The Holiday That Welcomes Back the Sun With Pancakes and Coffee

Around January 25, winter-bound villages in Iceland celebrate the return of the sunlight.

With most of the country just under the Arctic Circle, Iceland does not experience true polar night, where the sun stays below the horizon and darkness lingers throughout the winter.

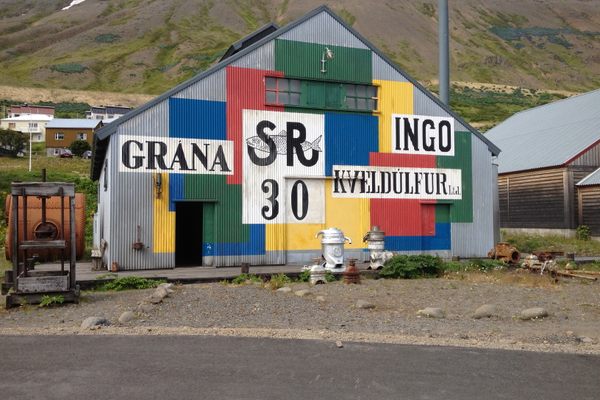

However, some parts of Iceland do experience a version of this phenomenon. Due to the nation’s steep mountains, many people live in areas where the peaks block the sun’s rays. This includes Ísafjörður, a small town in the Westfjords of Iceland. There, from late November to late January, the rays of the sun fail to reach the town, leaving it in shadow.

On January 25 each year, the sun finally arrives at Sólgata, or “Sun Street,” in Ísafjörður. To celebrate, families and friends gather for Sólarkaffi, “Sun coffee,” to welcome the return of the sun.

If it is a cloudy or stormy day, which is not uncommon for Iceland at this time of year, many will postpone the celebration. But even if the sun’s rays can be felt for just a few precious minutes, out comes the strong coffee and Icelandic pancakes, along with wishes of gleðilega sólrisu, or “Merry sunrise!”

Around Iceland, many people celebrate Sólardagur (“Sun Day”) around January 25 with sweets and hot drinks. But in villages such as Ísafjörður, many families choose to have their Sólarkaffi on the exact day that the sun hits their home.

Ásdís Guðmundsdóttir has lived in Ísafjörður for the majority of her life. She can remember celebrating the holiday when she was eight years old, with her mother making pancakes when the sun finally reached town on a clear day. Now, she celebrates with her great-grandchildren, making and eating pancakes the same way she did as a child: with whipped cream and jam.

Icelandic pancakes, pönnukökur, are crepe-like pancakes best served with homemade rhubarb jam and whipped cream. Some people like to cover them in sugar and then roll them up to be eaten like a hot dog. The golden pancakes, with their resemblance to the sun, are eaten to celebrate making it through the darkest days of the year. “We like to call them Sólarpönnukökur (“Sun pancakes”),” says Edda Björk Jónsdóttir, a specialist in education and communication at the Herring Era Museum in Siglufjörður.

In Siglufjörður, a small town surrounded by steep mountains in the north of Iceland, Sólardagur is celebrated on January 28, the day that the sun’s rays shine over the mountaintops and fall on the town.

In addition to celebrations at home, companies in town set aside time for employees to have sun pancakes together. At noon, elementary school children gather on the church steps to sing songs such as “Sól er yfir Fjallabyggð,” an ode celebrating the light reaching the Fjallabyggð region.

These days, most people tend to leave their small fishing villages to move to the capital of Reykjavík, often for employment or education. Yet Sólardagur is such a meaningful day to people from places like Ísafjörður and Siglufjörður that it is also celebrated in Reykjavík, even though the city receives direct sunlight throughout the winter.

Ísfirðingafélagið, founded in 1945, is an organization based in Reykjavík that connects people from Ísafjörður who have moved to the city. Their big event of the year is Sólarkaffi.Since 1946, it has been held annually, except for when the Covid-19 pandemic prevented large gatherings of people.

What began as a small gathering over coffee and pancakes on a Sunday afternoon is now a Friday night event with a ball and dancing—but only after the traditional coffee and pancakes are served, of course. “Even though we moved to Reykjavík and could see the sun all year around, we kept this tradition to celebrate the day of the sun, in honor of our hometown and those who live there and have not seen the sun for a long time,” says Rúnar Örn Rafnsson, the current chairman of Ísfirðingafélagið.

“Pancakes and coffee are a vital part of the celebration,” says composer and pianist Halldór Smárason, who is from Ísafjörður but now lives near Reykjavík. Smárason performs at Sólarkaffi every year, and wouldn’t miss it for the world. “I really love this event as it’s an opportunity to reunite with old friends and familiar faces from my hometown,” he says.

For many people, Sólardagur marks a return to easier times. “The sun makes everyone happier, the grass gets greener, fishing becomes more manageable, and the long-awaited light creates a true and deep feeling of appreciation in all of us,” says Smárason.

The celebration is especially meaningful, considering that the winter darkness can be detrimental to mental health. Thelma Björk Guðmundsdóttir, the head of the mental health team at the hospital in Ísafjörður, notes that the arrival of the sun in dark Icelandic towns is a genuine cause for celebration. “It means a lot to us when it happens, because of how it can affect us to be in darkness for so long,” she says, “which people might not quite understand unless they live with it.”

Jónsdóttir from the Herring Era Museum shares that sentiment. “I think that most people associate hope with the Sólardagur,” she says. “Some people have said that it’s almost like the sun fills you with light, hope, and joy on the inside.”

More than simply coffee and pancakes, Sólardagur and Sólarkaffi are a chance for families and communities to celebrate the first sign of winter’s end, together. “It’s definitely a turning point,” says Jónsdóttir. “We have been without the sun for over two months, and when the sun finally comes back, it means that there will be less darkness.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook