How to Find a Meteorite

It’s a long shot—but if you’re keen to look, here’s how to start.

From Earth, space can seem vague and distant—endless specks of light, a planet or star or far-off galaxy, mostly static unless you’re watching for a while. Maybe that’s why shooting stars—dynamic, fleeting, and fast—capture the imagination. They remind us that in the vastness of space, things are whizzing around. And these things sometimes come to visit us on Earth.

NASA estimates that some 48.5 tons of natural extraterrestrial material, such as dust or small chunks of asteroids, rain down toward our planet each day. Before these space rocks reach our atmosphere, they’re called meteoroids. When they enter our atmosphere, they become meteors—and many burn up, with that telltale shooting trail across the sky. When objects survive to fall to Earth, they’re known as meteorites. Sometimes, with smart sleuthing and a lot of luck, they can be found.

But that’s a long shot: The Meteoritical Society records only 1,824 confirmed meteorites found in the United States between 1807 and July 10, 2019. If you want to go for it, though, here’s how you can raise your odds.

Know where and how to look.

There are at least two factors to consider when deciding where to focus your search: where meteorites fall, and where you’re most likely to be able to spot them amidst other rocks, plants, and visual background noise.

Meteorites have been dropping from the sky for ages, and have landed all over the place, but to start, it might help to follow the trail of fairly recent falls. Marc Fries, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, has compiled a list of ways to keep tabs on meteorites by consulting weather radar for their distinctive reflectivity and velocity, among other characteristics.

This might give you a rough sense of where fragments landed—very rough. And even if you suspect that the space rock might still be there, undisturbed by construction or anything else—some sites are bound to be frustrating. How are you supposed to pick out what is likely to be an extraordinary small, brownish rock under vegetation, or in a sea of countless others that look a lot like it?

That’s what David (Duck) Mittlefehldt, another planetary scientist at NASA Johnson Space Center, found when he traveled to southern Israel in pursuit of meteorites and came back empty-handed. Meteorites are often dark, and the desert he scoured is freckled with dark-colored rocks with more local origins. “The meteorites, if they were there, would not have stood out like the beacons that you see when you’re in Antarctica, scooting across the bare ice,” he explained on the Johnson Space Center’s podcast, “Houston We Have a Podcast,” in January 2018. In Antarctica, on the other hand, he added, “you can find a black rock a couple of centimeters across from a great distance,” because it pops against the snow or pale blue ice. The same is true in paler-hued deserts such as Chile’s Atacama. More generally, “for those without access to arid deserts or continental glaciers, perhaps the best place to do meteorite hunting is in freshly plowed farmer’s fields, especially following a recent rain,” suggests the American Meteor Society.

It’s probably unlikely that you’ll be in a place where a meteorite is just going to leap out at you, or in the immediate vicinity of a known fall. You may try a different approach by looking for micrometeorites, or specks of extraterrestrial dust just a few millimeters or micrometers wide. Amateur scientist Jon Larsen is convinced that these little nuggets of metallic rock blanket our cities, and Popular Science abridged Larsen’s instructions about how to hunt for them. Before you start your sweep with a plastic-swathed magnet, you might also take some cues from the reporters at The Verge, who gave it a try on a New York City rooftop. Scientific American suggests that the ground around a drainpipe might be another fruitful place to look, since flowing water might leave these dense bits behind (the same way a sluice box can help isolate bits of gold in a stream).

If you do come across something eye-catching and larger than dust, NASA recommends collecting it with gloves or tongs, wrapping it in aluminum foil, and storing it in a baggie, possibly nestled against a desiccant packet to help keep things dry. This isn’t to isolate you from anything dangerous on the surface—it’s to protect the maybe-meteorite from humidity and the oil and microbes on your hands. (Just remember: You can’t necessarily steal away with any rock you happen to find. Many swaths of land are protected by federal laws, and visitors aren’t permitted to remove or keep rocks from them.)

Study the outside.

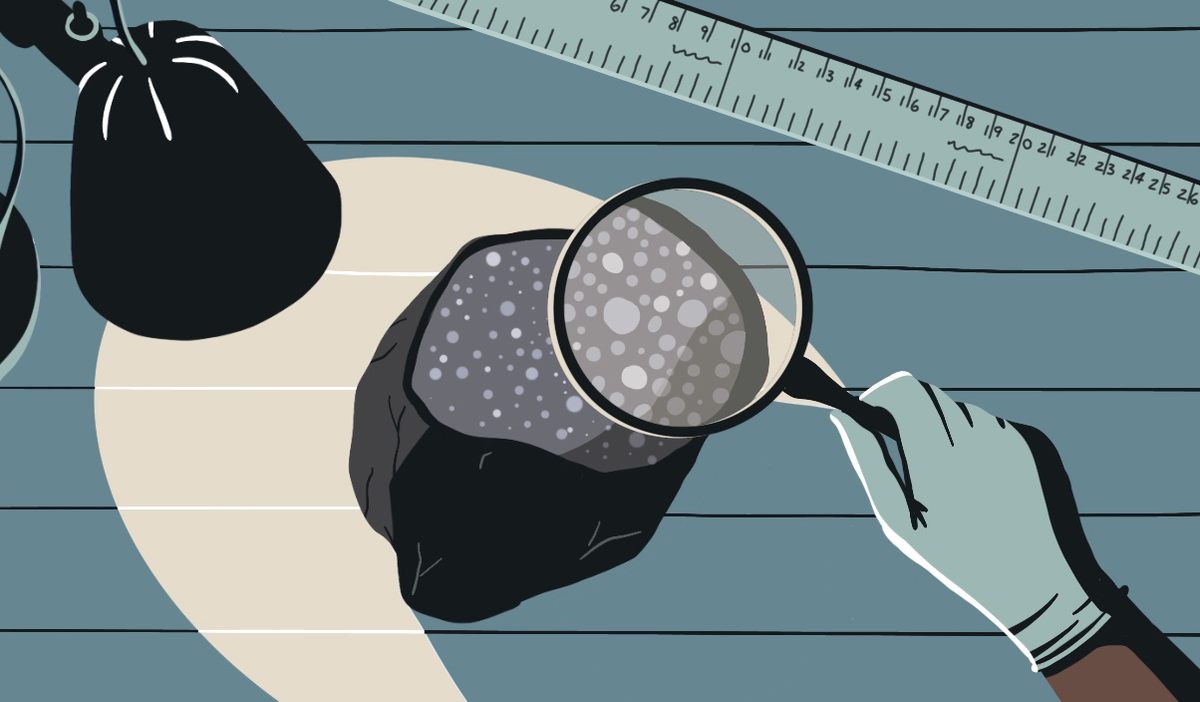

Finding a good candidate for a meteorite is only the beginning. The next thing you need to do is take a close look at the surface. (In the case of micrometeorites, you may need a magnifying glass or microscope.)

Meteorites often have a thin, shiny, black coating, known as a fusion crust. This develops as the rock barrels through the atmosphere, generating enough heat to melt the surface a little. Be careful not to confuse this with desert varnish, a reddish brown coating that grows when clay, iron, manganese, and microbes build up on terrestrial rocks.

Other hallmarks of a meteorite include regmaglypts, or thumbprint shapes in the surface, as though someone had picked up wet clay and pressed a little too hard. (Then again, the longer a rock sits around on Earth, prone to weathering, the more likely it is to lose some of these more subtle signs.) Meteorites tend not to be perfectly round, either—so spherical pebbles aren’t good candidates for further examination.

Take a look inside.

This won’t work for your tiniest samples, but to really get to know a potential meteorite, you’ve got to see inside it. Saw or file off a small chunk. You’re looking for the presence of some things and the absence of others.

There are three main types of meteorites (stony, iron, and stony-iron), and lots of finer distinctions. If you do find a meteorite, it’s most likely to be a stony one, and specifically a chondrite, made up of the oldest debris in the solar system. The insides of chondrites are distinctively freckled with chondrules, little spherical mineral grains. (A cross-section will look a little like a mottled slice of mortadella, with the grains usually smaller than 1/25 of an inch across.) You’ll also find a smattering of shiny metal grains—especially iron and nickel.

But if you see bubbles, you’re probably not looking at a meteorite. These little cavities are known as vesicles, and they generally form in igneous rocks when gas expands as magma cools and hardens, which means they come from a place with volcanic activity—namely, Earth. Yes, both the Moon and Mars once had volcanic activity, but neither place is the source of very many meteorites. Most of the stuff that lands on Earth from space started off as a part of an asteroid. Though vesicles can also form when asteroids collide, this is really unusual. When you hear hoofbeats, expect horses, not zebras. “Bottom line: If you have a vesicular rock, then it’s not a meteorite,” writes lunar geochemist Randy L. Korotev, retired from Washington University in St. Louis. “Such rocks are very common on Earth but are exceedingly rare among meteorites.”

Weigh it.

Meteorites tend to be heftier than other similarly-sized rocks due to their high metal content. Even so, “It’s not enough to say your rock is heavy,” according to the Meteorite Museum at the University of New Mexico. You need to quantify the density, which is mass divided by volume. “Iron meteorites are 3.5 times as heavy as ordinary Earth rocks of the same size, while stony meteorites are about 1.5 times as heavy,” the museum notes. Consult the museum’s meteorite ID guide to see how your rock’s density stacks up against others—and if you’re anywhere near Albuquerque, call ahead to schedule a tour of their collection.

Grab a magnet.

Because chondrites, the most common type of stony meteorite, are rich in iron and nickel, they are magnetic. No need for anything fancy—a cheap, run-of-the-mill drugstore magnet will provide some pull.

Remember: That doesn’t make them magnets themselves. If paper clips or staples stick to your rock, you might have a piece of the mineral magnetite on your hands, instead, as Jim Holstein, collection manager of physical geology at the Field Museum in Chicago, demonstrates in this video.

One more caveat: Some of the rarest meteorites, including achondrites, lunar meteorites, and Martian meteorites, contain very little metal and aren’t magnetic. Since these are all superlatively uncommon, though, there’s probably no need to worry about ever finding one.

It’s tricky to know if your suspected meteorite (or the dust you picked up from the roof) is the real deal. If you’re still stumped, it may help to consult this “meteorite or meteorwrong” flow chart made by researchers at Brazil’s Museo Nacional. (Their wide-ranging collection, badly damaged by a catastrophic fire in 2018, includes the 11,600-pound Bendegó meteorite, discovered in Bahia in 1784. The rock, as you can imagine, survived intact.) For a definitive diagnosis, you might need to enlist the help of a lab that can run a chemical analysis.

Okay, so maybe—probably—you didn’t find something that literally dropped in from somewhere beyond this world. But now you’re a geological investigator and there’s no telling what else you might find out there.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook