences, too: most importantly, the Mediterranean Sea was still a geographer’s main point of reference, if not the center of the world.

Today, the best scholarly guide to the world Jesus was born into is a man called Strabo. He was born in Amasia, a town in the central north of what’s now Turkey. One of the great works of his life was a 17-volume geography, which described in detail the contours, cities, and cultures of the world as it was known to the scholars of his time.

Amasia was on the edge of the Roman empire, and when Strabo was born around 64 B.C., the province in which he lived had only been annexed a couple of years before. But he was part of an elite family and was brought up in the Greek academic tradition, which, like the Great Books curricula of today, was a little obsessed with Homer (who was considered both a poet and, Strabo wrote, “the founder of the science of geography”).

Strabo would have learned rhetoric, grammar, and philosophy, the most commonly taught subjects of the time; read Aristotle; and studied mathematics. Maybe it was living on the fringes of the empire that made him such an eager traveler. He spent a few years in Egypt, traveled south to Ethiopia, west to Italy, and as far east as Armenia. This, he boasted, made him the most widely traveled geographer of his time.

An artist’s image of Strabo, whose work was popular in the Age of Exploration (Image: Public domain/Wikimedia)

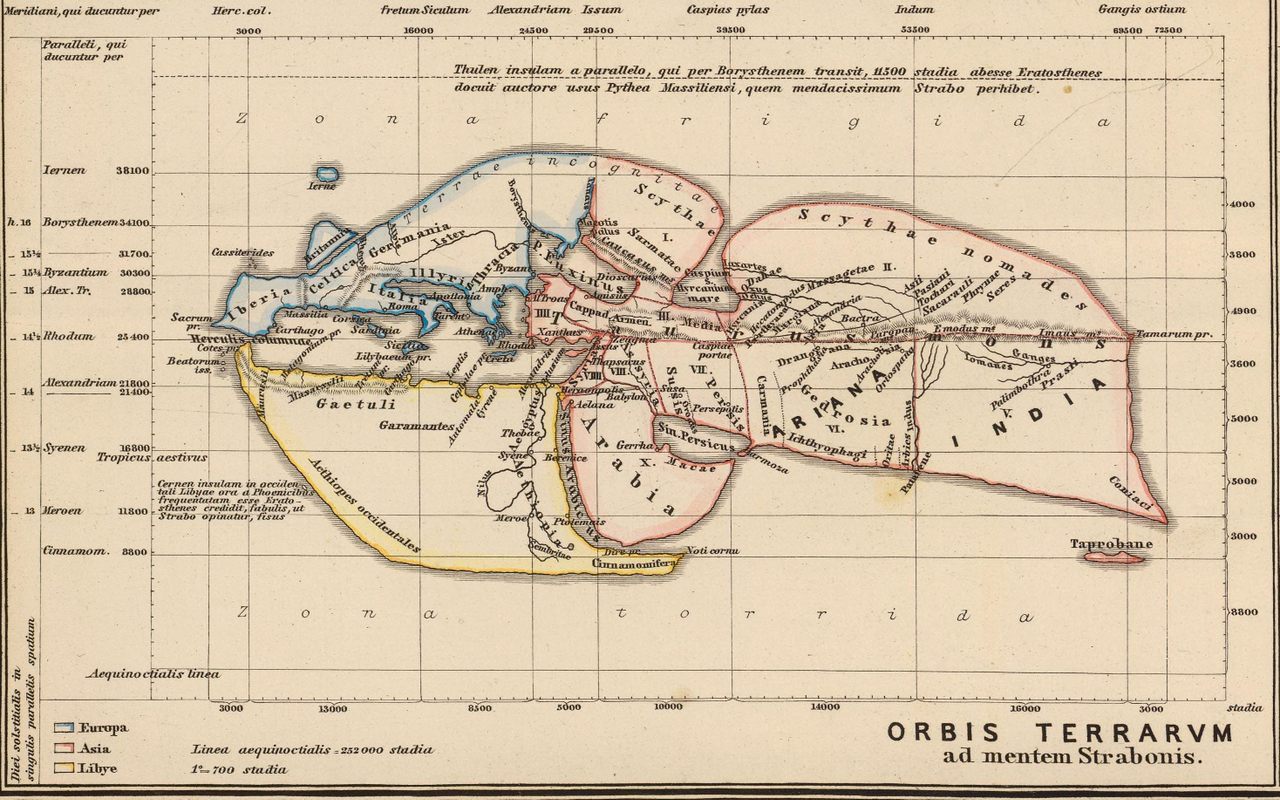

Here is what the world looked like to Strabo and his contemporaries: the globe was divided into five sections, with two cold bands on either end, two temperate bands, and one hot and “torrid” band at the very center. The inhabited world, a large island, was confined to a northern quarter of the globe and was surrounded by oceans. Or at least, that’s what was assumed: no one had ever circumnavigated the known world.

To the south of the Mediterranean sea was a continent sometimes called Libya; to the east was Asia; to the north was Europe. Geographers of the time knew that India was to the far east, Ethiopia to the far south, Iberia to the west, and “Scythia” and “Celtica” to the north. (Neither very clearly corresponds to any country we have today.) Britain was already known, and Mediterranean scholars had an idea that Scandinavia existed, but not its extent.

The largest missing piece of their knowledge, besides the continents of North and South America, was China. In 2 A.D., a census of the Han dynasty showed that its people numbered around 57.5 million. The Roman Empire, which had around 45 million people in it at the time, seemed to have little idea that China existed.

Besides his own travels, Strabo mostly relied on the accounts of sailors, who traveled the water by keeping coastlines in sight; his information about India came from historians of Alexander the Great’s campaign, which had reached India about 300 years before.

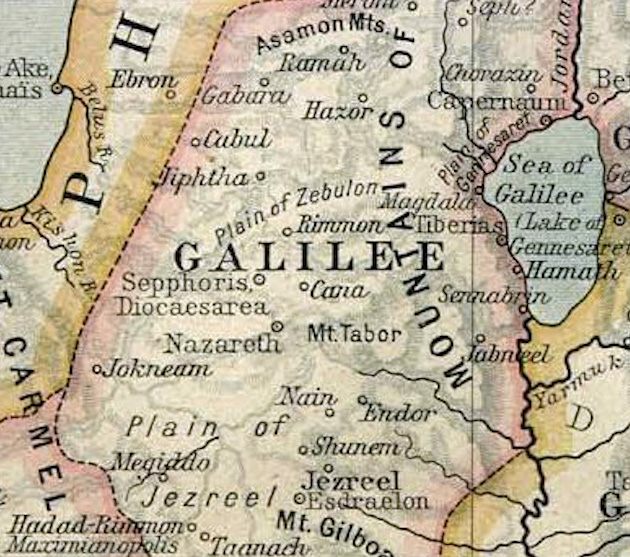

Ancient Galilee (Image: Public domain/Wikimedia)

In this world, the land between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River, modern-day Israel and Palestine, barely rated. This area was not particularly rich or accomplished, but in the Greek and Roman view of the world, it was strategically situated, providing an overland passage to Egypt.

Strabo’s account also includes some history of the Jewish people. He explains how “an Egyptian priest named Moses” led a group of followers who believed that God is “one thing which encompasses us all” to the place where Jerusalem now stood. Strabo continues:

He easily obtained possession of it, as the spot was not such as to excite jealousy, nor for which there could be any fierce contention; for it is rocky, and, although well supplied with water, it is surrounded by a barren and waterless territory.

Not long before Jesus was born, this area was governed by King Herod the Great, whom Rome had appointed as the ruler of all Jewish people. After his death, his three sons were willed parts of his kingdom, but they did a terrible job; one died in exile in what’s now southern France (which was considered a punishment back then).

Since then, the order of this part of the world had “degenerated,” Strabo wrote. There was a brief period of relative peace during the time that Jesus lived; around 6 A.D., the area that Herod had governed was moved more directly under Roman control, though not as a full province. (One of Herod’s sons still ruled the area of Galilee where Nazareth was located.)

But the calm wouldn’t last long. In 70 A.D., there was a revolt against Roman control, and the Second Temple was destroyed. Essentially, Jesus of Nazareth lived in an unstable place, far from any center of power–just the sort of place where people might be particularly interested in a new religious vision for how to navigate the turmoil of the world.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook