It’s Not So Easy to Rename a Species With a Problematic Moniker

One scientist argues that we should reconsider the Bobbit worm.

In 1993, invertebrate zoologist Terry Gosliner found himself with the monumental task of naming a thousand new species of spineless animals as he compiled his latest book, Coral Reef Animals of the Indo-Pacific. It was perhaps an unfortunate coincidence that it was the same year that the trial of a woman who had cut off her husband’s penis after years of abuse made headlines around the world. So when Gosliner came to a menacing predatory worm—bestowed with both a phallic shape and scissor-like jaws—in need of a name, one came to mind: Bobbitt.

That trial 25 years ago was sensationalized and the subject of many a late-night television joke, but the situation that allegedly drove Lorena Gallo (then Bobbitt) to the infamous act was no laughing matter. The recent release of a new documentary, Lorena, which details the domestic and sexual abuse she suffered, has brought renewed attention to the case, and has one scientist campaigning to rename what’s been known as the Bobbit worm (Eunice aphroditois). In theory, it makes perfect sense to change the common name of an animal when the name has grown increasingly problematic with time. In practice, however, it’s a little more complicated.

Kim Martini isn’t a marine biologist—she’s a physical oceanographer—but she had known about the predatory worm in question for quite some time. It’s a little notorious among ocean life enthusiasts for its fierce ambushes, the fact that it can grow up to ten feet long, and a memorably scary appearance in BBC’s Blue Planet II series. “I grew up in a time when Lorena was all over the news,” Martini says. “I never really understood the entire story, and so I used to joke about it.” When she read a 2019 profile of Gallo in The New York Times, Martini immediately made the connection between woman and worm. “In retrospect, it’s totally messed up,” that they should be associated with one another through the name of her abuser, Martini says.

So Martini decided to post a call to rename the worm on the blog Deep Sea News. “Bobbitt is the last name of a rapist and domestic abuser that should not be immortalized anywhere, not the least being scientific literature,” she wrote. At the end of her post, Martini linked to an organization that works to support survivors of domestic violence and suggested an alternative name: the sand striker. “By the time this article is to be published, I will have gone through all posts with the words ‘Bobbitt Worm’[sic] and replace [that] name with Sand Striker, and linking back to this article. I encourage others to do the same,” she continued. (Martini did not come up with “sand striker;” it is a less commonly used name for the same worm.) She emailed her call to every scientist she could find who had published work on the worm. “You can’t just send somebody a link,” she says. “You have to lay out the story as to why it’s wrong.” She received a few responses to her email, all positive. She also reached out to Gosliner, who did not respond.

Gosliner says he saw Martini’s post but decided not to comment because he disagrees that the name carries any offense, as he originally named it as a way to vindicate Gallo, who had been found not guilty at trial. “I think that it’s celebrating that she took matters into her own hands, so to speak, and delivered what some people felt was justice,” he says. “And it’s reflective of the fact that the worm has the ability to deliver this lethal blow.” Gosliner also explains that he chose to spell the worm’s name with just one “t” so it would be less closely linked to the trial, and that the name nods to the worm’s tendency to bob up and down from its burrow. Martini, however, is more concerned with impact than intent. “It’s not [Gallo’s] responsibility to be involved in this,” she says, adding that she didn’t reach out to Gallo in case the subject would be triggering. “That would be putting the onus on the victim.”

Scientifically speaking, Gosliner says “Bobbit” is a more apt name for the creature than Martini’s alternative: “It’s not striking the sand. It’s grasping things.” Martini counters that the name Bobbit is just as biologically imprecise. Sand strikers are polychaete worms, which means they lack external reproductive organs. Rather, they reproduce via the remarkably passive strategy of broadcast fertilization, in which males shoot their sperm into the open water to comingle with the jettisoned eggs of nearby females. Associating them with human reproduction, she suggests, even in a roundabout way, seems to make even less sense.

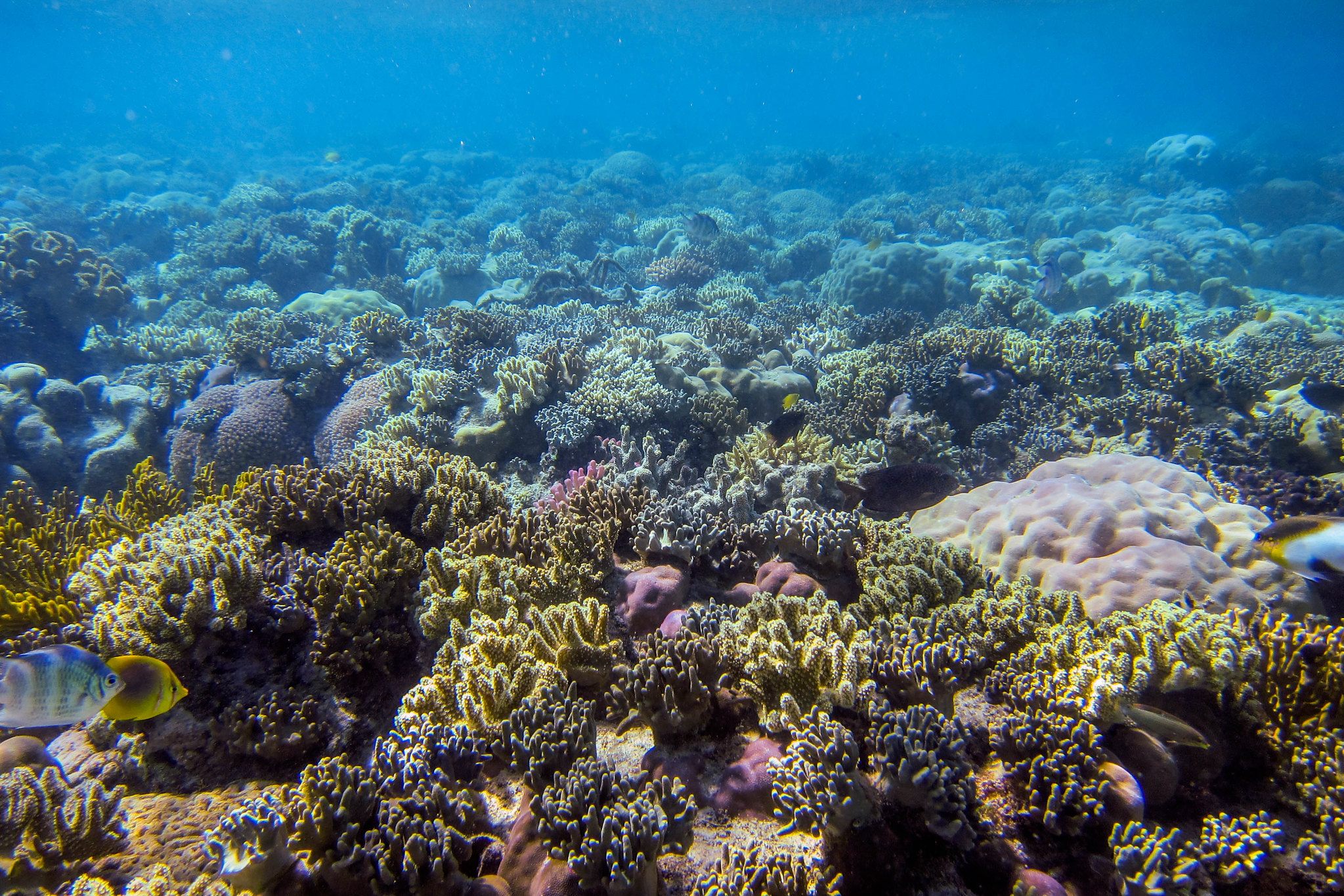

If you’ve ever gone diving in tropical waters, you may have passed over a sand striker or two without knowing it. The worms spend their lives burrowed in the seafloor, their long bodies coiled like a spring, poised to attack. Though their segmented bodies shine with iridescence, they’re exceptionally hard to spot when hidden, which is more or less all the time, with only their five camouflaged antennae poking out. When a fish happens to pass overhead, the striker lunges out and drags its prey down in the blink of an eye, for a death that is no doubt as gruesome as it is sudden.

Gosliner first spotted the species on a research dive in the Philippines, when one erupted from the sand to ambush its prey. It turns out sand strikers are found on almost every Indo-Pacific reef, among some of the highest marine biodiversity anywhere on the planet. The region is home to the Coral Triangle, a kaleidoscopically diverse network of coral reefs on the western periphery of the Pacific: the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Timor-Leste, according to Live Science. The region is so crucial to marine biodiversity that it’s been called the “Amazon of the ocean.” There are, of course, thousands of common names for the creatures that live there, and just about all of them are generally inoffensive.

There’s no official system for renaming species with problematic namesakes, and this is not the first time the matter has been raised. Currently, species receive Latin names when they’re officially identified—using Carl Linnaeus’s system of binomial nomenclature—and some get a common name, though there’s no official system for which ones do. Binomial names are granted under the strict governance of several bodies, including the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and the International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants. As a result, scientific names that are potentially offensive are rather difficult to expunge for reasons beyond taxonomy, according to an op-ed published by writer Melvin Hunter in The Scientist. Consider Talinum caffrum, a succulent found in Africa’s Kalahari Desert. Its name is derived “caffer” or “kaffir,” a racist South African slur. The name remains.

The realm of common names is considerably murkier. Common names can vary from one part of a country to another and sometimes exist only in vernacular, which makes them harder to track and use in a scientific context, according to a post from the University of Florida’s entomology department. Many species, such as E. aphroditois, complicate this even further by having more than one common name. The only way to excise a common name is for everyone to just stop using it, which is a difficult thing to do once people are used to it. For example, the field of horticulture is particularly riddled with offensive common names that stick around. Consider Tradescantia fluminensis, or the wandering jew, or the more incontrovertibly racist common name of Carex secta.

But common names are often non-scientists’ only reference point for certain creatures. They make species identification far more accessible than the official genus and species. In this way, common names are partially responsible for the way we see the world and interpret life around us. A run-in with a Bobbit worm carries a very different connotation than an encounter with a sand striker—though neither sounds particularly pleasant.

Historically (and perhaps unsurprisingly) the most successful efforts to give a species a new common name have been motivated by capitalism, not conservation or anti-racism. Commercial fish companies, for example, successfully rebranded the spiny dogfish and the Patagonian toothfish as rock salmon and Chilean sea bass, respectively, to make them more appealing at the fish counter, according to a post on nomenclature from the University of Miami’s shark research blog.

But there is some precedent for the kind of change that Martini is advocating for. In 2015, Sweden’s Ornithological Society stopped using several common, often internationally used, names for birds in its first Swedish-language guide, according to The Guardian. It banished names such as “Hottentott,” an archaic, derogatory term for the indigenous Khoikhoi people of South Africa, once the name of a species of dabbling duck. The guide changed any bird names that used the Swedish word neger (“negro”) to svart (“black”), and replaced zigenarfågel (gypsy bird) with hoatzin (pheasant).

Martini says she’ll continue emailing her post to anyone she notices using the term “Bobbit” to describe the disgusting, terrifying, strangely beautiful predatory worm. “It’s a small thing that we can change to make right,” she says. “But now we have to change it and move on.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook